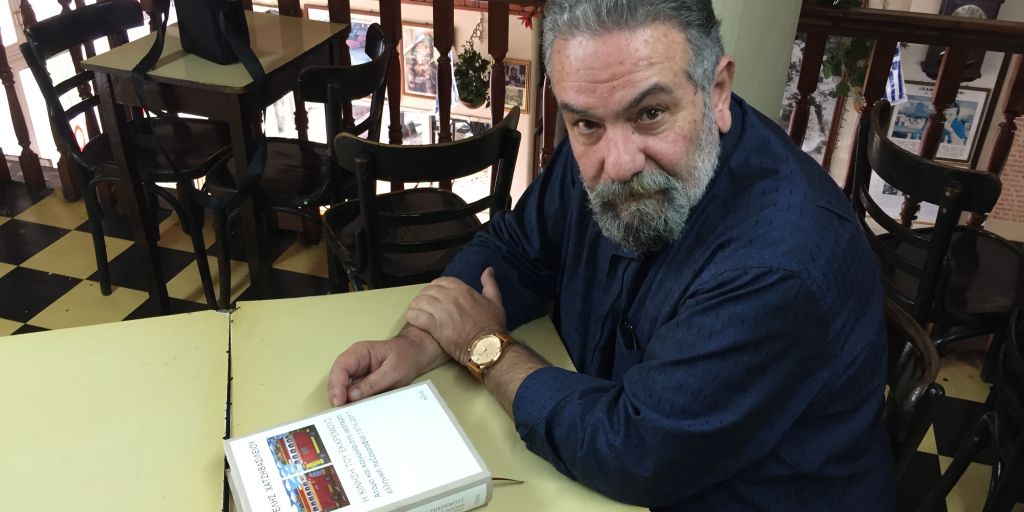

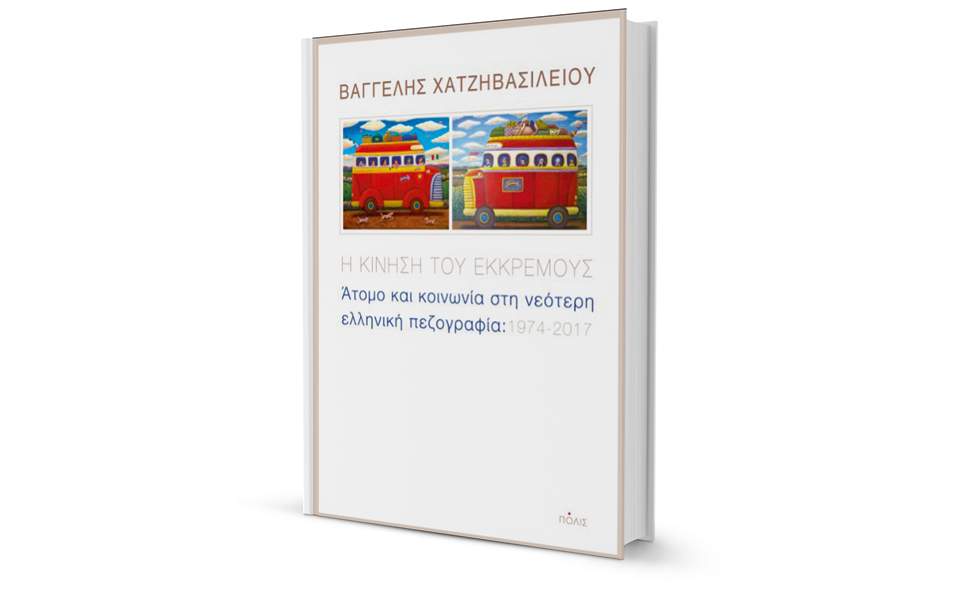

Vangelis Hatzivassileiou was born in Athens in 1959. He studied Political Science and Regional Economics. He cooperated with the newspapers Proti and Kathimerini as well as with various literary magazines, while he worked as a book reviewer for Avgi (1982-1991) and Eleftherotypia (1991-2010). From 1998 to 2009 he was a member of the editorial team of the “Bibliothiki” section of Eleftherotypia. At present, he cooperates as a book reviewer with Vima tis Kyriakis and is a member of the editorial team of the literary magazine O anagnostis. He is also a regular partner of the literary magazines Βοοks’ Journal and Entefktirio and cooperates with the Athens News Agency. His scholarly study titled Η κίνηση του εκκρεμούς: Άτομα και κοινωνία στη νεότερη ελληνική πεζογραφία 1974-2017 [The Move of the Pendulum: Individual and Society in Modern Greek Fiction 1974-2017] was recently published by Polis Editions.

Vangelis Hatzivassileiou spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest writing venture The Move of the Pendulum, a study on Modern Greek fiction that begins in 1974 and extends to the present. He comments on the relationship between the individual and the collective represented in Greek fiction during the period under study, as well as on the major convergences and divergences that are observed in the literary production of the last forty years, noting that “multilateralism is a structural feature of fiction since 1974, and this is exactly where I focus in my book: to show the crossroads and the convergences, but also the variations and heterogeneities of the material available”.

Asked about the special emphasis he lays on the historical novel, he explains that from 1974 onwards, the historical novel “attempts to bravely open up to the Other and the notion of otherness”, to “the heterogeneous cultural identities and their multiple levels of co-existence, contradiction or interdependence”. He concludes that his scholarly study “aspires to act as a historical snapshot: a snapshot which at the same time seeks to move beyond the random, the occasional and the fleeting, recording the literary momentum produced in a specific era”.

Υοur latest writing venture The Move of the Pendulum delves into Modern Greek fiction of the last 45 years (1974-2017). Tell us a few things about the book.

My study on Modern Greek fiction begins in 1974 and extends to the present; yet, in reality, its time span goes beyond this milestone, covering the entire post-war period: my research comprises the post-war generations of writers, who remained intimately connected to the thorny issues of politics and history and produced a significant part of their works from 1974 onwards. The book attempts to answer a fundamental question in my judgment: how is the relationship between the individual and the collective reflected upon fiction written following the regime change in 1974, which radically changed the pre-dictatorial reality of Greek society?

“The course of Greek literature since 1974 is neither inescapable nor one-way: it rather resembles the movement of the pendulum: from society to the individual and from the individual back to society”. How is the relationship between the individual and the collective represented in Greek fiction during the period under study?

Those who began writing immediately after the collapse of the military junta in 1974, hastened to disengage their works from the drama of politics and history and gradually severed ties between the individual and public space. The individual thus loses his identity as a citizen, while his individualism parts ways with his social character. In such a context, these writers will clearly differentiate themselves from the attitudes and choices of their predecessors, when literature was translated into a political act, even if it tried to break free from the suffocation of collective elements, bringing forward instead, in a spirit of opposition and freethinking, the importance of individual identity and independent being.

Freedom, however, in this avant-garde form, will quickly prove, from the early years following the change of regime, an empty word. The individual may have priority now, yet he seems ready to be cast away by his environment, tending to be identified with an immensely discontinuous and meaningless present. It’s the time when History loses its timelessness and comes to be experienced as a history of specific events and special circumstances, while literature moves from the collective to the individual, ready to push the collective aside at the first opportunity. What we are seeing is a rather degenerative version of freedom, which will lay the ground -despite the absence of any endogenous relevance whatsoever- for the parody writers of the 1980s, who by means of the depressing irony of their monstrous world will move to a further downgrading of the individual, confining him into a strictly private space.

In contrast, crime and historical fiction move with passionate force towards the collective, as do to a smaller or larger degree other categories of writers of this specific period. Writers, for instance, who depict everyday social life, will portray various aspects of modern collective co-existence without ignoring its social or historical background. A more intense narrative will be produced in this perspective by socio-political writers who by delving into either deep political waters or shallower ones will mark out deeply rooted economic and social frictions. Writers who act as prophets of the future, constitute quite a significant parameter of literature from 1974 onwards, and will go a step further by illustrating an ominous universe both for the present and the future.

Specific social desiderata would be detected among writers of sci-fi literature, while writers of heterotopias (a substantial and active category) would portray their marginal worlds as places where a person’s vida nuda is merely a socially manipulated and devalued life, trapped by the absence of the political while also confined in an existential suffocation caused by the dark hierarchies whose will remains unknown.

In the book you attempt to interpret the literary co-existence of many, quite distinct generations, which unfolded during the same period, and expressed different aspects of the same collective experience. Which are the major convergences and divergences that are observed in the literary production of the last forty years?

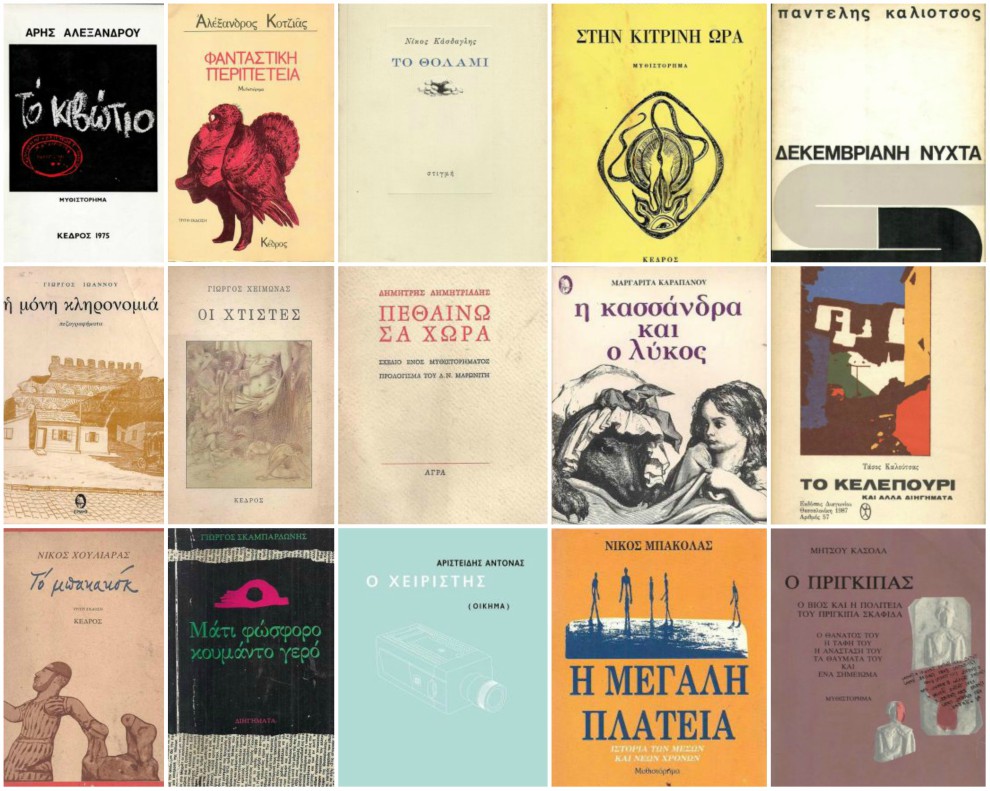

Literature constitutes the prime framework that brings to light the different perspectives developed in a common environment. Yet, literature itself is not characterized just by the different ways the social environment is being perceived, but also by its wide morphological and thematic variety. I would say that this multilateralism is a structural feature of fiction since 1974, and this is exactly where I focus in my book: to show the crossroads and the convergences, but also the variations and heterogeneities of the material available. It wouldn’t be easy to name the major or minor convergences and divergences – and even if we were able to detect them, we wouldn’t avoid a schematic presentation. This wide variety doesn’t allow for the dominance of certain tendencies over others. If we had to delve into something in this respect, it would be the writers’ interest in historical and crime fiction. Both genres have been substantially renewed.

You lay special emphasis on the historical novel, commenting that the renewal of the historical novel inaugurates a turn towards a new collective experience, which will lead to the dominance of the collective in the literature of the crisis. Tell us more.

From 1974 onwards, the historical novel keeps distance from the patriotic triumph and national complacencies that were, to a large degree, its main traits in the 19th and 20th century, attempting bravely to open up to the Other and the notion of otherness. The absence of a coherent self, which was a primary characteristic of a great number of heroes that appeared in the literary production of this period, will find in the historical novel a vital counterbalance: the heterogeneous cultural identities and their multiple levels of co-existence, contradiction or interdependence.

Likewise, although the individual has not moved an inch away from the post-modern fate of his volatility and indefiniteness, and despite having given up on the pursuit of self-efficiency, he nevertheless endeavors to regain citizenship and integrate himself, in line with Herder’s old aphorism, into a network of collective commitments. We should of course clarify the obvious: under such conditions, the collective doesn’t arise from the intense turmoil of politics and History, but through the memories of civilization, scholarship and culture. As for fiction written during the crisis, it is largely a product of specific political and social circumstances: it has no particular relevance to the historical novel and actually constitutes a different chapter.

It has been argued that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

This argument is largely a fable, which no way could be applied to Greek fiction, at least not since the 1930s. In Greece we have indeed a strong tradition in short stories extending to the present, but longer forms (with all the narrative, stylist and technical problems entailed) have long been at the forefront of literary processes; the sheer volume of post-war novels, which rose dramatically since 1974, attests to this. In recent years, Greek prose writers have been following closely international literary trends, mainly focusing on the novel – at least in terms of quantity.

Where does the subjectivity of the book reviewer meet the objectivity of the literary scholar in your writings?

A book review constitutes contemporary appraisal par excellence: what is good and what is bad, what went right and what went wrong, what is important and what isn’t in a literary book. In contrast, scholarly research needs to be skeptical of such reasoning right from the beginning and not get caught up in zealous reactions. A literary scholar should neither condemn nor praise, but rather talk about the conditions under which literary success or failure occurred within the volume of the works he has singled out. Because a literary scholar, unlike a contemporary book reviewer, does not have to recommend to readers what to read without any reservations and what to ignore at any cost, but to indicate to future, and presumably more dispassionate and thoughtful readers, the context (social, cultural and aesthetic) within which literature won or lost the bet.

As for the history of Greek fiction since 1974, I have tried to follow the rules that govern scholarly research, but to what extent have I managed to avoid value judgments as regards my interpretive and historical framework? My research hasn’t dealt with previously classified and ranked material that other researches had already delved into. In such a context, it’s highly unlikely to avoid evaluation, i.e., some kind of appraisal drawn from contemporary book reviews. That is where, after all, the literary canon produced by the present scholarly research is based: a canon that is still unstable as far as older writers are concerned, and a regulatory framework that is constantly adjusted and revised in the case of contemporary ones. In this respect, an impartial catalogue or index is not really the solution.

Τhe only option is to trust your intuition and experience once again – and take the risk of your choices, even though you know that a great part of literary production will most probably stay out of the scholarly research that will be carried out later for the same period. My book constitutes research in the making, one that attempts to offer a historical perspective to its material, while it cannot and doesn’t want to ignore the structure of feeling of its time nor its evaluative basis. It is a writing not addressed to a remote reader, an unknown person in an unforeseeable future, but to a reader who has experienced things also experienced by the critic who became a scholar. I am talking about scholarly work that is not synonymous to philology but which aspires to act as a historical snapshot: a snapshot which at the same time seeks to move beyond the random, the occasional and the fleeting, recording the literary momentum produced in a specific era.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Dimitris Fyssas

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE