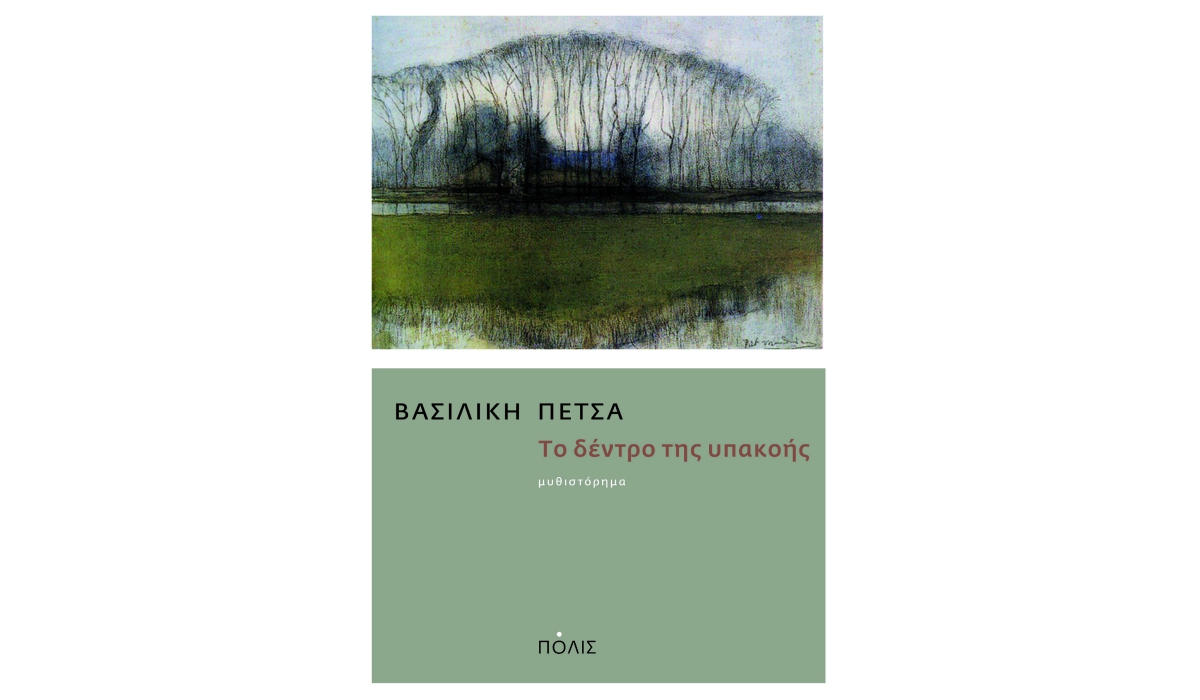

Vasiliki Petsa was born in 1983. She studied Media Culture and Society at the University of Birmingham and European Literature at the University of Oxford, UK. She holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Peloponnese. She has published a novella Thymamai (I Remember, 2011), two collections of short stories Ola ta chamena (All Things Lost, 2012) and Mono to arni (Only the Lamb, 2015), a novel To dentro tis ipakois (Tree of obedience, 2018) and a study based on her Ph.D. thesis Otan grafei to molyvi (Political Violence and Memory in Greek and Italian Literatures, 2016), all from POLIS Publishers.

Vasiliki Petsa spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest novel Tree of Obedience noting that among its themes and motifs are “the relentless pursuit of utopia, the tenacity of religious faith, the resistance to change, the fear and the lure of the unknown“. She explains that “it’s primarily by instinct” that she approaches writing, in the sense of “the reserve stock of knowledge or the acquired taste, configured through ardous consumption of several literary and other cultural texts“, and adds that “creativeness concerns not only the process of writing, but also of reading“.

She comments that the “professionalization of literature certainly entails unequivocal benefits for the author, but it would also incur serious risks” given that one would have to “handle both the iron laws of the (capitalist) market or the personal and financial cost of artistic failure“. She concludes that “global interconnectedness has been intensified in the last few decades“, and that “whether this will lead to greater cultural diversity or to defensive introversion is the million-dollar question – not just in terms of literary production“.

Your latest writing venture Τree of Obedience received quite favorable reviews upon publication. Tell us a few things about the book.

I would have to state, first of all, that for the Tree of Obedience to be crystallized into an adequately coherent and yet curiously disconnected composite and intricately meaningful structure in my mind, at least one year was required, to the effect that it would be nearly impossible for me to provide an all-inclusive summary of the plot – in the opposite case, it would also mean that I have failed in my venture of inconclusive answers and parallel strings. Themes and motifs is, fortunately, all I could provide: the relentless pursuit of utopia, the tenacity of religious faith, the resistance to change, the fear and the lure of the unknown. The latter also applies to the authorial circumstance, having had to tackle the exigencies of a novel and abandon the safety of the short stories, to which I was previously accustomed.

“When you write, you have to define your own distinct writing style […] The structure should of course be solid and functional, but it should also be beautiful”. What role does language play in your writings?

Without being able to define the particularities of literary discourse −several criteria have, of course, been set throughout the years, but they pertain to the critical and analytical functions, i.e., they are applied, not without being contested, to the end-product of writing−, I would maintain that it is primarily by instinct that I approach writing; in other words, this is how I chose my words. With the term ‘ instinct’, mind you, I don’t purpose to invoke any kind of metaphysical talent, no – rather, I refer to the reserve stock of knowledge or to the acquired taste, configured through arduous consumption of several literary and other cultural texts, as well as everyday language, which is automatically activated when one puts oneself down to writing, while also keeping in mind the specificities of the

Giorgos Perantonakis argues that “in recent years, many Greek novels, following a similar trend in Europe and the USA, are modular, fragmented and multi-dimensional” and that it’s up to the reader “to follow and connect all those incongruous elements”. Would you like to comment?

I would be at least hesitant to comment on this particular argument, as, by doing so, I would need to imply that I am thoroughly familiar with the totality of Greek, British and US literary productions (which I am certainly not). If such authorial strategy can indeed be identified as a visible trend, I would be more than honored to be included in it, whether intentionally or not. It would mean that, irrespective of how we approach literature itself, authors address readers as (almost) equals, patronizing them as little as possible and acknowledging that creativeness concerns not only the process of writing, but also of reading.

It has been noted that Greek writers have a preference for short form and that short story collections have outweighed novels and longer narratives. How would you comment on this?

Again, one would need to be aware of specific figures pertaining to the Greek publishing industry if they were not to reiterate conventional wisdom and half-baked truth. The question whether major novels can be written in Greece, given all sorts of different historical, social and cultural factors, leaves me rather unconvinced, both in principle and in practice, as in my all-time favorite novels’ list figure prominently many Greek ones. However, leaving personal taste aside, I have the impression – and this is just an impression – that short stories are more convenient −although not at all easier− to write if you cannot make a living out of writing literature, which, sadly or not, is the case for the majority of Greek writers, which also leads us on to your next question.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. Would you agree that in a country stricken by the crisis, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

It certainly is and if I am not terribly mistaken it has always been so, crisis or not (we cannot blame everything on the crisis, as if it were some kind of Boogeyman, whose sudden appearance overturned blissful normality). In my previous answer, I added the phrase “sadly or not”: the professionalization of literature (and by this I do not intend to imply that writing literature “as a leisure time activity” means that it is taken lightly by default) certainly entails unequivocal benefits for the author, but it would also incur serious risks: I, for one, could not, and would not be willing to, handle both the iron laws of the (capitalist) market or the personal and financial cost of artistic failure.

It has been argued that the new generation of Greek writers is multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational. How do they relate to world literature? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

In a sense, Greek literature has always been, to varying degrees, multicultural, multiethnic and multigenerational, either we focus strictly on the literary field, and take into account translations and first-hand language access to original works, or if we refer to the socio-cultural context within which Greek literature had been produced. It certainly is the case, though, that global interconnectedness has been intensified in the last few decades: whether this will lead to greater cultural diversity or to defensive introversion is the million-dollar question – not just in terms of literary production.

* Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE