Vassilis Lambropoulos has been C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek and Director of the Modern Greek Program at the University of Michigan since 1999, teaching in the Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature. Before that, he was Professor of Modern Greek at the Ohio State University for eighteen years. Among his former graduate students are two generations of today’s faculty promoting Modern Greek across the United States and beyond, including Giorgos Anagnostou (Ohio State University), Eric Ball (State University of New York), Vangelis Calotychos (Brown), Etienne Charriere (Ankara University), Maria Hadjipolykarpou (Columbia), Asli Igsiz (New York University), Konstantia Kapetangianni (North Texas), Neovi Karakatsanis (Indiana), Gerasimus Katsan (City University of New York), Martha Klironomos (San Francisco State), Eva Konstantellou (Lesley) and Yona Stamatis (Illinois).

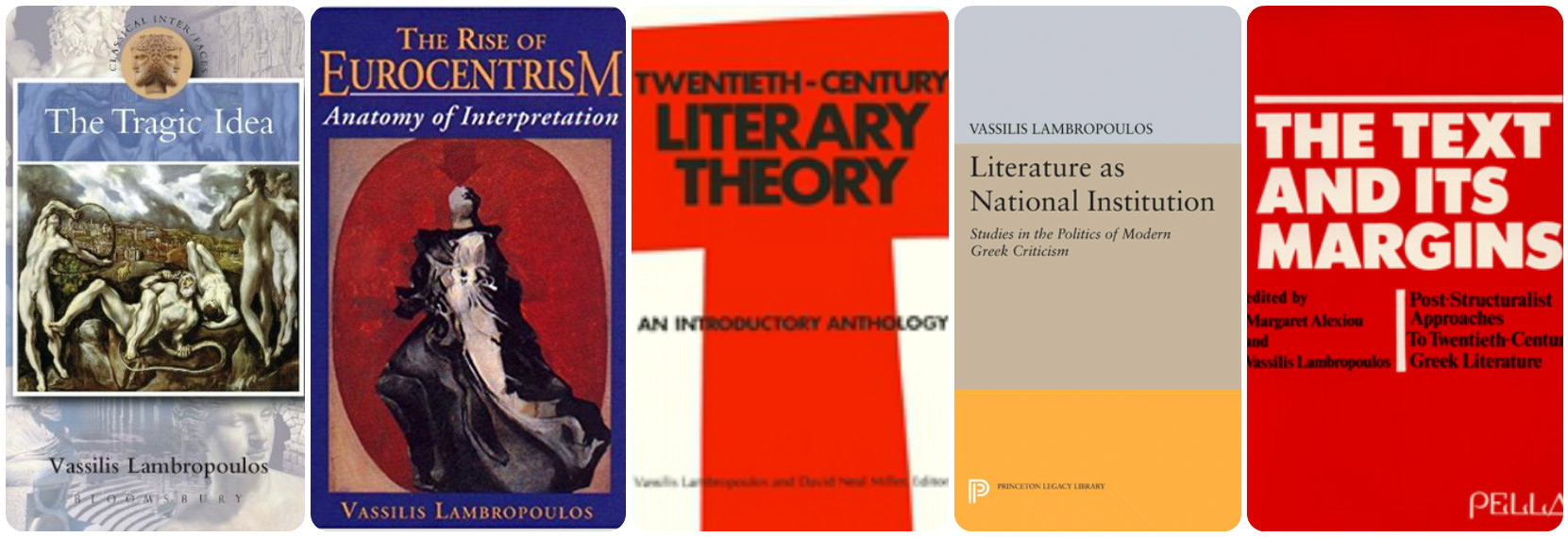

A native of Athens, Lambropoulos received his B.A. from the University of Athens and his Ph.D. from the University of Thessaloniki. He has been teaching courses in Modern Greek language, literature, criticism, and culture, as well as literary theory and comparative literature. His main research interests are modern Greek culture; classical reception and the classic; civic ethics and democratic politics; tragedy and the tragic; word/poetry and music. His books are Literature as National Institution (1988), The Rise of Eurocentrism (1993), and The Tragic Idea (1996). He has co edited the volumes The Text and Its Margins (1985) and Twentieth-Century Literary Theory (1987) and two special issues of academic journals on “The Humanities as Social Technology” (1990) and “Ethical Politics” (1996). He has also published papers, articles, reviews, and translations in journals, periodicals, and newspapers. He is currently writing a book on the idea of revolution as hubris in modern tragedy. He blogs regularly on music, literature, friends, and resistance at https://poetrypiano.wordpress.com

Vassilis Lambropoulos spoke to Reading Greece* about his main areas of research during his thirty-six year academic career as a Professor of Modern Greek, as well as about his most recent work in progress, “a study of some thirty modern tragedies from several countries spanning the eighteenth to the twenty-first century, which dramatize revolution as an emancipatory yet ultimately self-destructive project”.

He notes that “literature does not exist as such, it happens in collaborative spaces and across historical times”, and comments on the term “left melancholy”, which he uses to characterize the Greek poets of the 2000s. He explains that “poetry seems to capture the general crisis exceptionally well because it has itself gone very creatively through an immanent crisis”, and adds that “the new Greek poetry is distinguished not only by its broad, multi-lingual cultural learning but also by the superior university training and theoretical sophistication of its writers”. He concludes that “modern Greek literary studies remains an introverted and solipsistic field which keeps sole possession of its subject and is not interested in conversing with other scholars and critics, let alone sharing it with them. Without an extroverted, comparative, and up to date literary study to support them, new translations will join earlier ones in quick, permanent obscurity”.

For thirty-six years now, you have been a Professor of Modern Greek in the US. What were your main areas of research during your academic career?

I have been a Professor of Modern Greek in the U.S. for thirty-six years, the first eighteen at the Ohio State University and the rest at the University Michigan as the first C. P. Cavafy Professor. I have been teaching and writing in four major areas. a) The literary canon and its margins: I explore forces which control what is promoted, reviewed, admired, taught as important literature, and what is deemed inferior. b) Western Hellenism: Since, as a Greek, I am a figment of the European imagination, I am fascinated by what scholarship, thought, and culture define as superior or false Greek. c) Autonomist politics: I am interested in questions of radical governmentality, such as self-institution and the tragic antinomies of constituted society, that is, how we can be free and at the same time rule ourselves. d) Modern Western music: I study why, more than any other art, music has been the domain where major cultural matters have been tried out and negotiated. Since 2014, I have been combining these four research interests in a blog on poetry, politics, friendship, and music: https://poetrypiano.wordpress.com

What could you tell us about your latest work in progress Revolution as Hubris in Modern Tragedy?

This is a study of some thirty modern tragedies from several countries spanning the eighteenth to the twenty-first century, which dramatize revolution as an emancipatory yet ultimately self-destructive project. I argue that modern tragedy has as one of its central topics the ethical and political dilemmas of rebellion, namely, periods of revolutionary founding when a new polity is caught between limitless self-authorization and self-limiting rule. Tragedy stages the drama of the Greek arche in its double meaning of beginning and rule, and asks whether self-rule may control itself. It explores the inherent contradiction of auto-nomia captured in its very etymology: Can freedom and rule co-exist? In order to experiment with both format and ideas, for the time being I am working on this project not as a book but as a blog-in-progress, which will be published in August: https://tragedy-of-revolution.complit.lsa.umich.edu/

Υοu seem to approach the world of literature with an interest to restore the socio-political dimension of its interpretation. Is this a unifying thread of your work?

You put it very well. In addition to the text, literature has many other integral components and dimensions, such as its production, circulation, reception, consumption, and appropriation. Literature excompasses all of them, and we need to study them whether we are discussing the multilingual manuscripts of Solomos, the private editions of Cavafy, the illustrated books of Dimitris Kalokyris, the installations of Phoebe Giannisi, the collaborations of Katerina Eliopoulou, or the performances of Patricia Kolaiti. Literature does not exist as such, it happens in collaborative spaces and across historical times.

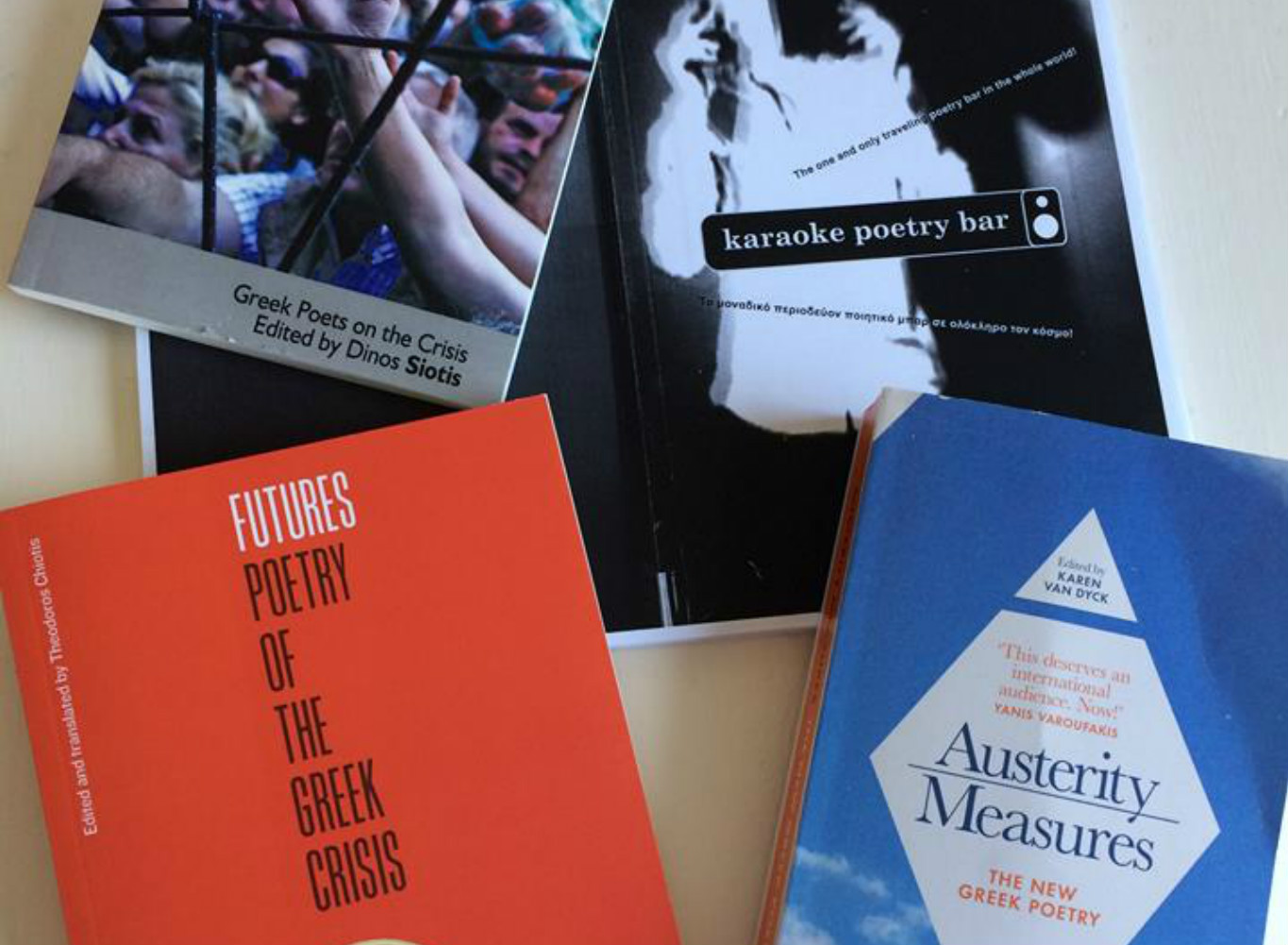

You have commented that “the Greek poets of the 2000s, the Generation of the Left Melancholy, have a strong civic awareness and are very interested in the public presentation of their work. To them, poetry making does not end with writing verses but extends to the domain of their circulation broadly understood”. Could you elaborate on the “left melancholy” term and its various connotations?

The melancholic individual cannot overcome the loss of his favorite person/ideal/object by mourning it, therefore keeps longing for it and reliving it. He internalizes the lost object as a way of refusing to let the loss go. The bankruptcy of the revolution, along with the exhaustion of post-colonial emancipation, have inspired in Greek poets a combination of resignation and resilience which I have been calling “left melancholy.” With their sophisticated skills of composition and performance, the poets of 2000 practice left melancholy as a technique of reflective engagement. Involved as they are in their collaborative and collective poetry/music making, these poets, most of them born around 1980, do not need the consolation of affective attachments which people born twenty or more years before them seek in order to sustain their cruel optimism for the Greek left government.

They never anticipated a left rule as a survival mechanism in their “damaged” world in the first place. Long before the “crisis” exploded, they saw it coming and reflected on it. Living under the devastating economic deprivation that followed so rapidly the 2004 Athens Olympics, the new poets have learned to look at the ancient ruins through the ruins of the neoliberal order. They do not envision liberation or advocate rebellion. They anticipate that the next revolt will explode suddenly, dissipate fast, yet also leave its mark. In the meantime, they are working together with their fellow countrypersons towards bottom-up communities of solidarity, towards a common of sharing, founding, building, even diasporic living. The exemplary collaborative and public work on left melancholy of the Greek Poetry of 2000 shows that the ethics of this political disposition may be driven by refusal, not resignation; defiance, not defeat; rage, not retreat.

Of all the Greek arts, poetry has been identified as the most representative of the current national crisis. Yet, you argue that to speak of “poetry of the crisis” can be misleading given that a crisis of poetry preceded the “poetry of the crisis”. How did Greek poetry manage to move from its artistic crisis of the 1990s to its ‘secessionist autonomism’ of the 2000s and beyond?

The literary generation of the 1990s sank without trace, as poetry underwent a fundamental crisis of civic confidence: for the first time in its modern history, it lost its faith both in its social mission and in emancipation. This was due to the collapse of the left utopia together with the Berlin Wall and to the pervasive narrativization of public discourse, which turned all storytelling into testimony. Following the exhaustion of political utopia and the rise of the traumatized self, Greek poetry felt ideologically and culturally marginalized.

In response to the decline of literary and political grand narratives, a new collective project emerged early in this century: the poetry of left melancholy of 2000. Poets de-territorialized the main milieu of literature by designing provisional zones in its peripheries. For example, they began operating in terrains like the bar, the gallery, and the bookstore. In the realm of mood, they introduced critical attitudes of autonomous disengagement, such as left melancholy, which arrived officially with the 1st Athens Biennale, “Destroy Athens” (2007). When poets realized that certain artists preferred to mourn over the classical ruins, they seceded from the mainstream milieu by establishing their autonomous terrain within the Biennale where they collaborated with other artists to create “nomadic art.” In general, because the crisis of left culture preceded that of left politics, poets were able to anticipate not only the “coming insurrection” of Athens in December 2008 but also the ensuing crisis and the self-implosion of the left in 2015.Today poetry seems to capture the general crisis exceptionally well because it has itself gone very creatively through an immanent crisis.

Modern Greek poets have quite different attitudes toward the Greek visual arts and to music. How is this overwhelmingly visual conception of the world that Greek poets have to be explained?

Greeks tend to be more ofthalmocentric that otocentric, that is, they prefer to see than to hear. They enjoy landscapes, not soundscapes. Listening enthuses them but it also confuses and disorients them. Through sight, they feel united with nature, where all is visible, identifiable, and self-contained; nothing moves, nothing happens. In nature, physics constitutes metaphysics, view grants vision. Greek poets, in particular, used to have an overwhelmingly visual conception of the world. Even when experimenting, they pursued a visualist expression, which might be realistic, symbolic, surreal or other but ultimately was based on a Cratylist understanding of language where word, image, and world become one.

Writers did not discuss music with composers because Greek poetry is iconolatric and pursues a total presence, whereas music cannot provide this comfort since it is never fully present and is always in need of actualization. Composers do not work with images, illustrate words, or imitate reality. As a result, their sonatas, symphonies, and quartets were alien to writers, for whom there were only two kinds of music: pieces drawing directly on demotic/popular dances or mimetic settings of poetry – ideally, a combination of the two. This phenomenon has been changing dramatically with the new poetry, because many of its writers are excellent musicians too and many others have impressive musical sophistication. It is exhilarating to see, for the first time in the history of modern Greek literature, poets and composers conversing and collaborating for reasons other than just illustrating verses with music.

Recently there has been an international interest in Greek poetry, as the growing number of translations, poetry anthologies, special sections or individual selections show. Yet, you argue, that this broad dissemination, is treated unsurprisingly in Greece (only!) with (at best) silence or (at worst) scorn. How would you comment on that?

The new Greek poetry is distinguished not only by its broad, multi-lingual cultural learning but also by the superior university training and theoretical sophistication of its writers. Unlike their predecessors, its members do not work on personal confession and national commemoration. Instead, they explore philosophical issues from aesthetic, ethical, political, legal, medical, economic, and other angles. To put it metaphorically, they have been schooled in post-colonialism, post-Marxism, accelerationism, genealogy, deconstruction, queer studies, and similar approaches –– and this theoretical awareness has created a big gap: Greek critics do not know these schools, and Greek scholars detest them, and as a result neither group can handle the new poetry, which is steeped in them. The extraordinary result is that, in response to the silence greeting them, poets have taken their critical reception in their own hands, and review each other’s work regularly and ingenuously, thus extending their creative range. In fact, this is how theoretical reflection has finally made it into Greek literary thought, from performance studies to digital humanities and from translation theory to autonomist politics.

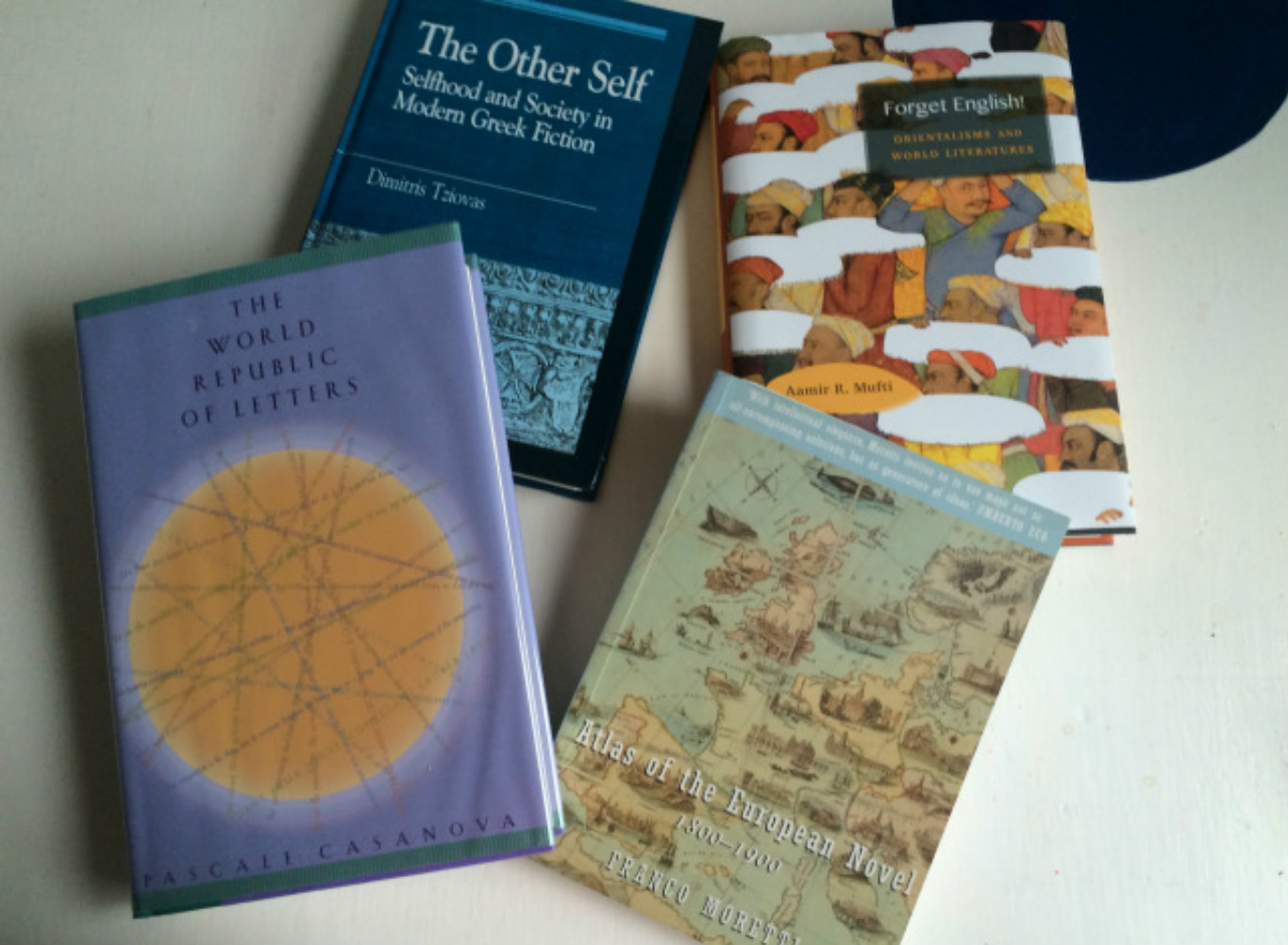

You have argued that Greek writers who live in Greece play no role in the so-called “world republic of letters”, noting that no Greek author or trend is included in textbooks andsurveys of, say, Romanticism or the Avant-Garde, feminism or post colonialism, the ballad or the short story. Yet a promising development is that in recent years Greek poets and novelists have been circulating all over the world. Is there a way for the challenges of integrating Greek literature in the international field to be met? What is the role of Modern Greek Studies in this respect?

Greek writers have not been citizens of the “world republic of letters” because their work is absent from its conversations and references. Translation in itself, indispensable as it is, means very little unless a work subsequently circulates in reviews, essays, studies, and textbooks. Many Greek writers have been translated to some reasonable extent yet they have not attracted any systematic interest from the opinion-making elite, and therefore have not entered any literary histories, surveys, or anthologies, and have gone quickly out of print. The reason is simple: modern Greek literary studies remains an introverted and solipsistic field which keeps sole possession of its subject and is not interested in conversing with other scholars and critics, let alone sharing it with them.

Without an extroverted, comparative, and up to date literary study to support them, new translations will join earlier ones in quick, permanent obscurity. Cavafy is the single exception precisely because critics and scholars (as well as artists and other creators) have been engaging actively with his work, building a large body of thought, research, and art with it. Like him, alien writers are admitted to the “republic of letters” when some of its most distinguished citizens make their translated works part of their everyday conversation and required learning.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE