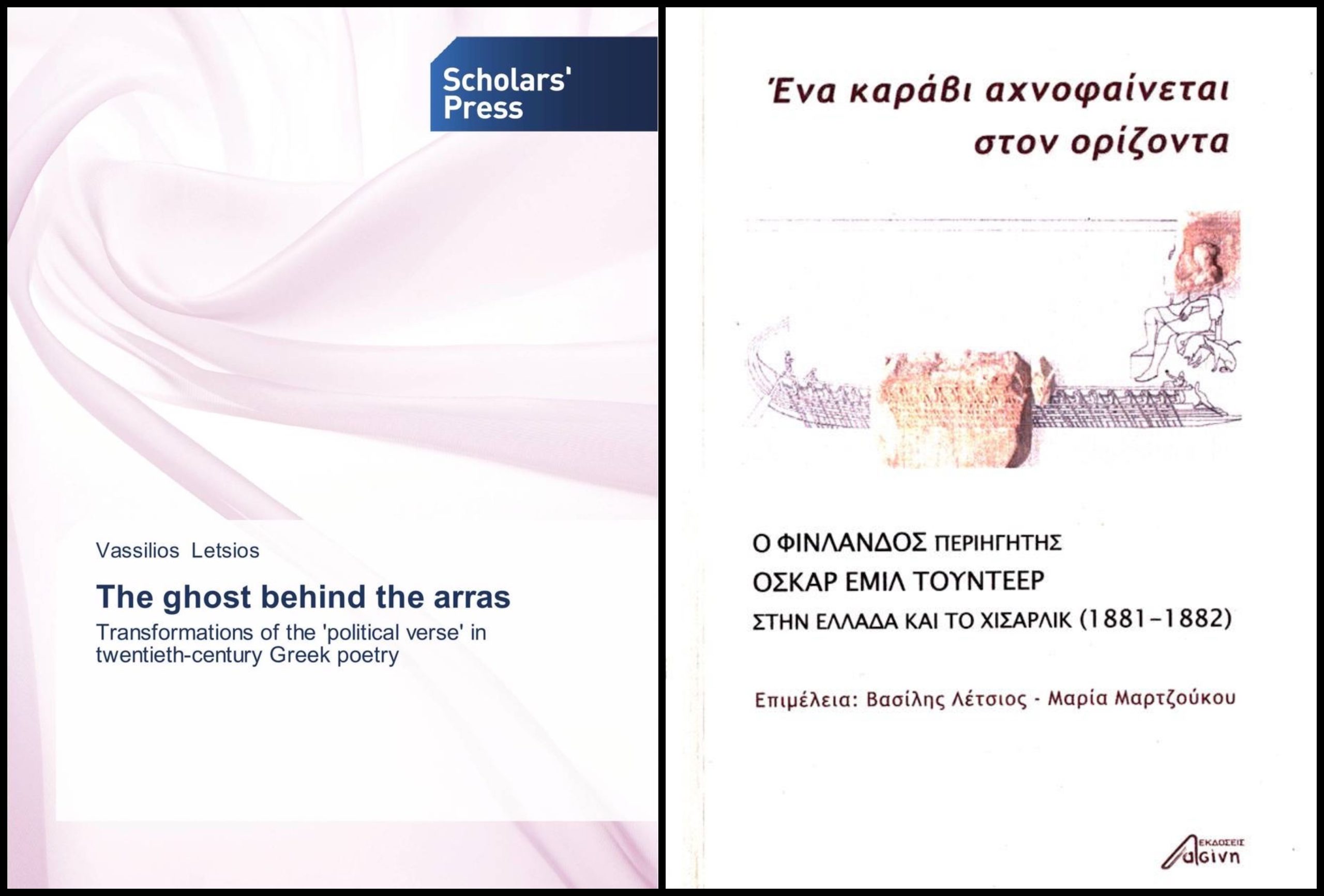

Vassilis Letsios (Lefkada, 1971) is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting of the Ionian University on Modern Greek Literature and Literary Translation into Greek. He studied at the Philology Department of the University of Ioannina (1994) and holds an MA in Modern Greek Studies (1997) and a PhD in Modern Greek Literature (2003) from the Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies Department of King’s College, London University. He has published the monograph The Ghost Behind the Arras: transformations of the “political verse” in twentieth-century Greek poetry (Scholars’ Press, 2013), and he co-edited a study on travel writing entitled A Ship Gleaming on the Horizon. Finnish traveller Oskar Emil Tudeer in Greece and Hisarlik (1881-1882) (Asini Publishing, 2017) (in Greek).

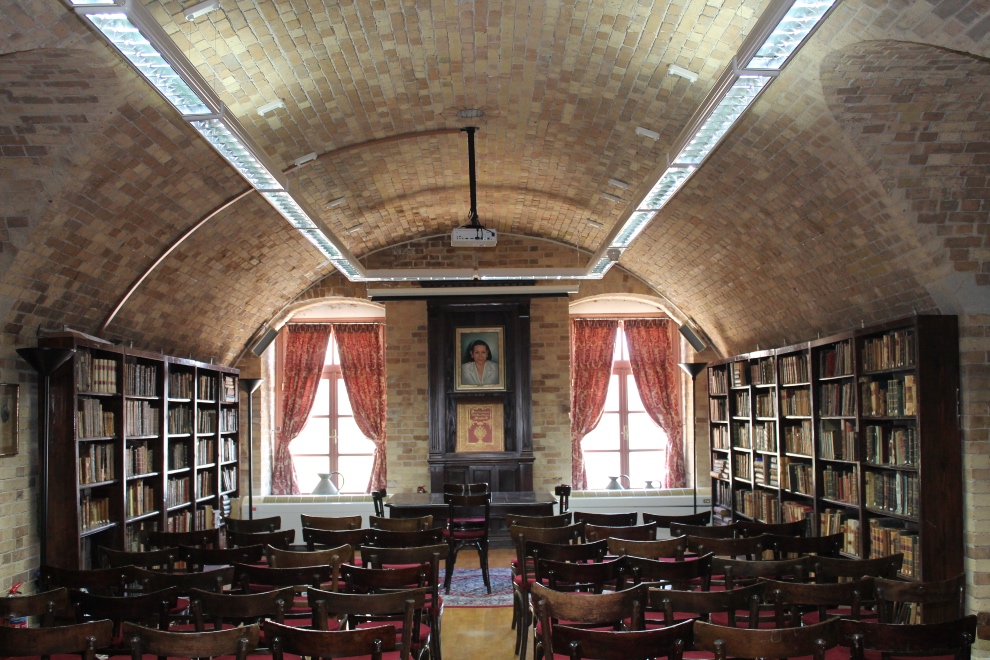

His most recent articles/papers include: Takis Papatsonis as a translator (Frear, 2018) and his relationship with Edgar Allan Poe (T. K. Papatsonis. His critical and essay works, edited by S. Zoumboulakis, National Library of Greece, 2019) (in Greek), Filippos D. Drakontaeidis as a translator of Montaigne and Rabelais (Porfyras, 2018), the translation of Gerusalemme Liberata by Typaldos (The Athens Review of Books, 2019) and the most recent literary work of Christos Chrissopoulos, Sophia Nikolaidou, Panos Karnezis and Ersi Sotiropoulos (Encounters in Greek and Irish Literature. Creativity, Translations and Critical Perspectives, ed. P. Nikolaou, 2020). He is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Public Central Historical Library of Corfu since 2015 and President of the ‘Laboratory for the Translation of Greek Literature’ of the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and interpreting since 2020. He is currently working on a second monograph on the Heptanesian School (in Greek).

Vassilis Letsios spoke to Reading Greece* about his monograph on the Heptanesian School, discussing the strong impact it had on the development of Modern Greek language and literature, while he also comments on the tradition of the political verse and its importance in the shaping of twentieth-century Greek poetics. He refers to the initiatives undertaken by the Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting, which foster a conversation of Greek literature and culture with its foreign partners worldwide, and discusses the main challenges researchers in Greece are faced with nowadays.

Your second monograph, related to the Heptanesian School, is underway. Tell us a few things about the book.

I am really excited about this research field; the primary material is both quite extensive and important opening up, in my opinion, new paths for further research. My aim is to present and explain the translation work carried out by Heptanesian scholars and writers especially of the 19th and the first part of the 20th century, which constitutes a turning point for the Ionian Islands, namely their becoming part of the Kingdom of Greece (1864). This research brings forward a number of important issues related not only to the introduction of important writers, works and literary trends into the Greek language but also with quite uncertain, at the time, and thus crucial issues referring to the formation of the Greek literary/national language, while raising questions of identity and adaptation of an old and established center of Greek Letters, which in the post-Unity era acquired ‘periphery’ traits etc.

Do you agree with those who argue that the linguistic theory and literary practice of the Heptanesian School have had a strong impact on the development of Modern Greek language and literature? Could you elaborate on this influence?

The Heptanesian scholars, writers and artists (friendships and thus influences were quite frequent, if we consider, for instance, the case of Solomos and Chalikiopoulos -Mantzaros in music) quite often shared identical or similar opinions or attitudes vis-à-vis language, literature and arts, and as well as a common conviction for unity and thus continuity. Obviously nothing would have been the same in case the Greek Letters lacked Solomos; his vision for a national language and literature became a point of reference in the world of letters and arts for many years to come. Yet, we should also consider the strength of his partners, who would work for the Greek Letters in an idealistic mood. For the Heptanesians, the struggle for language was above all a political act; a whole system of political and social values dictated their immersion in writing, translation, literary and critical texts, their editing, their philological essays and lectures etc. This system of values that resonated in language and literature was identified by scholars of the Athenian center, such as Kostis Palamas, in whose critical discourse on the Heptanesian Letters one can easily detect a willingness to create a national literary school that would include them.

What about your first monograph related to the transformations of the “political verse” in twentieth-century Greek poetry? Tell us a few things about the tradition of the political verse and its importance in the shaping of twentieth-century Greek poetics.

In this study I tried to delve into the rhythms the free-verse Greek poetry of the 20th century is made of and I came to realize that in many poems written by major Greek poets which appear as free-verse, there hides the national verse, that is the iambic 15-syllable ‘political verse’, like ‘the ghost behind the arras’. This method provides some answers to serious questions as to ‘how poetry is written’ or ‘the relation of form and meaning’ or ‘what the free verse is made of’. One of the major arguments is that the ‘political verse’ continues to exert a great influence on the Greek poetry of the 20th century, although in an latent form. Within this framework, major innovations of form and content started with Cavafy, followed by the poets of the Generation of the 1930s, both before (Seferis, Embiricos, Elytis) and after (Gatsos, Elytis, Ritsos, Seferis, Embiricos) the war, while younger poets would adopt quite interesting techniques (Sachtouris, Mastoraki, Ganas). “No verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job”, as Eliot eloquently put it.

The Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting where you are based, seems to actively pursue initiatives related to the formation of networks and synergies among universities, state structures and private bodies. How could these initiatives foster a conversation of Greek literature and culture with its foreign partners worldwide and thus contribute to increasing their visibility beyond national borders?

The Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting of the Ionian University continues a well established in the Ionian Islands strong presence of translation, as I already mentioned. More specifically, literary translation from and to Greek constitutes an important part of the curriculum at all levels (undergraduate, post-graduate, doctoral), as well as of the initiatives undertaken by very good colleagues, who translate and study/teach translation issues. The Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting tries to be in close contact to the Departments of Modern Greek Studies abroad, both within and outside the framework of translation. In any case, it’s a field we are interested to invest more in the future. Let me take the chance to mention that in the Department there is a ‘Laboratory for the Translation of Greek Literature’ I am the director, and our aim is to establish a strengthened programme of actions that will bring us closer to all those working diligently, both inside and outside Greece, for the translation of Greek literature. Translation studies around the world have earned significant ground, while this field is gradually acquiring the place it deserves in philological/cultural studies. Thus, cognitively, I would say it is an ideal chance for more extroversion and communication, as long as governments are not opposed to it.

What about the main challenges researchers in Greece are faced with? Has the relocation of the National Library of Greece at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center and its transition into a new digital era of innovation and extroversion facilitated research work?

I reckon that the new glowing National Library carries a symbolic value for a number of reasons, among which the modernization of the reading and study space/mentality. Knowledge is open to everyone, while digitalization definitely opens up new horizons for open minds. I am not one of the young researchers given that when I started studying and writing there were no computers and indexing was made by hand. On the other hand, some of my most favorite studies belong to an older era, where there was much more devotion and zest for scientific fields like mine. A modern researcher may find the existing know-how as to material search quite helpful; yet, I consider that an in-depth writing and analysis often go hand in hand with the present era that allows more things to happen more quickly, more superficially and less elegantly. A modern researcher of language and literature is more likely to open up to other scientific fields and attempt correlations; he/she will definitely approach a literary work as a work of culture and will study it as such. Recent research at least vis-à-vis Modern Greek studies has progressed due to a more open approach of Greek issues, despite the fact that the field is shrinking as to working positions. The greatest challenge for a young researcher is not just to enter, but also to remain in the field, given that cultural issues, as we all agree, are every year less and less subsidized.

@Public Central Historical Library of Corfu

@Public Central Historical Library of Corfu

It has been argued that Greek writers who live in Greece play no role in the so-called “world republic of letters”, noting that no Greek author or trend is included in textbooks and surveys of, say, Romanticism or the Avant-Garde, feminism or post colonialism, the ballad or the short story. Yet a promising development is that in recent years Greek poets and novelists have been circulating all over the world. Is there a way for the challenges of integrating Greek literature in the international field to be met?

I remain skeptical about this argument made by Vassilis Lambropoulos. In the prototype, ‘la république mondiale des lettres’ refers to a book where the writer Pascale Casanova, in her attempt to describe the nature of world literature and the structure of the literary world, supports that in order for writers from peripheral countries and languages to achieve worldwide recognition, they should first be accepted by the literary world of Paris. I am not sure whether there exist contemporary or recent writers coming from big or small countries that have ensured, and for how long, a position in this global ‘republic’ (or in a similar one). Yet, I reckon that modern Greek literary trends, to which Lambropoulos refers in his article, have indeed shown a significant mobility (academic, publishing etc) and only time will show which writers and which titles will exert influence on contemporary and future generations, inside and outside the country. International awards, translations, academic research and a public dialogue among contemporary and recent writers is definitely something positive; If, though, anyone knows the contemporary ‘Paris’ of ‘world’ (if there actually exists) letters, let him/her be kind enough as to name it. There may be contemporary writers, irrespective of a country of origin, that they would like to ignore or negate it, and we cannot but respect it.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE