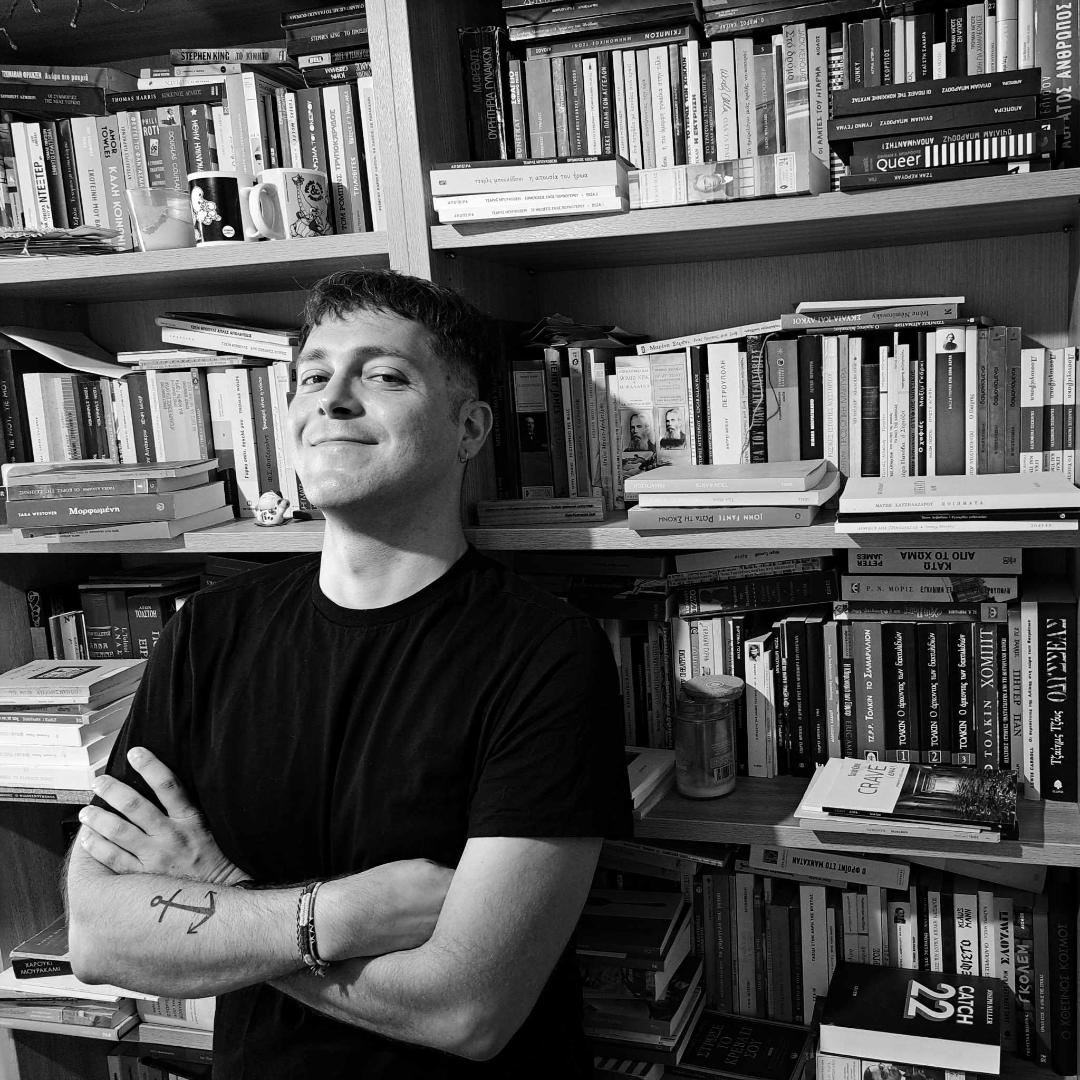

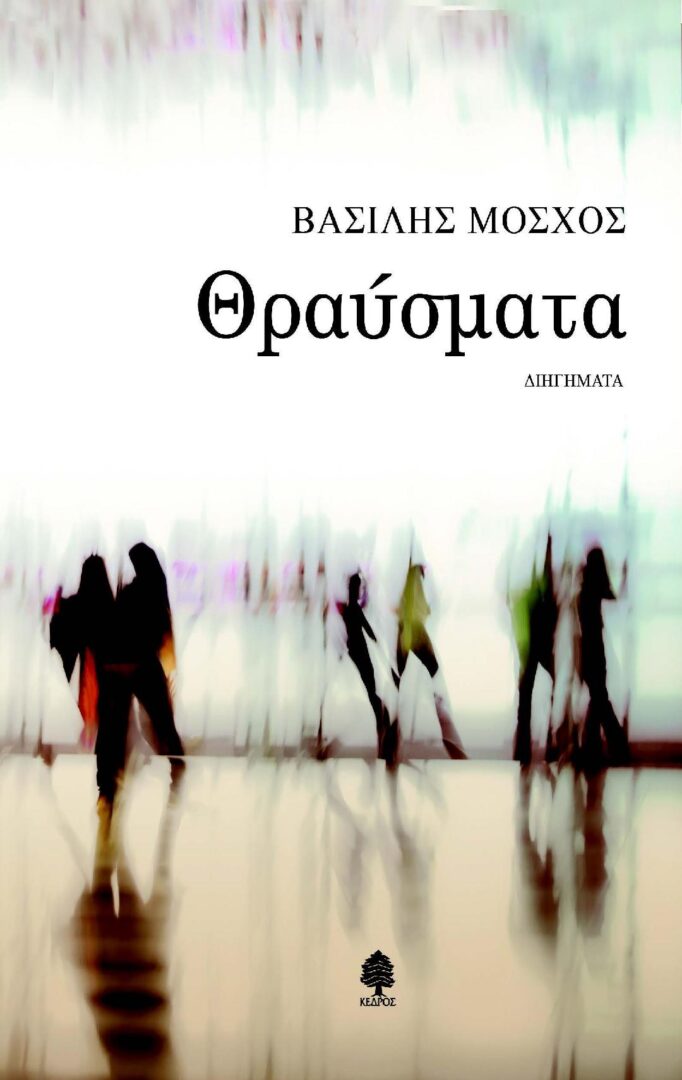

Vassilis Moschos was born in 1987. Ηe is an author and filmmaker based in Thessaloniki. His latest book, a collection of short stories titled Land Rover, got published by Tri.Ena in May 2024. He has also published a poetry collection titled YUNIK (Thraka, 2023) and the short story collection Fragments (Kedros, 2017).

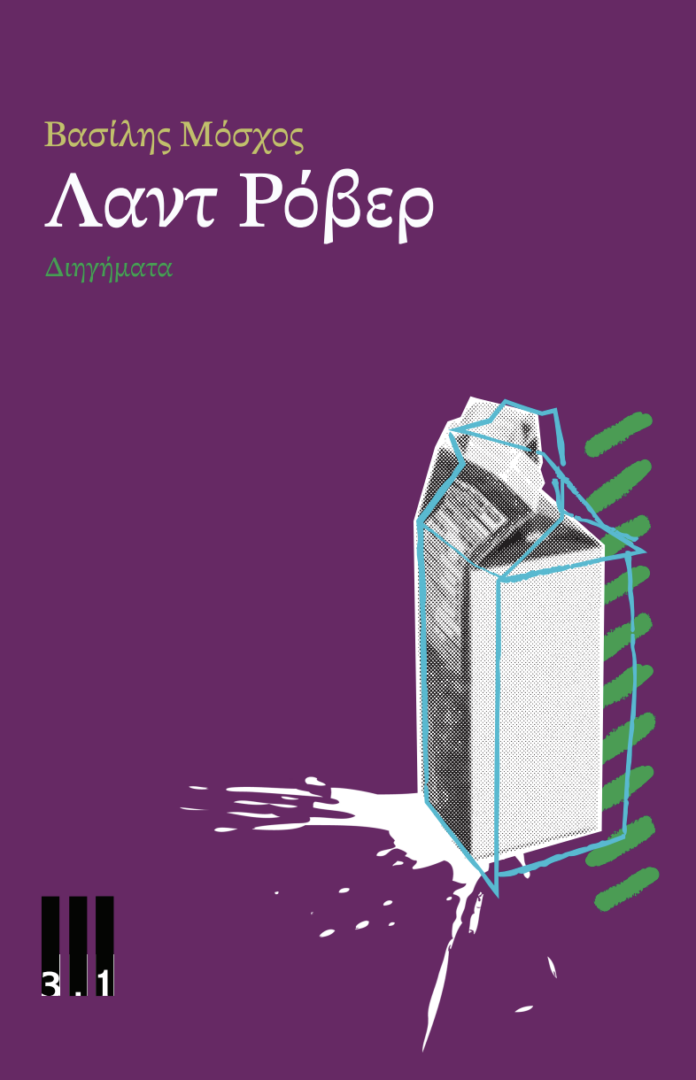

Your latest book Λαντ Ρόβερ [Land Rover] was quite recently published by TRI.ENA (2024). Tell us a few things about the book and the story behind it.

Land Rover is a collection of ten short stories set in the present and the recent past of contemporary Greek society. It is the second book I have written and at the same time the most difficult, both as a creative process and as a publishing attempt, as it took me almost four years to complete it and another five years to find a publishing house for it. I was beginning to despair and come to terms with the fact that the book would never be published, until it found its way into the hands of Kalliopi Pasia at Tri.ena, who showed me unprecedented trust and surrounded the book with unquestioning care.

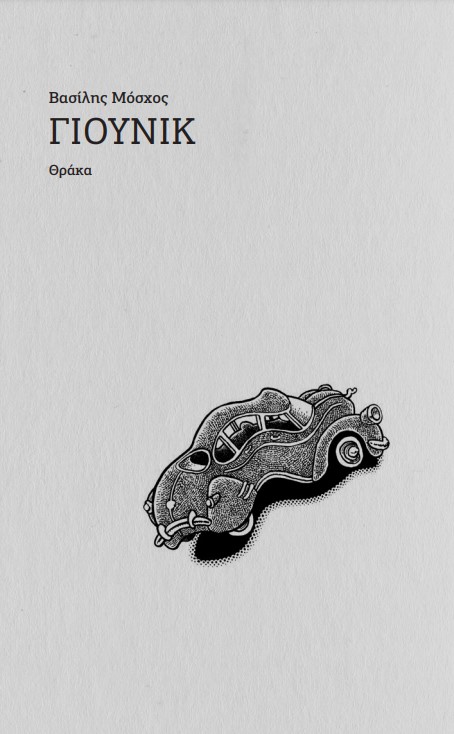

Ιn her review of your poetry collection Γιουνίκ [YUNIK] (Thraca, 2023), Vicky Brousali commented on how your heroes are “people who fight, who resist, even when bridges cannot bear the weight and collapse”, “for all the unprivileged, the defeated”. Where does the personal meet the political and the collective in your poetry?

In every form of art, and therefore in poetry as well, the personal and the collective/political are inextricably intertwined, even if that was not the intention of the artist or even when they explicitly seek their disconnection. We are integral parts of a whole in biological, social, historical etc. terms and this is inevitably reflected in our work. What differentiates each voice from the others is the focus and the extent.

In terms of the characters I write about, they are people I happen to know well. Both my short stories and my poems feature people from my city, people of my generation, people in the neighborhoods where I’ve lived, people I observe and interact with on the street, at work, on the bus, in the bar, at the supermarket. They couldn’t be on the “winning” side of this world even if they wanted to; they don’t have the right to stop fighting even when they want to give up. If this manages to reach readers, I am very happy and pleased with myself.

How does literature converse with the world in inhabits? Could it be used to imagine what could be radically different realities?

Literature is literature and reality is reality. Literature (as well as the cinema, music, painting, the theatre, etc.) is a refuge, a comfort, a consolation, an inspiration, an entertainment, a rest, an uprising, a thrill, everything. We read and write it to give meaning and order to something as messy and incomprehensible as life is by definition. To answer that “why” of our childhood that is doomed to remain unanswered forever.

Reality, on the other hand, is inexorable. For example, not being able to make ends meet while working 8-10-12 hours a day, dreading the possibility of your child getting sick or your account running out of money ten days before your next pay check, not even being able to afford a setback, a mishap; these are all serious things, not a laughing matter. And they shouldn’t be treated lightly by people involved in literature, regardless of their position.

I am really annoyed by the complacency surrounding literature, that people who write supposedly serve something higher, something transcendent, while people who read fetishize the reading experience in terms of the aesthetic and cognitive capital that they ought to accumulate incessantly. And this assumes disproportionate proportions through the internet and social media.

Literature cannot by law transcend life and reality, as long as it emerges from it, and not the other way around.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

The most important one, I suppose. Both organically and as a mode of expression.

I’m particularly concerned that the language of the characters in my writings is real, that it is the language that a person would speak if they were a real person in real life out there, with the particular characteristics and the specific life experiences; that there is truthfulness.

In addition, I am interested as a writer and a poet that the language spoken out there should be found in literature as well, that it should be captured and preserved as such. In recent years, various experts aiming to dictate how we should and should not write literature have awakened from their historical slumber, and they do not hesitate to attack the language spoken in our present era, reviving disputes and passions of the language question that have always been political in nature – neither aesthetic nor grammatical – no matter how hard they try to convince us that the sun rises in the West.

I was born and grew up in the Greek North, where crimes were regularly committed because of the language spoken by the people. It was forbidden to speak the language you spoke from birth, to sing the songs you had already heard from your mother’s womb, Slavic (Macedonian, Pomak), Turkish, the idioms of the Anatolian refugees, Sephardic Hebrew, all these languages and speeches had to be suppressed in the service of a collective fantasy of a single “nation”. These things cannot be easily forgotten even today.

Some years ago, I had to vigorously argue for the preservation of bits of local dialect in the language of some characters in my writing, explaining to the (otherwise impeccable) proofreader that, for example, an elderly couple of refugees from Asia Minor living in Thessaloniki could not speak differently. The answer I received was “you are right Mr Moschos, but our language is not spoken like that, what can we do now”. Well no, no one can convince me that this is not a political stance, or an ideological choice, for that part.

I want to defend the language I speak, and if I can do that through my work I will have something to be proud of in my later years.

Which are the main challenges that young writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do the social media play in the promotion of new literary voices?

The biggest challenge facing younger writers in our country is that they have to finance the publication of their works themselves. The exorbitant sums extortionately demanded by publishing houses to publish works by newcomer writers is an ongoing and unpunished ‘crime’ against our country’s literature, the full effects of which will be seen a few decades from now, though they are already becoming quite evident.

As we speak, we seem to voluntarily cede the art of discourse to a certain portion of the population, with all that this implies for artistic production, but also for criticism and theory, in the long run. And it’s quite disturbing that nobody seems willing to talk about it. Obviously because the majorities are comfortable within this framework.

As for the second part of the question, the power of social media in promoting younger literary voices is clearly overestimated. On the contrary, as the years go by, I have come to realize that the whole attempt to promote oneself through the social media is a big trap.

Unfortunately, it’s no longer enough to simply write a book, regardless of whether it’s good or bad. Writers now have to be at the same times editors of our own work, learn to sell ourselves in marketing terms, learn to sell our work almost in retail, learn to find time and space to acquaint with our peers, and hunt down critics to write for us, to do public relations in this ever-growing parallel network of events/presentations, to make sure that we are always available if we are invited to participate in an event, and of course, until we have another book out in the market, to make sure that we are often published in magazines and newspapers, so that our name stays on the spotlight.

No wonder writing has become the privilege of the few and privileged. And were it not for the sword of Damocles of self-financing, only people who don’t have to work for a living can run their daily lives at such a pace.

For the majority of Greek writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. Would you agree that earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule? Could things be otherwise?

Of course. And as corrupt as the literary and publishing ecosystem is, there is no way things could be otherwise. Personally, I have come to terms with the fact that I will never be able to make a living from writing, let alone succeed in making a comfortable living from it. But I don’t mind. It’s a small price to pay in order to maintain an integrity, at least as I understand it, and a freedom in how I perceive writing, to return to your second question. And creation without freedom cannot exist. At least as far as my writing is concerned.

Unless we are willing to talk about a radical reconstruction of the entire industry, about structural reforms across the entire spectrum of book production and marketing in our country: legislative, labor, insurance, publishing, financial, business, political, etc. But does the book world in Greece really want such sweeping changes? I would certainly hope, but I don’t think so.

*Ιnterview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE