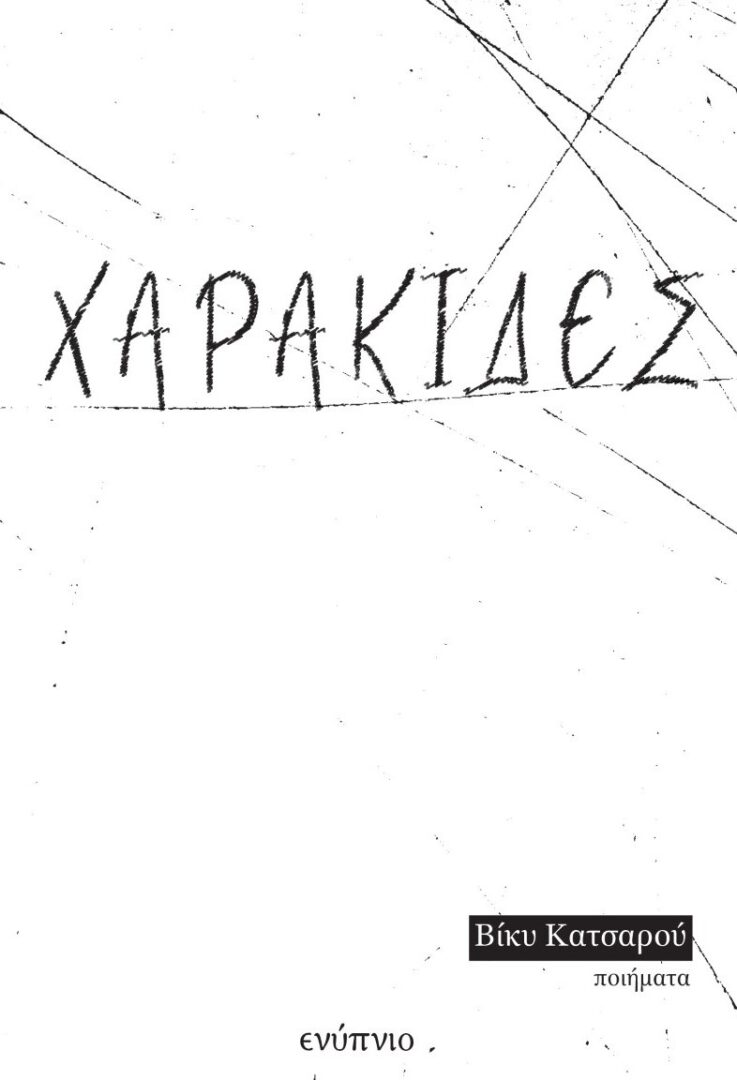

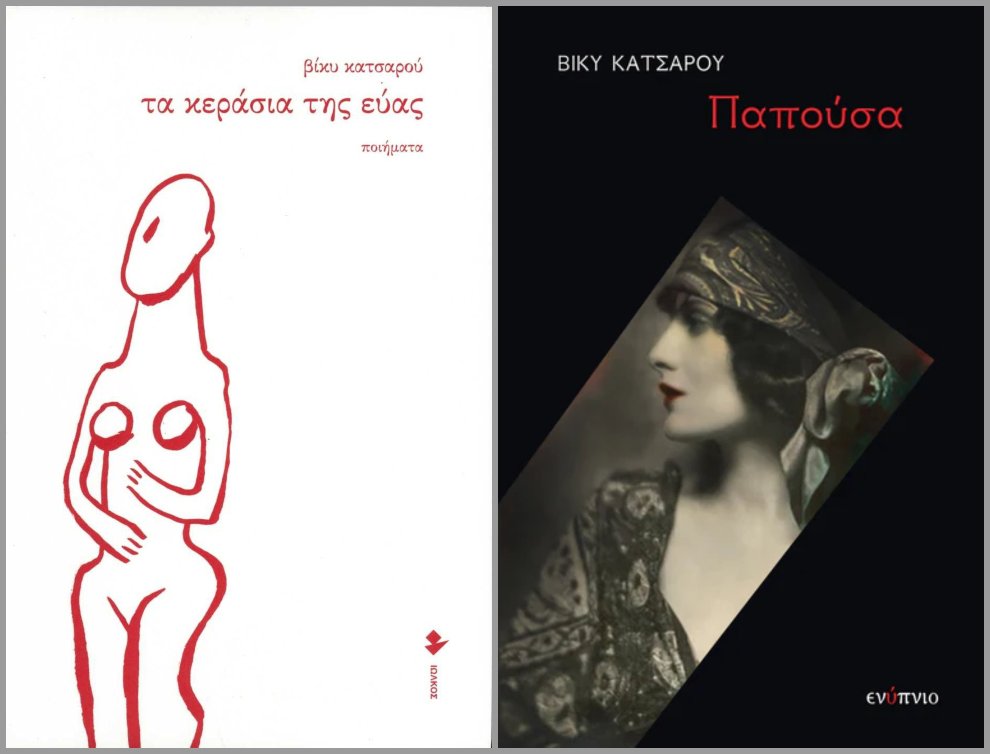

Viki Katsarou was born in 1987 and lives in Athens. She is a graduate of the Department of Classics of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. She has done post-graduate studies in Greek Language and Literature, in Theater Studies and in the 8th Workshop of Publishing Editors of MIET. She has been working as a translator and editor for several years. She is the editor of The Ascent, the unknown until recently novel of Nikos Kazantzakis as well as of all of his new editions by Dioptra Publishing. She has written two poetry collections, Τα Κεράσια της Εύας [Eve’s Cherries] (Iolkos, 2018) and Παπούσα [Papusza] (Enypnio, 2021). Χαρακίδες [Scarred Women] is her third poetry book.

© Dimitris Kavouras

Your latest writing venture Scarred Women was recently published by Enypnio. Tell us a few things about the book. What about the title?

The title was inspired by a story I read about women in Lefkada during the Venetian rule in the Ionian Islands. It is said that they marked them on the face so that the Franks would not kidnap them. Thus, this myth inspired a collection of 44 poems dealing with the trauma of women. Obviously, the woman in love comes forth sometimes as a goddess, sometimes as an anonymous poetess and sometimes as a maenad; the woman who is constantly consumed by society, the woman who is in a constant internal dialogue about issues like motherhood, existence, value of life, loss, death, politics.

You dedicate the book to the women of your generation, those who died prematurely, were abused, excluded or differed from social norms. Ηοw is gender approached in your poetry? Would you say that there is an increasing focus on gender on contemporary poetic production?

My poetry has always been gendered, since my first book. However, in the last three years I have seen a sharp increase in young poets turning to gender issues, and I can only find this hopeful. Also, yes, I dedicate my book to women who have died prematurely or violently, but also to the women of my generation by including the matrilineal continuity of each of us. Every woman is the sum of the women who came before her, every woman is the sum of her traumas, every woman is the sum of all the women who were oppressed, whether or not they fought against patriarchy. I myself feel that I am standing here today because some other women succeeded and survived before me.

All your three poetry collections seem to draw inspiration from collective myths. How does reality interweave with mythological and historical elements in your books in your poems? Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

I draw from collective myth, which is intertwined with personal experience. When I sit down to write I am ready to do so. I will have already read enough, make drafts, I will have collected experiences. I like impersonating women and changing their history. I also find it a form of justice. They live through me and I live through them. I am always interested in the woman, the trapped woman, the enslaved, the caged woman, who ends up a rebel woman, a resurrected woman. In my first book the protagonist was Eva, who was not exiled, but left voluntarily because she refused to submit to an imposed love that was only demanding. Thus, she overturned the balance with the God-Man and wanted to re-establish a new form of relationship between them. My second book is more socially concerned apart from feminist. The same woman is incarnated again and again as a witch, who is constantly burned at the stake because she is disobedient to the rules of her time, and finally she chooses her last incarnation, that of the poetess, Papusza. A poetess cursed and exiled because she writes poems when she is not allowed to because she is a woman, but who in the end will gain not only full acceptance but also the leadership of her tribe.

Υοu are the editor of The Ascent by Nikos Kazantzakis, which was recently published by Dioptra. Tell us a few things about the historical background as well as the plot of the book.

In the mid ‘40s, after Zorba the Greek, Kazantzakis wrote The Ascent, an esoteric text, characterized by deep and liberating melancholy. His action takes place immediately after the war, in Crete and England. Kosmas, after an absence of twenty years and his major offer to the war, returns to his hometown, Megalo Kastro, together with his Jewish wife, Noemi, who carries the universal memory of the Holocaust, a woman who questions the value of life. Only a few days have passed since his father’s death and Crete is counting its wounds recalling personal stories of courage and pain. The man who comes out of World War II is a man who cannot think, a man who has not been saved, who is in danger, and Kosmas goes to post-war England to save this man. The personal cost of his choice is enormous. But this is the debt, this is the burden we all have to live with.

In this work, a number of autobiographical elements and real incidents of the Cretan writer’s life are brought to light that are part of the unpublished novel. Typical examples are (a) his BBC radio talk about Bernard Shaw, (b) his appeal to the intellectuals of the world for the establishment of an “International of the Spirit” and (c) his experience of recording the German cruelty. It is therefore a hybrid prose, between myth and history, which on the one hand assimilates real events, and on the other transforms different types of literary writing, revealing them masterfully in the author’s workshop, which in this case is the exuberant mind of Nikos Kazantzakis, who through his travels gathers images and experiences, and transforms them into art and letters.

Today, the necessity of the publication of The Ascent is especially proven, as it is a socio-political reflection of the post-war era of both Greece and Europe – and especially the English territory – through literature. Thus, a work with a clear anti-war character and a strong political message can consciously awaken its readers. The purpose of the book is to express its concerns both for the Greek and for the global political and social reality.

What is that makes the work of Kazantzakis both timely and timeless?

For Kazantzakis, beyond a formidable narrative ability, this element is the core of his speech. A deeply existential discourse, which confronts the great questions of man: life, death, God, man, freedom as a constant struggle, the ascent towards a life with value. No era can disregard these concerns, no screen can bypass them.

Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published? What role do social media play in the way people read and write? How is language affected in this respect?

One difficulty is that there are huge numbers of books being published that you can’t keep track of. Also, another difficulty focused on poetry is the small number of readers. An additional difficulty is being an unintegrated and lonely person, who does not easily join circles. I am not against social media. I at least know how poets of my generation use them: as emotional outbursts against injustice, existential crisis, social commentary, political positioning, as a means of making my struggle heard. But, on the other hand, I recognize that all this distraction they have brought has a negative effect on writing and reading by impoverishing the language.

How do young writers relate to world literature? Where does the local and the national meet the global and the universal?

We read translated literature enough, while access to translated literature is now easier than ever and it is up to us to indulge in this osmosis. In addition to this, I think that crucial steps have been taken in this direction in recent years on the part of many publishing houses.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE