Yiannis Antiochou, poet and translator, was born in Athens in 1969. He grew up and lives in Piraeus. Antiochou holds an MBA and Master degree from the Medical School of Athens, specializing in ICUs and ISO standards. He has published seven books of poetry and translated poetry of T.S. Eliot, Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Hart Crane, Anna Akhmatova, etc. His latest book is published by Ikaros editions. He has collaborated with various literary magazines publishing poems, essays and translations. His poems have been translated in English, French and Spanish.

Yiannis Antiochou spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest poetry collection Αυτός, ο κάτω ουρανός [Τhis, down under empyrean], noting that the book “looks like the imitation of a tumor cell that begins to multiply and becomes a neoplasm in God’s woven”, “a revolution with the goal of conquering the sacred resonance – God himself that would be dying folded in cosmic night”. He explains that up to this day his “main theme is the body’s sorrow”, while a key person in all his books is “Immortality”, which even though in his latest poems has become “a sound, a sound parasite, she still exists”. He comments that for him “poetry evolves formally through new language appointmens”, and concludes that although “verbal, syntactic and formal experimentation is of great interest”, he doesn’t consider poetry “the theatricalisation of cliché”.

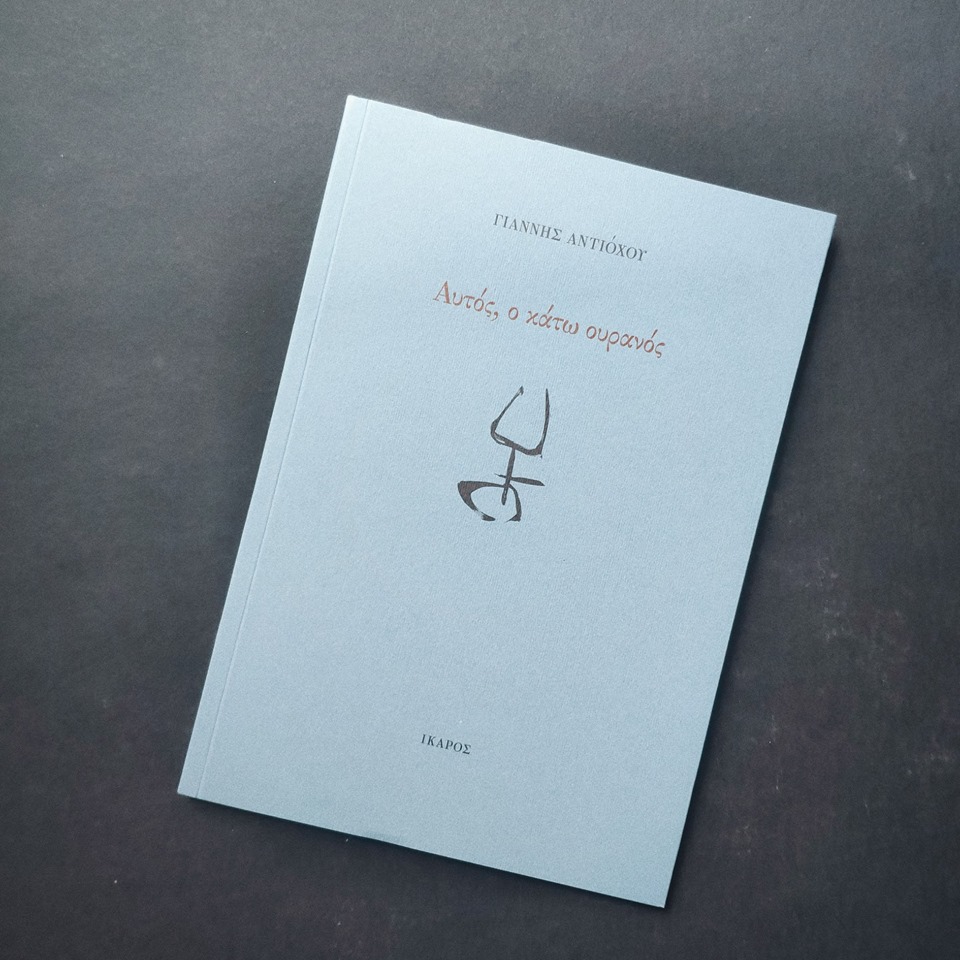

Your seventh poetry collection Aυτός, ο κάτω ουρανός (This, down under empyrean) was just published by Ikaros Publishing. Tell us a few things about your latest writing venture.

I do not know, frankly I never knew how to speak briefly about a book of mine; even now that I am inside its shell. This, down under empyrean is a poetic synthesis whose starting point reminds me quite a lot of my poetic collection, Εισπνοές [Breaths] (2009) by Ikaros editions; a poetic synthesis with constant reflection on a poetic subject. In this book, I have successfully managed to abolish the heterogeneity —of “self” and “the other” —, to set a foot on the crack I have created. This book looks like the imitation of a tumor cell that begins to multiply and becomes a neoplasm in God’s woven. A revolution with the goal of conquering the sacred resonance —God himself that would be dying folded in cosmic night. But this God, believed both by the poet and his poetic subject, has already died in Nietzsche’s “Also sprach Zarathustra”. “Gott ist tot” and the poet devours his very own existence. What a pain! It’s a deeply physical book with an immense difference: language is the body.

Moreover, this book is the migration sequence of timelessness identity, the existence of an individual on behalf of whom I submitted my poetry; a life in a gravestone, hatred of freedom against every conscious view of every known world; my withdrawal, the swan song of a body, for all that while we do not see, we detain their rhythm. In This, down under empyrean the poet is its crack. The light emitted assures me that everything is moving within an extensive stasis. The greatest constant of all is time —this shatter. This book is the scream Irini Papakyriakou let out when playing on a theater stage in Paris: Tu es à moi. Tu es moi. Tues moi.

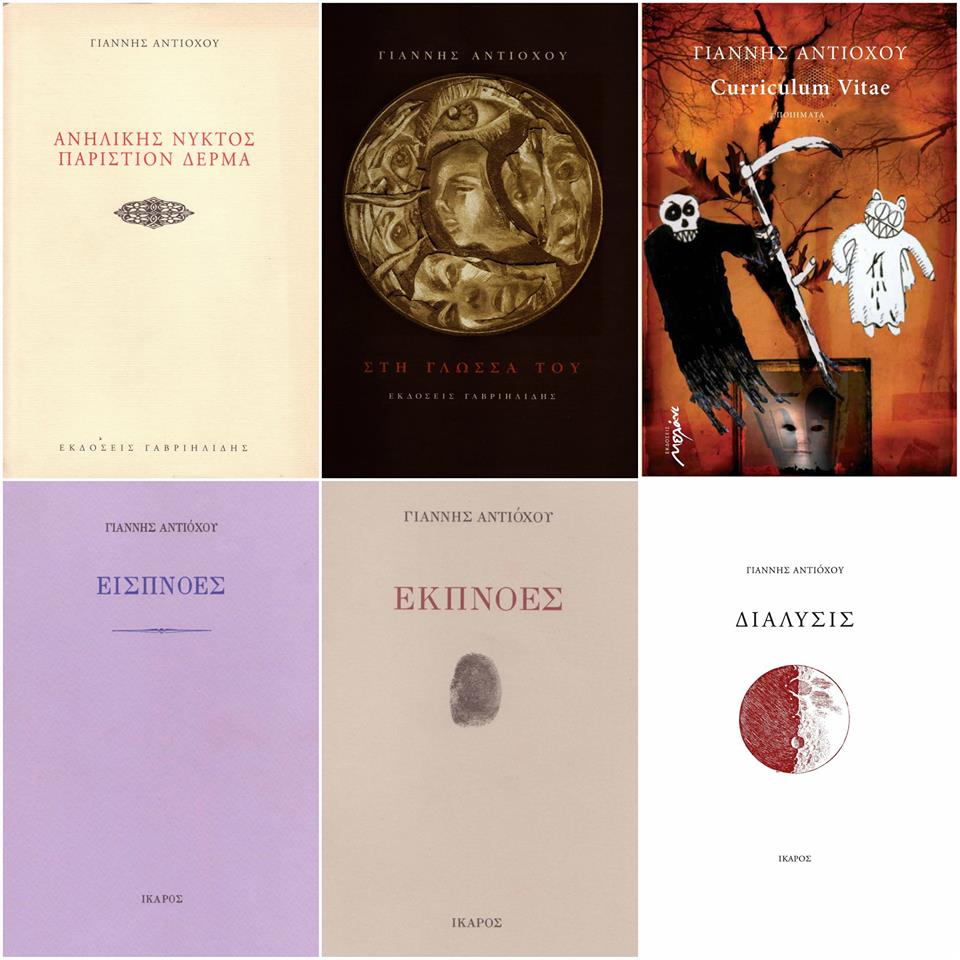

From Ανήλικης νυκτός παρίστιον δέρμα [Minor night’s drogue sail] in 2003 to This, down under empyrean in 2019, what has changed and what has remained the same in your poetry? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

My answer will be a cliché. In fact, up to this day my main theme is the body’s sorrow. What has changed may be formally understood somehow within my poetic form and structure. If I am alive until 2023, I am thinking of gathering my books in a concise edition, presenting my poetry with the coherence that I now see in it. Few poems will be rescued from the first collections, and from 2009 onwards, any books that have been published by Ikaros editions may be incorporated. Then, I will be satisfied as a poet. If some poems could sustain after my death, let the ones I have chosen be sustained. Anyone who perceives my last book This, down under empyrean, will notice that there are specific repetitive signs, verses from previous poetry collections, which was also the case in the book Διάλυσις [Disintegration] (2017). Readers could recognise a key person in all my books, Immortality (Athanassia) —even though in my latest poems Immortality (Athanassia) has already become a sound, a sound parasite, she still exists.

What about language? What purpose does language serve in your poetry?

Language is a body, but I feel somehow that it is getting exhausted. In recent years, I may have been very productive and now it’s the right time to keep up silence. Maybe I am getting older. However, I suffer secretly! My language is running out. An invasive process. I am adopting German phrases trapping a new syntactic agony. I have no answers for you anymore.

To use Thomas Ioannou’s words, “writing requires a stable and robust hand. You need to keep your distance so as to see the big picture, managing to even perceive yourself as a third”. Are there parallels to be drawn between poetry and medicine?

I do not think that Thomas Ioannou’s words are effective for all the poets. Maybe I understand the adjective “robust” but I feel the need to keep dreaming on. My motto is: “carpe diem, carpe noctem, carpe vitam”, so I have faith in the moment. My point of view is that a single moment can create poetry. Extensive workout is needed only to conquer your very own language and I think that I have succeeded to conquer it. You should know that I dream poems, and what happens in my dream world is impressive. A sequence of streets, places, houses and landscapes – patterns of my dream world. I do not know how many people are dreaming the same way. How many follow the very same dream after months? An attempt to conquer the map of my unconscious. I hear and observe everything as in normal life. Perhaps this is my ability to reconstitute 90% of a dream.

There are times when dreamlike patterns make me conscious in my sleep. I am the master of my dreams, but unfortunately, I cannot always change the situations. These dreams I learned to make them poems like: “Moon enters all windows” or “Sentir le fauve” from my last poetry —and how many more; I cannot separate if it was a dream or reality. All my life is somehow a knit with the invisible thread of another world. There are so many things I learned from the dreams that I might want to record as calendar records before my life is over. I already feel more tranquil. It seems like I confess my peculiar truth. No one will confirm it, but that’s not my purpose. My friends will conjure up an aesthetic deviation. My purpose is to unlock the doors that are still locked without the Gatekeeper seeing me. I have a common place with Him —a wide deep darkness. Then, I use both the blade and the catgut suture.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

I am already 49 years old, kinda classy and conservative, so I confess that I write and support this attitude with my poetry. I find weak the poems that somebody – in order to make the reader perceive them – should make performances about or build up impressions reciting them, breaking word for word. Let others do this. There are of course some poets, who do it very well, but this is another assignment. It is also very difficult to distinguish good poetry within social networks, since usually it is good even though it is exhausted in the few characters that promotion allows. I have almost stopped attending presentations where poetry is portrayed with cheap materials —Arte Povera is something different. There is a main axiom in art: you should respect the audience. I do not care about all this, nor do they bother me. You know the picture swallows us. I attempt my own images not to overlap reality. For me, poetry evolves formally through new language appointments. In fact, verbal, syntactic and formal experimentation is of great interest, but I do not consider poetry the theatricalisation of cliché.

“Translation is not a mere transfer of a given ‘original’ from one language into another, but a process by which an original is, in a sense, ‘fixed’ or created, as translators often have to adjudicate between multiple editions or versions of a text”. In this context, where does the role and responsibility of a translator lie?

I am not a professional translator and, therefore, I have the choice to translate poets that for me is another self. Translation is just as hard as poetry. I, personally, see it as a transfer to my very own language. So, I am trying hard to live within the poet’s body. What Karen Emmerich says, I think it is the core of translation. I’m translating between writing my books, it’s a way to pause my “mannerism”.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE