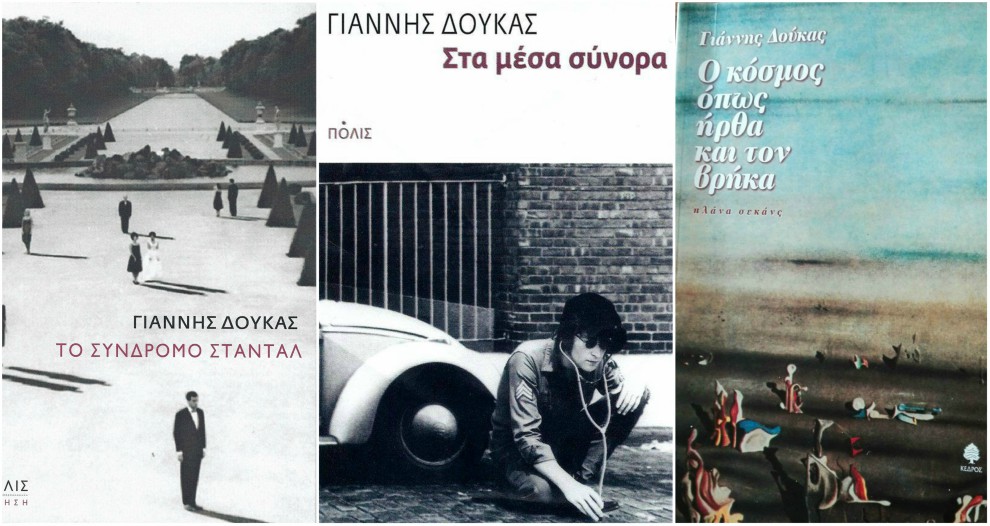

Yiannis Doukas was born in Athens (1981). He studied Greek Philology and Classics at the University of Athens and Digital Humanities at King’s College London. He has lived in Ireland, where he worked towards a PhD at NUI Galway. His books so far: The World as I Came and Found it (Kedros, 2001), Inner Borders, (Polis, 2011, Diavazo journal Debut Poetry Collection Award) and The Stendhal Syndrome, (Polis, 2013, G. Athanas Award of the Academy of Athens).

He translates from English. He worked, along with Haris Vlavianos, on the erotic poems by e. e. cummings (Patakis, 2014).He has published book reviews in Greek newspapers and literary magazines. Some of his poems have been translated into English, French, German, Serbian, Dutch and Polish.Two poems from the Inner Borders have been set to music by Nikos Platyrachos (Ta Astega, 2015). He has written the lyrics for two songs by Thanos Mikroutsikos, included in the album Stin Omihli ton Kairon (2017).

Yiannis Doukas spoke to Reading Greece* about the main themes his poetry touches upon, noting that “I write about the things I notice, how I distil them, I write about the past, the many ways it survives under and around us, I write about people long gone, as I mirror my existence in theirs, I write about humanity and how it is tested against our times”. He comments on the conversation of poetry with tradition and established norms, “a conjunction of irony an nostalgia”, as well as on the way technology is combined with poetry, explaining that “the composite sequence of techne and logos, whatever the order, can be understood as a unified system: this is just us and what we are creating”.

As for the extraordinary burgeoning of poetry that has been noticed in recent years, he notes that “we do witness a re-invention of the genre at least in terms of its extraversion”, wondering however whether “we actually seek contact, or feign it, when all we need is narcissistic confirmation”. He concludes that “recent efforts, such as the ones by Karen Van Dyck (Austerity Measures) and Theodoros Chiotis (Futures), have definitely raised the visibility of Greek poetry particularly in the English-speaking world”, yet what he hopes is that “in the long run we will manage to avoid the folklore of glorified misery and squalor”.

What drove you to poetry and what is your driving force? Which are the main themes your poetry touches upon?

In my own private tropical forest of shelves, what must have driven me to poetry were the thin wrinkled spines of the books, their titles, obscure, and then, when opening the cover as a gate, the release to metaphor, beyond the well-worn language of the everyday. The unsuspected exposition to poetry’s epigrammatic immediacy, its puzzling allure, its challenge, its ability, as T.S. Eliot would have it, “to communicate before it is understood”. With the luxury of a home-bound treasure hunting and the access to a breathing mythology, I was able to dare my first teenage attempts, however naïve and childish, enchanted by the “bright sequence of the sparks” or resisting it.

Since then, I’m writing in order to find my “most individual parts”, often far away from me, understanding poetry as a means to realise, accept and reconcile my own temperament, console and be consoled, tame the chaotic fluidity experienced both within and around me, shape my feelings and thoughts, play with form and explore language, read myself as other, step outside and connect myself to the world.

I draw on everything that is part of my life and from wherever I fix my gaze: sometimes it is politics and current events, in the way they affect me, sometimes the places I live in and what populates them; also, what I read and where I browse, as I visit the digital cabinet of curiosities, as I co-produce the ever-changing giant mosaic of the global electronic text. I write about the things I notice, how I distil them, I write about the past, the many ways it survives under and around us, I write about people long gone, as I mirror my existence in theirs, I write about humanity and how it is tested against our times.

In a post-modern world, how does poetry converse with tradition, history and established norms?

With a conjunction of irony and nostalgia: we torment ourselves with self-awareness, we renegotiate our identity (or, rather, multiple co-existing contradictory identities), we start, after all, from a redefinition of what tradition, history and established norms are. Doesn’t it go without saying that history invites personal, emotional readings and that tradition, in its invention, might be constructed as a patchwork of separate, definitely transnational, elements?

As far as I’m concerned, sometimes I feel as if I’m building “a moment’s monument” or rather drawing a portrait from memory: but what do I look for in the past that is not already within me?

“Given that the stimulus that triggers poetic creation can be found anywhere, I see nothing competitive or incompatible between poetry and technology”. How is poetry combined with technology in your work?

If we dare go past a phobic neo-luddite understanding of technology as an enslaving convenience, we’ll remind ourselves that it actually consists of an all-encompassing array of methods and techniques, the sum of human craft which forms and builds our everyday life. The composite sequence of techne and logos, whatever the order, can be understood as a unified system: this is just us and what we are creating.

Therefore, technology might be combined with anyone’s poetry (and mine) in a variety of ways: even if I opt to narrow it down to the personal computer, its function as a typewriter, a library and a telecommunications device converts it into a field where the whole poetic process, from observation and early conception to writing and dissemination, takes place. Technology also alters the parameters and settings of our own behaviour (but not its essence). How do we remember now? Don’t we use the written word much more? Isn’t it, though, gradually transformed?

Would you agree with those who support that the field of Digital Humanities doesn’t just change the framework of research but may lead to the development of a new paradigm?

The Digital Humanities, we could argue, are just the same old Humanities, at a time where the digital medium coexists with print or even takes primacy over it in the process of knowledge production and transmission.

Not only this, though – the abundance of available sources and the new possibilities for collaboration, beyond the boundaries of traditional academic disciplines, alter not only our methodologies and potential conclusions, but also our very understanding of what we are studying: its nature, content and significance.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How is this trend to be explained?

We do witness a re-invention of the genre at least in terms of its extraversion: a rise in publications, the use of digital outlets, including social media, which allow for instant sharing and wider distribution, and a claim for the public space and discourse, especially within the recent political context – even the nature of the poem itself, short as it is in size, with the potential to convey messages in an immediate manner. It is far easier now to put ourselves in context, both locally and internationally, to network with each other, to communicate and co-ordinate.

Let us not forget, however, that poetry is still addressed to an extremely small audience; its writing does not breed equal amounts of readership. Do we ever really go outside the bubble? Not to mention that a large percentage of the poetry written today is preoccupied anyway with the self and one’s own reflections in the mirror: do we actually seek contact, or do we feign it, when all we need is narcissistic confirmation?

It has been argued that the crisis has rekindled the interest of foreign readers in Greek poetry, with an increasing number of Greek anthologies being translated in English. What is it that makes a national poetry appealing to a foreign audience? And, in turn, to what extent do Greek poets incorporate foreign influences in their work?

Recent efforts, such as the ones by Karen Van Dyck (Austerity Measures) and Theodoros Chiotis (Futures), have definitely raised the visibility of Greek poetry particularly in the English-speaking world.

Of course, this kind of publicity cannot be understood outside the context of our recent and current political and financial affairs – I guess we became relevant as early witnesses and test-cases in economic hardship, the rise of the extreme right, the refugee crisis and so on. When –if ever– the aftertaste of all this wears off, we will be able to sit back and evaluate its actual range. I do hope that in the long run we will manage to avoid the folklore of glorified misery and squalor.

As for foreign influences, they have always been a quintessential part of writing in its evolution – much more so now, within the globalised continuum, where contemporary developments can be easily followed, and most of us have lived abroad, even for a little while. But long before that, any poet (writer or artist) had to look beyond the borders and limits of one’s own language and homeland: there’s no such thing as a solely national history of culture.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE