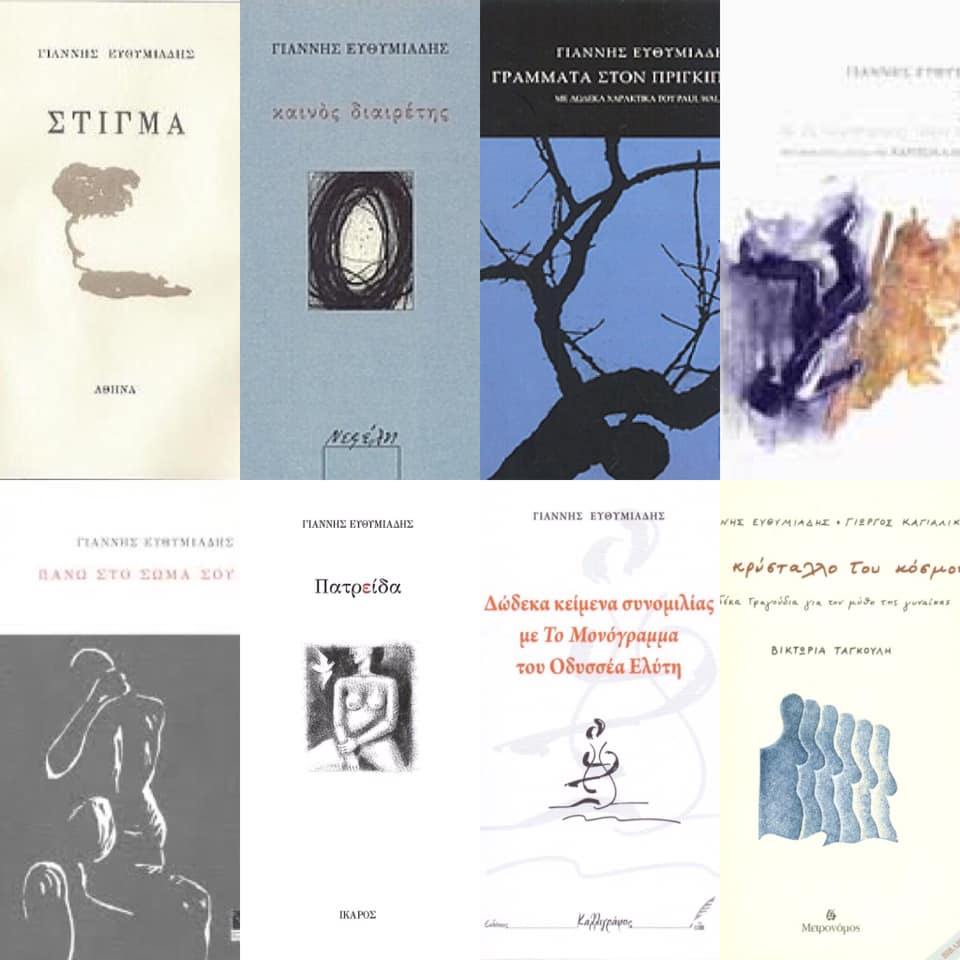

Yiannis Efthymiadis was born in Piraeus, Greece in 1969. He studied classical philology (National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, 1991) and undertook postgraduate studies in ancient Greek drama. He has published seven books of poetry: Στίγμα (Stigma), privately published 2004, Καινός διαιρέτης (New Divisor), Nefeli 2007, Γράμματα στον Πρίγκιπα (Letters to the Prince), Mikrι Arκtos 2010, 27 ή ο άνθρωπος που πέφτει (27 or the Falling Man), Mikri Arktos 2012, Πάνω στο σώμα σου (On your Body), Mikri Arktos 2014, Πατρείδα (Motherland), Ikaros 2018, Αλκίνοος (Alkinoos), Nefeli 2021 and the literary essay 12 κείμενα συνομιλίας με Το Μονόγραμμα του Οδυσσέα Ελύτη (12 texts of conversation with The Monogram of Odysseus Elytis), Kalligrafos 2014.

He has also translated British and American poets, while his poems have been included in Greek and foreign anthologies and translated into English, French and German. The poetry collection Το κρύσταλλο του κόσμου (The Crystal of the World) was set to music and recorded by Metronomos (2006). Yiannis Efthymiadis is also a teacher, he has published philology books for the secondary education while he also collaborates with literature magazines, printed and digital. Between 2015 and 2020, he attended the Athens School of Fine Arts. He has participated in three solo exhibitions and nine collective ones. As a visual artist, lithography and watercolor painting are his main interests.

Yiannis Eftymiadis spoke to Reading Greece* about his latest writing venture Alkinoos, a poetic monologue which “touches the notion of love both in its physical and metaphysical dimension, outside time, beyond gender, where the being meets the non-being”. He commented that what remained the same in his poetry throughout the years is “the persistent, almost obsessive intention to experiment, to move to uncharted poetic waters”, and at the same time his conscious decision for his language “to become all the more simple, [his] expression more frugal”. He also characterized art as “a battlefield in which we are confronted with beauty and truth”, where “the poet, the artist, is doomed to be crushed under the supreme majesty of beauty, of the unspeakable, of the not yet formed”, and concluded that although “art has never changed the world”, it took it “to greater emotional depths, so that it faced the challenge of its own existence”.

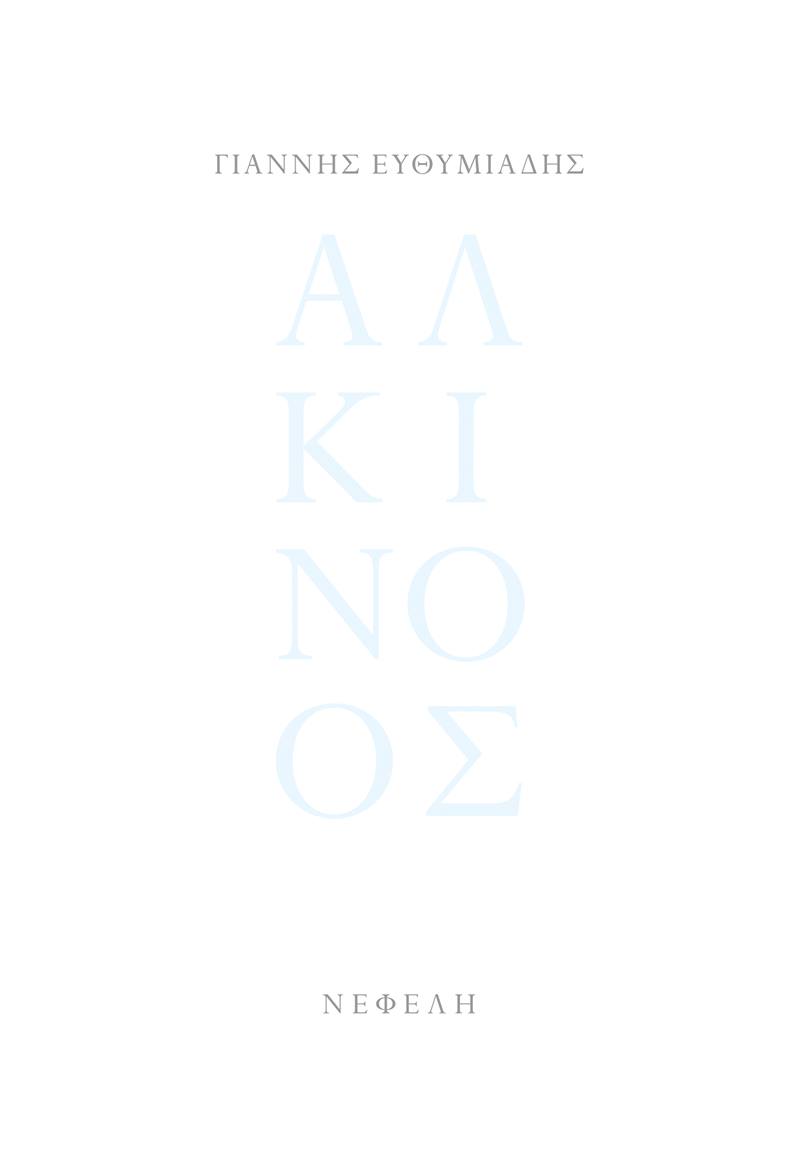

Your latest writing venture titled Alkinoos is soon to be published by Nefeli. Tell us a few things about the book.

Alkinoos is a poetic monologue written during the last seven years. In fact, it is a long love poem. It touches the notion of love both in its physical and metaphysical dimension, outside time, beyond gender, where the being meets the non-being. And it is at that point that indelible and invincible love sparkles. It is there, on the border between life and death, that each one of us takes off any pretense or better yet, puts on his true essence. And that’s where love becomes the supreme power that leads to our self-consciousness. It begins as a carnal experience, becomes a spiritual methexis and ends as a metaphysical release.

In this poetic work, I tried to stick to the boundary between the traditional meter and the modern free verse and was led, almost effortlessly, to a free verse poem, capable of expressing the pulsating erotic madness.

It is due to the “musicality” of the work that some excerpts have already been set to music by my now dear friend and sensuous composer Yiorgos Kagialikos and will soon be released in the form of a cycle of songs masterfully performed by Vassilis Gisdakis.

Alkinoos marks my return to NEFELI, the publishing house from which I started. I am very happy that my poetic vision converges with the publishing vision of Periklis Douvitsas.

From your first poetry collection in 2004 to Motherland almost fifteen years later, what has changed and what has remained the same in your writings? Are there recurrent points of reference in your books?

Poetry is, in its essence, an endless quest. The poet should chart his poetic path being fully open to all possibilities, to any poetic surprise, to the overthrow. Only in this way can his poetic work proceed and with it poetry itself. If we consider the fact that poems, for centuries, have been telling again and again the same things, dealing with the same issues, expressing the same or similar needs, then what every poet should aim at is to tell these same things in a different way; in the way that his personal sensitivity as well as the thought and language of his era dictate.

Thus, also in my case, throughout these eighteen years that I write and publish poetry, I could say that I am the same but also always different. If I had to focus on one or two recurrent points, I would say that what remains the same is the persistent, almost obsessive intention to experiment, to move to uncharted poetic waters, with my love for language and humans as my only compass. As for what changed over all those years, I would say that it was a conscious decision on my part for my language to become all the more simple, my expression more frugal, my thought fighting to reach the essence of our existence.

There were times when my poems were more internal and confessional, while there were others that they became more extroverted and screaming; yet I have always been interested in my gaze on human beings becoming more and more penetrating and on my language becoming more and more terse.

Ιn Motherland you seem to converse with our poetic tradition. How do you grapple with the burden of history and with the ‘giants’ of both ancient and modern Greek poetry?

Every poet, every artist in general, is taught his art by his ancestors. He bends over their work with love and dedication, trying to decode it, first to imitate and later to creatively reconstruct the material he received. Because the history of art, of poetry, is nothing but a chain in which every link, no matter how small or large, strong or weaker, is equally important for it proceed smoothly through time.

Just as an apprentice who learns close to a worthy craftsman, a very capable craftsman in this respect, as soon as he understands the secrets of his art, spreads his wings free to begin his autonomous course, so the poet studies his predecessors, and keeping the tools and means that satisfy him and help him realize his vision, walks his own poetic path.

Yet, it’s quite often the case that the apprentice and the poet remember their teachers, either secretly smiling that they have managed to overcome them or by secretly smiling because they still admit their value and continue to repeat them.

In Motherland I experimented with various traditional poetic forms exactly because the work refers to a country I am familiar with, in which we all live in, witnessing it gradually losing its traits. I don’t necessarily mean that it heads towards something worse, but definitely towards something different. And in this relay race, the materials of the past are necessary at times to function as a support for the new construction and at others to act as a resounding counterpoint to the new.

What about language? What role does it play in your writings?

Language is a tightrope on which the poet, like an acrobat, tries to test the endurance of poetry, but first and foremost his own endurance. It’s the breath of the poetic speech. The pulse that bleeds it. It’s the weapon used either for attach or for defense. It’s an operating base and a shelter. The language is carved on the materials of poets and their poems. Sometimes on a rough surface, it takes shape and form; at others on a smooth surface, it gets an exquisite finish. This is how, as far as I am concerned, our language, the language of every people, moves forward by every confrontation of poets with language.

Language in my poems, without characterizing them as language-centric, plays such a pivotal role that it often determines the course, the fate, as I often think, of the poem. It is a word, a sound, a rhyme that often unfold and reveal before your eyes whole poetic universes, unexplored places, oceans inviting you to enter and explore. And language is a relentless judge of both beauty and truth.

“The confrontation with poetic speech, with art in general, is a battle lost before it is even started”. Tell us more.

Art is a battlefield in which we are confronted with beauty and truth. The poet embarks on the struggle to confront those who preceded him, his contemporaries as well as those who will follow. With the older ones to interpret and move them forward, with his contemporaries to emulate them, with those who will follow to define, in their absence, their own struggle before they are even born. He is also confronted with the poetic phenomenon itself, which moves beyond eras and humans. The poet, the artist, is doomed to be crushed under the supreme majesty of beauty, of the unspeakable, of the not yet formed. And he truly serves this idea, he is submitted to the service of art. It’s only in this way that he can make great art (and by great I mean the one that can entice others to beauty and truth), when he forgets his own existence and instead becomes the spearhead, the tip of the pen, to rewrite the same ever human history. And contradictory though it may seem, it is nonetheless necessary to enter this struggle with an equal amount of vanity and humility.

How does poetry relate to the world it inhabits? What role is poetry called to play especially in times of crisis?

Art has never changed the world. It has only made the world reflect upon its existence. It took the world to greater emotional depths, so that it faced the challenge of its own existence. Beauty has always been discarded from its era. The same goes nowadays. Poets have always been fighting on the sidelines to express these things. And maybe this is exactly what saves them, what saves poetry itself. Being on the margin, it can maintain its autonomy, comprehensibly observing while also keeping the necessary distance, not succumbing to any temptation, to any commitment. And there, at the very edge of things, it strives to become the rule almost invisibly.

You have characterized postmodernity in poetry as an extreme liberation, a full exoneration. Could you elaborate on that?

For me, postmondernism as a concept refers to the overthrow of any framework, even if it concerns the movement itself. In fact, in the vast world we live in, we have come to realize that it is impossible to distinguish between the one and the other. The same way as every human being has its own inalienable value, every way of approaching art has an underlying reason and a concrete role. Nowadays the artist doesn’t belong to any movements or groups, or even friendly gatherings. And as frustrating as this may seem to our collective consciousness, our shared companion life, it is nevertheless utterly liberating for the artist who, by definition, claims his absolute freedom as a precondition of his identity. Because in case we gained access to the inner world of the artist, we would see him stand up and fight first and foremost against himself, then his peers and then all the other people. It’s the only way for the new to rise; the one that will bear on its back the world that is emerging.

“Art is the most well-hidden secret and in this sense anyone who finds ways to decode it becomes partly co-creator and co-owner”. Where does the poet meet the visual artist in your work?

The poetic conception of the world is one and the same. And this is true not just for the artist-creator but also for every person who captures the world poetically, that is, freely and creatively. And just as the reader becomes the poet’s accomplice in decoding the message, so the recipient of any art at times contributes to influencing, at others to interpreting or even to judging or reconstructing the messaged it unleashes.

Even within the artist himself, the creator and the recipient co-exist, given that the artist should be both the most ardent supporter and the strictest judge of his work.

And if he happens to be involved in more than one art, then he is in a peculiar and at the same time magical position not to be divided between them but rather for the one to complement the other. In my case I find the “poet” as a creator who expresses himself sometimes in words and at others through images depending on the message to be conveyed. After all, for centuries now poetry has been characterized as talking painting and painting as silent poetry.

This is how I understand the relationship among the different expression of the same or often similar stimuli. And if the branches of my art ever take different directions, the roots remain the same.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE