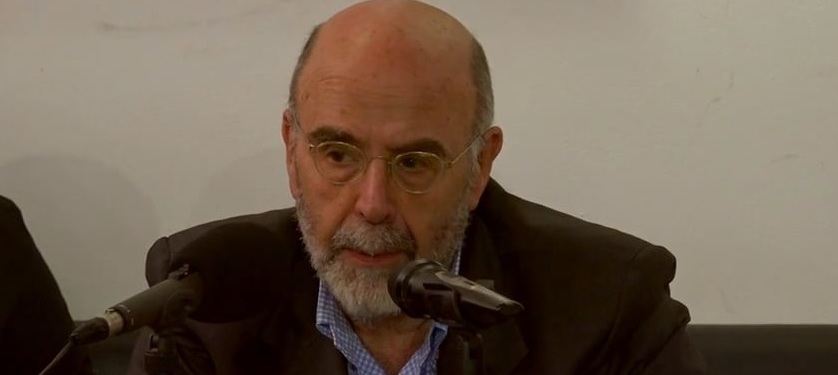

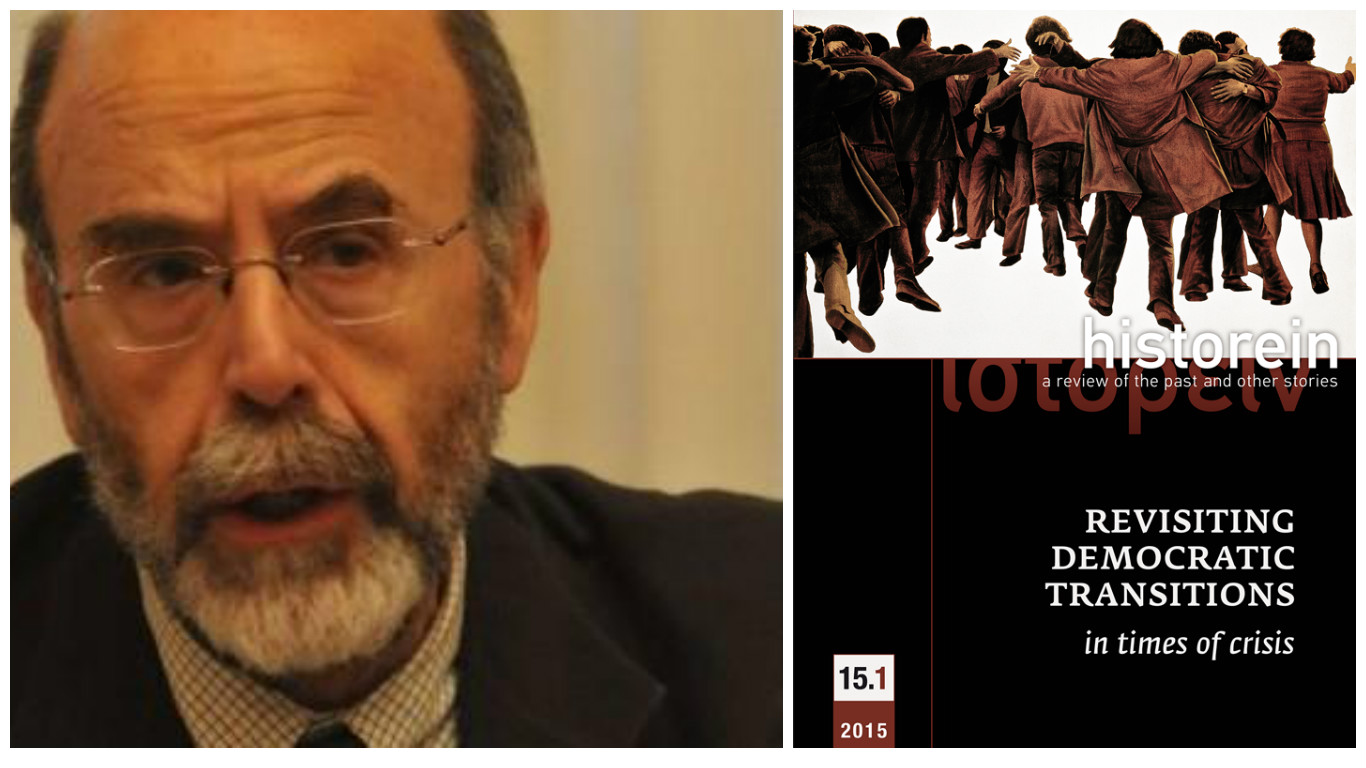

Antonis Liakos is a leading Greek historian, Professor Emeritus of Contemporary History and History of Historiography at the University of Athens and managing editor of the journal Historein.

He is head of Greece’s Committee for National and Social Dialogue for Education Reform. Inauguruated in December 2015, the activities of the Dialogue Committee included debates on a weekly basis, working sub-committees and special workshops (website in Greek: http://dialogos.minedu.gov.gr). A series of reforms are being planned for secondary education in Greece, after professor Liakos submitted the Commitee’s recommendations to the Ministry of Education on May 27 2016.

Professor Liakos spoke to Rethinking Greece* about education reforms and their political nature, education’s reproductive and redistributive role, welfare state, ‘demo-crisis‘ and the economic and political constraints for left-wing politics in Greece.

What are the main elements of the proposals recently submitted by the National and Social Committee for Education Reform?

The main points of our reform proposals refer to (1) the autonomy of schools and the adoption of a curriculum that is more flexible and friendly to the student, (b) a robust training programme for teachers throughout their career, (c) the creation of a two-year high school offering something similar to an IB (International Baccalaureate) type of programme, (d) changing the existing selection process and admission requirements for access to Higher Education, and (e) introducing research in secondary education. We also suggest boosting a digital turn in educational methodologies as well as the enhancement of audiovisual training tools. Generally speaking, there are problems caused specifically by the crisis as well as pre-existing problems of a long-term nature.

Historically speaking, educational reforms in Greece have been strongly politicized. How do the Committee’s proposals address political and social issues raised by the current crisis?

It is obvious that our education reform proposals are of a political nature. As a Committee, we insist on strengthening the public education system (because we are) convinced that its role is to reduce social inequalities. We should be able to provide high quality public education for the many, for those socially and economically vulnerable. To this end, we have suggested the introduction of a network of high quality schools in the most deprived areas of the country.

One of the most politicized issues was the implementation of a system for the evaluation of teachers. In order to smooth the way for specific policies, previous governments had systematically portrayed teachers as lazy and incompetent, while their evaluation was connected to occasional student occupations. But what they actually achieved was to discredit any attempt of creating an evaluation system and even to demonize the word “evaluation”. We are bringing back the teachers’ evaluation issue, introducing evaluation elements through a different perspective: teachers’ lifelong education, the introduction of goal-setting procedures by every school as well as the introduction of a National Curriculum and National Standards for Education.

Your proposals seem to offer a fertile ground for a progressive and more practical approach to education. How feasible do you consider their implementation and what may be the limitations posed by the crisis?

Your proposals seem to offer a fertile ground for a progressive and more practical approach to education. How feasible do you consider their implementation and what may be the limitations posed by the crisis?

The crisis has indeed cast a heavy shadow on the education system and has posed severe limitations on the government’s reform capacity. Teachers cannot be appointed where needed because there is no money and thus schools are forced to limit their classes to the basics. One third of the education budget has been cut. In order for a serious education reform to take place we need a certain level of financing along with the government’s capacity to legislate without preemptive interventions by the Quartet of international creditors.

You have stated that Greece, together with other European Mediterranean countries, has become an observatory for the great historical transformations of our time. How do education issues and the Committee’s proposals relate to this question?

When we talk about education, we usually refer to its role as a mechanism for social reproduction. Education reproduces social relations and this is why it is a policy area where ideological and political differences become prominent. The reproduction of social relations includes the reproduction of social hierarchies: the children of the educated become educated, whereas the children of the poor remain poor. In order to change that, and to ensure access to education for the poorest and the different, we need to have an education system of a redistributive character. This was what modern welfare states provided until recently and Greece’s education system prior to the crisis was on the process of integrating that principle.

The crisis changed all that, revealing trends of wider dynamics. Nowadays it is not only the content of the education that is contested, but above all its reproductive and redistributive role. Can education intervene in shaping society and social relations, or are new social relations and hierarchies reproduced beyond its influence? For example, can education ensure upward social mobility like it did in the past?

Education used to act as a centripetal force in society, and now it has been transformed into a kind of centrifugal force. Education used to be state-driven and centralized, while it absorbed and redirected educational practices. Now it has many centers that tend to escape from the state’s supervision; they are moving away from it, thus the emphasis of the private sector, in unschooling, in education vouchers etc., around which many neoliberal demands are articulated. In short, we are witnessing a retreat of the state from its role in the reproduction of society, as well as the creation of different hierarchies and social relations. However, these variations should not be interpreted only as options that express a rival policy and ideology. We also need to see how they form part of broader, complex and multifaceted historical changes.

Still, why do we insist on public education? Because these broader changes taking place at the moment tend to increase social inequalities and cultural differences, while what we want is to reduce inequalities, while respecting cultural differences. And there is something else I would like to point out: we believe that when cultural differences are combined with social inequalities, then the basic unity of society is ruptured. So we are supporting public education as a compensatory mechanism, as an antidote to these inequalities. But for that to happen, public education must change; it must be reformed in order to meet contemporary needs and conditions and to bring the school up to date with the major changes currently taking place in our societies.

Given that current developments in Greece and Europe have led to a crisis in democracy (‘demo-crisis’) do you think that they have also created the imaginaries to critically reflect on, challenge and collectively react against this crisis?

The elections of January 2015 showed that there was a strong reaction to demo-crisis. Their results indicated an attempt to bring “demos” (in Greek: [the common] people) back to the fore. What happened later, in the summer of 2015, was a ‘showdown’ between a conception of democracy based on the will of the people and the current institutional order of the European Union. It turned out that the second prevailed over the first. I don’t see this as a defeat but as a challenge to explore how the will of the people can be reconstituted in the existing framework and what this process may entail.

As a historian, I view this broader context as a wide field in which one should seek diverse solutions, rather than remain stuck in a full rejection or full compliance dilemma, which had been, to a large extent, the spirit of the previous period, where the ideological line was drawn between “pro-Memorandum” and “anti-Memorandum” political discourses. During that time, I often pointed out how inadequate this kind of politics was for the Left, although it proved instrumental in the Left’s rise to power.

Now, we must see what progressive reforms may mean under the current circumstances, and what can be defined as progressive and in favor of the many, the “demos”. It is not an easy task but such is the nature of historical dilemmas.

Is there, in your opinion, still room for progressive reforms in Greece, following the July 2015 compromise and the respective economic and political constraints?

Is there, in your opinion, still room for progressive reforms in Greece, following the July 2015 compromise and the respective economic and political constraints?

The limitations resulting from the July compromise, and the constraints imposed by the Institutions to provide loan disbursement are not only political and economic. Many of them are structural in nature and aim to change the social landscape of Greece, weaken the public sector and the role of collective decisions and increase the role of business interests and the market.

We have also seen cases were the changes imposed aim to just satisfy private interests. The concession of the former airport of Elliniko for a low price offered by a Greek oligarch (Latsis’ Lamda Development), and the pressure to grant even the very small share still controlled by the Greek state in the National Telephone Company to the German Telecom as a prerequisite for the latest loan disbursement is a clear example of this. The same holds for interferences of the so-called Institutions in legislation concerning issues of educational reform which didn’t entail a financial or economic aspect.

But still, there are progressive reforms to be implemented even within these “constraints”. Regarding education, one of them is the curriculum concerning religious courses and the relevant pressure exerted by the Greek – Orthodox Church. When the dialogue about education reform proposals started a high official explicitly told me that the religion curriculum should not be touched. And one can see that despite the fact that the curriculum in all subjects has been reduced, the religious curriculum remains as it was. It is obvious that in this case as well as in many others, there is significant margin for progressive reform.

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis and Athina Rossoglou

Read more: OECD: Greece – Overview of the education system; Educational reforms in Greece and a report from Berkeley; Analysis: Greece between democracy & demo-crisis; Europe’s Greek moment and Greece’s European moment