Christina Koulouri is Rector of the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences and Professor of history, specialized in Greek, Balkan and European History of 19th-20th centuries. She has studied at the History and Archeology Department of the University of Athens, the Sorbonne University (Paris I) and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris.

In 2010 she was a visiting researcher at the University of Sorbonne (Paris 1 –UMR IRICE), in 2017 Visiting Research Fellow at Princeton University and in June 2019 Visiting Fellow at the University of Regensburg (Germany). She has been awarded the Nikos Svoronos award “for outstanding achievement in the research of modern Greek historiography” (1994), the “Delphi” award of the International Olympic Academy (2012) and the Dimitrios Vikelas award of ISOH (International Society of Olympic Historians).

Professor Koulouri has published 8 books, 5 collective volumes and many articles in Greek, English and French, on issues such as history of nationalism, history of memory, history of sports and of the modern Olympic games, history of education and textbooks, reconciliation and peace education. Her latest book “Fustanellas and Togas. Historical Memory and National Identity in Greece, 1821-1930” (Φουστανέλες και χλαμύδες. Ιστορική μνήμη και εθνική ταυτότητα, 1821-1930, Athens, Alexandria, 2020) was awarded the Anagnostis Prize and the State Essay Prize.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Restoration of Democracy in Greece, Professor Koulouri spoke to Rethinking Greece* on the Metapolitefsi (the period of transition after the fall of the military junta in 1974) and its values; the social and cultural changes that occurred in Greece during that period; the importance of Greece’s EU membership; the political and social impact of the 2008 crisis; the ever-changing but still vivid memory of the Metapolitefsi, and finally on the achievements of the past and the challenges of the present and future for Greek Democracy.

Discussions on the 50th anniversary of the Restoration of Democracy in Greece cannot but examine the concept of the Metapolitefsi. How would you define Metapolitefsi, chronologically but also in terms of the values it embodies?

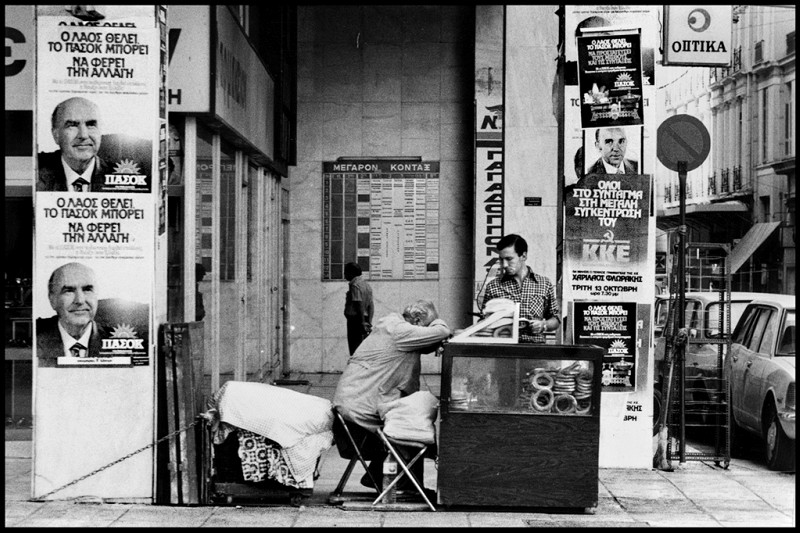

Metapolitefsi literally means regime change and in this sense, it is identified with the period 1974-1975, from the fall of the colonels’ regime to the adoption of the Constitution and the Trials of the Junta. However, the term has come to denote a broader period whose beginning is known but whose end is disputed. In my opinion, the period ended with the 2008 financial crisis, when the political system was reshuffled, and the achievements of the previous historical period were questioned. At the same time, we can identify political cleavages within the Metapolitefsi period, which correspond to domestic and international events. In terms of values, the Metapolitefsi is identified with the democratization of Greek society at all levels and therefore refers to the values associated with Democracy. Politically, this period is identified with PASOK, so it’s no coincidence that its ending also marked the political decline of PASOK, while the other major party, New Democracy, survived the political upheavals of the 2010s.

What were the most significant social and cultural changes in Greece during the Metapolitefsi period? How did Greek society evolve?

The euphoria following the collapse of the junta was reflected in every form of activity, characterized by what we could call a joy of life, especially during the optimistic 1980s. Democratization of family relations and education, changes in women’s status, and sexual liberation marked profound social changes, bolstered by Greece’s outward orientation, its entry into the EEC (later the EU), and rising living standards. In education, democratization meant changing the power relations governing the system and providing all young people with access to education, regardless of social or geographical background or gender. The publication of KLIK, the first lifestyle magazine in 1987, marked a shift towards conspicuous consumerism and a fantasy of social mobility. However, it wasn’t only social identities that were rearranged; since the 1990s Greek society enters a sort of identity crisis, which equally affected national identity, political identities as well as other collective identities. New collectives formed around cultural identities, such as those defined by traumatic memory (like the Pontians) or gender (like the LGBTQ+ communities), transcending the divide between “left” and “right,” and intersecting with the political crisis post-2010.

How did international events and global geopolitical developments affect the course of the Metapolitefsi in Greece?

A small country in Southeast Europe like Greece is inevitably influenced by international developments at all levels and is less resilient to global shocks. The end of the Cold War found Greece in the Western bloc, avoiding thus the dramatic transformations of Eastern bloc countries, but still affected the country in two ways: firstly, by neighboring Balkan countries’ aspirations to join organizations like NATO and the EU, and secondly, by a massive wave of economic migration to Greece. In the first case, issues like the new Macedonian question over the name of (now) North Macedonia, Kosovo’s independence, and relations with Albania posed many challenges. The so called name issue, in particular, plagued Greek foreign policy for decades and wasted precious resources, while domestically it fueled conservative reactions, exacerbated by the immigration wave. Racist rhetoric and xenophobic violence strengthened the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, and although its parliamentary representation was curtailed following its trial, far-right and fascist ideologies survive, subtly infiltrating other areas. As long as wars rage nearby, peace remains precarious both externally and internally.

What was the impact of Greece’s EU membership on the country’s course? How has the Europe-Greece relationship transformed over these decades?

Greece’s EU membership has been pivotal in many respects. Joining the EEC in 1980, soon after the transition to democracy and following Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus, was seen as a guarantee of political stability. The EU set specific requirements and conditions for Greece’s membership, leading to many institutional adjustments; it also offered economic support for development projects (the “Delors packages”, the Community Support Frameworks etc). Moreover, European integration offered Greece significant advantages, ranging from the right of free movement in other EU countries without many formalities and foreign currency exchange, to the country’s participation in shaping supranational European policies. However, these benefits were questioned when the financial crisis struck in 2008 and during the bleak 2010s. Greece’s relationship with Europe was tested by austerity policies and memoranda, increasing Euroscepticism. The 2015 referendum saw 38.69% in favour of the “we are staying in Europe” supporters, as opposed to 61.31% against. This result, however, should not be seen as an expression of a genuine desire to sever ties with Europe but as a protest vote against the severe austerity measures imposed and the dramatic increase in poverty.

How did the 2008 economic crisis affect Greek democracy and political stability? Do you believe the political fallout from this period has been addressed?

The economic crisis facilitated the rise of the so-called “anti-systemic” votes at the expense of the two parties that governed during the Metapolitefsi, i.e., New Democracy, and PASOK. The June 2012 general elections marked the shakeup of the political system, with New Democracy getting 18.85% (down from 33.5%) and PASOK just 13.18% (down from 43.9% in 2009), while the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn entered parliament for the first time with 6.97% and 21 seats. Turmoil continued with the collapse of SYRIZA in the May 2023 elections, a party that absorbed the social protests of the crisis era but was “punished” for failing voters’ initial expectations. The real casualty of the crisis seems to be the two-party system that characterized the era of the Metapolitefsi. This can be evidenced by the current political scene where we have a strong leading party and a fragmented opposition; however, the political tradition of two opposing “camps” has not disappeared. It remains to be seen if the center-left will regroup or if the parties to the right of New Democracy will be further strengthened.

How has the memory and significance of the Metapolitefsi changed over time and across generations? Do you believe the historical memory of this period still plays a role in contemporary Greek politics?

As long as we believe that the era of the Metapolitefsi has not yet ended and for lack of a new term for the period that has succeeded it (in the event that we believe that the Metapolitefsi is ineed over), talking about collective memory is challenging. It’s about the memory of specific events (e.g., the Athens Polytechnic uprising in 1973, the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, PASOK’s victory in 1981, joining the euro in 2001, the 2015 referendum etc) recalled by those who experienced them because they define their identity. And since we are talking about different generations with vastly different historical experiences, memories differ, and construct different identities. Given that the “Polytechnic generation” that ruled the country during the Metapolitefsi, is considered responsible for the financial crisis, younger generations who found themselves in the midst of the crisis hold a rather negative historical memory of the period. However, the negative assessment of the era is not only a generational issue, but also a matter of political identity. Criticism of the era’s policies mainly stems from right-wing positions, as a reaction against what was considered the ideological dominance of the Left. Indeed, the Metapolitefsi as a historical period has been invested with specific meanings and refers to particular values associated with the Left. Hence, the memory of the Metapolitefsi lives on, through political ideologies and prominent figures in politics and culture.

Looking back, what do you consider the greatest achievements and weaknesses of Greek democracy over the last 50 years? What challenges do you think it will face in the future?

The greatest achievement of Greek democracy is that is has endured. This is no small feat for a country with a history of military interventions in politics, authoritarian deviations, dictatorships, civil wars, and regime changes. It’s also notable that democracy withstood the shocks of the economic and political crisis and the threat of far-right extremism. However, issues of transparency, accountability, corruption, and clientelism persist. Recent tragic events highlighted the state’s operational gaps. Democracy faces numerous challenges, present and future. Democracy is not a given; it is vulnerable to unforeseen threats—both domestic and international—making protective mechanisms and a cultivated democratic consciousness among citizens crucial.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi, Translation: Magda Hatzopoulou

Read also from Greek News Agenda

TAGS: GREECE IN THE EU | METAPOLITEFSI | MODERN GREEK HISTORY