Despina Lalaki is a sociologist who works in the areas of historical and cultural sociology, social theory and Modern Greek Studies. She is particularly interested in long-term social and cultural changes, the changing modes of consciousness, the history of the state and its ideological and cultural foundations, the role of the intellectuals. Parts of her research results have been published in The Journal of Historical Sociology and in Hesperia, The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Despina Lalaki received her Ph.D. in Comparative Historical Sociology from The New School University in New York. She has also studied History of Art and Architecture at SUNY-Binghamton University and Archaeology and Art History at the University of Athens, Greece. She has taught at New York University and the A.S. Onassis Program in Hellenic Studies. She currently teaches at CUNY-The New York City College of Technology.

She also writes for newspapers and magazines and contributes commentary to radio, TV programs and social media on current developments in Greece (Greece in Crisis: An Interview with Despina Lalaki– Boston Occupier, The Greek crisis as racketeering-Al Jazeera).

Despina Lalaki spoke with Rethinking Greece* about the image of antiquity in the Greek national narrative and identity, Greek archaeology and the idea of Hellas, the transformations the notion of Hellenism underwent during the twentieth century, the cross-cultural fertilization between Greece and the United States, Hellenism vis-à-vis modernization and cold war politics, Greece’s international image campaigns and heritage industry, the “cradle of democracy” as post WWII American and European construct, as well as the political imperative for social sciences to offer critical and practical reappraisal of the EU center-periphery relationship.

Archaeological discourse seems to hold a central place in the Greek national narrative and identity. In what terms can/should archaeologists and social scientists review such issues in the current context?

Nations are made of the stuff that archaeology produces. Archaeology itself would look very different, had it not been born in the age of nationalism. After having for a long time been considered an aid-science to history, archeology was quickly incorporated in the national agenda in search of origins; ethnic and racial groups were believed to be associated with specific material cultures. In the case of Greece, archaeology provided the material evidences, the histories and genealogies that connected the Modern Greek state with a past already sanctified in the political and cultural imagination of the West. Most importantly, it helped to create a unified and unifying symbolic language that was terribly important for the cultural integration of the modern nation-state and the formation of a national identity. Upon the destruction of older social structures, classical antiquity -with the help of archaeology- provided the necessary means for national integration, through the creation of a new type of consciousness.

The Modern Greek state, not unlike other nation-states, found in culture a way to establish the loyalty and cooperation of the new political entity’s members. As Hobsbawm has suggested, it was in connection with the emergence of mass politics that rulers and middle-class observers rediscovered the importance of “irrational” elements in the life of human collectivities, in order to maintain the social fabric and the social order. In this top-down process, which worked well beyond merely enabling political consolidation and domination, archaeologists played a decisive role in articulating an image of antiquity that is so central to the subjective idea of the nation. What we could identify as “professional” and “policy archaeology” worked hand in hand with the Modern Greek state to develop a body of knowledge and public policies that sanctified classical antiquity – often to the detriment of other periods. They promoted a Helleno-centric reading of Modern Greek history, while sharing in western discourses about the preeminence of western civilization. I think it is important that social scientists and archaeologists engage with what we could call “critical” and what is known as “public archaeology,” if we are interested in re-examining the foundational premises of our fields of knowledge, while also engaging with a broader audience. It is my belief that the democratization of knowledge on the field can only come about through an intense dialogue among these various aspects of archaeological labor. Certainly, archaeology in Greece has been slowly opening up to various critical approaches. Institutional efforts such as the Archaeological Dialogues – an initiative by Professor Yannis Hamilakis – that have already been warmly embraced by the academic community but also the general public, constitute a move in such a direction.

How has the notion of Hellenism been defined in the 18th / 19st centuries? Which were the historical circumstances that made it necessary and to which political needs did it respond? What was the role of archaeology in its shaping?

How has the notion of Hellenism been defined in the 18th / 19st centuries? Which were the historical circumstances that made it necessary and to which political needs did it respond? What was the role of archaeology in its shaping?

Historical trajectories and origins matter. The continental beginnings of Greek archaeology had their roots in Hellenism – this convoluted set of meanings and symbolic codes which allude to the importance of ancient heritage for western civilization. Born at the intersection of Enlightenment, Romanticism and the Philhellenic frenzy of the early 19th century, Hellenism largely expressed European fantasies about the revival of Classical Greece through a national liberation movement. It provided Greek archaeology with a horizon of affect and meaning, the cultural landscape against which institutions and individual actions are shaped and from which they draw their significance. Antiquities provided the ‘hard evidence’ and material expression of the European nostalgia for an idealized past, emancipated from the Roman and Catholic traditions and ample of symbolisms for their ideological struggles against the old regime of ecclesiastical and secular authority. Subsequently, the modern Greek state, established in 1830, fully engaged in the institutionalization of archaeological practices and appropriated Hellenism to articulate a modern Greek identity as the progenitor of western civilization, while rupturing ties with its Ottoman past and hesitantly fitting the Byzantine Orthodox tradition into a linear national narrative.

Critical approaches to the history of Greek archaeology (rooted in multiple intellectual traditions such as post-structuralism, Marxism and critical theory, and the sociology of scientific knowledge) have largely sought to understand it as reflection and mediation of larger sociopolitical interests and ideologies, its results often harnessed for identifiable political ends. Yet, it is important not to reduce Greek archaeology to the mirror image of these interests and ideologies. Furthermore, provided the history of the field, one can go beyond the nation and national ideologies as the starting point of analysis. I favor an approach that prioritizes civilization as a historical and analytical category that focuses on the interplay between various national institutions and agents in the field, its relational dynamics and the shifting networks of interdependent actors and institutions. Following agents of the field around, trying to establish causal relations, and recreating the historical record, but also understanding the meanings and ideas produced as a result of ongoing struggles and interactions, may better help us to account for the full spectrum of debates taking place over long periods of time or archeology´s impact on the configuration of larger cultural ‘products,’ such as that of western civilization.

Did the notion of Hellenism remain analytically relevant in the twentieth century? How were post-war American visions of development and modernization related to Modern Greek imaginaries? What has been the role of the Greek-American Diaspora in that context?

The social history of Hellenism, while significantly transformed, continued to unravel well beyond the nineteenth century in the intersection of state-building, trans-national politics and market networks. It is important to remember that state-building in Greece has never been a Greek matter alone, since the Greek cultural heritage continues to be of great symbolic, political as well as economic significance. During the last century the idea of Hellas changed from being employed as a critique of the effects of modern civilization – primarily informed by German visions of self-improvement, disinterested Wissenschaft and cultural reform – to an expression of instrumental rationality, cultural commodification and liberal democracy. Post World War I aspirations, for instance, of an international civil society expanding through the means of culture and the free market, as conceived by influential parts of American society, made considerable inroads in Greece, building upon the tremendous symbolic capital of antiquity.

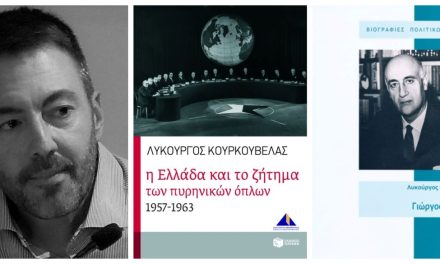

Beyond the influences in popular culture we have paid very little, if any, attention to the processes of trans-valuation and cross-cultural fertilization between Greece and the United States, despite the prominent role the latter has had in the most recent political and social history of the country. The interest that the United States has taken in Greece, especially following World War II, has not been solely on the level of “high politics” or economics, because the idea of Hellas has had a strong hold on the relationship between the two states. In post war Greece, the American policies of economic liberalism and social democracy – a kind of New Deal world policy – for full employment, modernization of ruined economies, and communist containment invested symbolically as well as in economic terms in Hellenism, while radically transforming it in the process. The rationalization and promotion of the ancient cultural heritage, primarily via tourism, was meant to lead to economic and consequently political stability, modernization and therefore the elimination of the communist threat. Hellenism, well removed from the romantic visions of the nineteenth century, was now reimagined in very pragmatic terms as the country’s propeller into the future.

The work of American educational and research institutions, cultural foundations, philanthropic agencies and organizations in Greece has been greatly understudied. During the war, complex networks of scholars and academics, administrators, and old as well as emerging economic and cultural elites – including the Greek-American diaspora – emerged in response to the urgency of the times. Subsequently, these networks further expanded to assist with the reconstruction of the country and its ideological realignment. Institutions such as the American School of Classical Studies, for instance, which I have closely studied, and its staff of archaeologists became, rather inadvertently, central nodes in these networks, while the Greek-American diaspora, especially new wealth entrepreneurs, constituted almost a natural pool of resources. So, regarding the contribution of the Greek-American diaspora in the efforts for Greece’s post-war reconstruction there is still great room for in-depth research.

How did democracy become part of the “we images” and ‘‘we-feelings’ of the Modern Greek identity? How do they relate to American and European perceptions of democracy?

“The cradle of democracy” – the way we perceive our identity as treasurers of western civilization’s political foundations – is largely a Cold War construct that carries the imprints of modernization theory and European hegemonic social hierarchies. Most importantly, a whole set of ideas associated with this construct, conditions and constrains our cultural dispositions and political imagination to this day.

The struggle for democracy defined the twentieth century; democratic frameworks were really secured only in the wake of the Second World War. Yet, there was nothing natural or inevitable about democracy in Europe, or anywhere else for that matter, as Geoff Eley explains. It did require conflict and violent confrontations. It was not the result of a natural process or economic prosperity, nor the inevitable byproduct of individualism or the market. It was rather the outcome of collective and mass mobilizations on a trans-national scale. In Greece, however, there was something inevitable about democracy. The British military intervention against the National Liberation Front, (EAM), in favor of the old regime, the subsequent heavy-handed American political and economic interference and, later on, the admittance into the European family were events directly related to broader socioeconomic and geopolitical configurations which, however, carried a strong ideological imprint; the cradle of western civilization and democracy could not be abandoned to communism or the influence of a semi-European culture.

While self-determination and equality were the basis of the republican strand of Greek nationalism, democracy nevertheless was not prominently featured in the state’s representational agenda until after the end of the Second World War, when the struggle between the old political establishment and the communist insurgency was still raging. The term of Democracy itself, a rather empty signifier at the time, became a rallying cry against communism and the Left more broadly. In the process, Hellenism was further employed to shape new ontological and epistemological distinctions between the Democratic West and the Communist East, normalizing the postwar political and economic status quo and offering legitimacy, first to American hegemony and later on, to the European integration project.

It seems that Greece’s international tourism and heritage industry as well as its international image campaigns have largely been based on Ancient Greece. Which are the underlying ideological parameters?

It seems that Greece’s international tourism and heritage industry as well as its international image campaigns have largely been based on Ancient Greece. Which are the underlying ideological parameters?

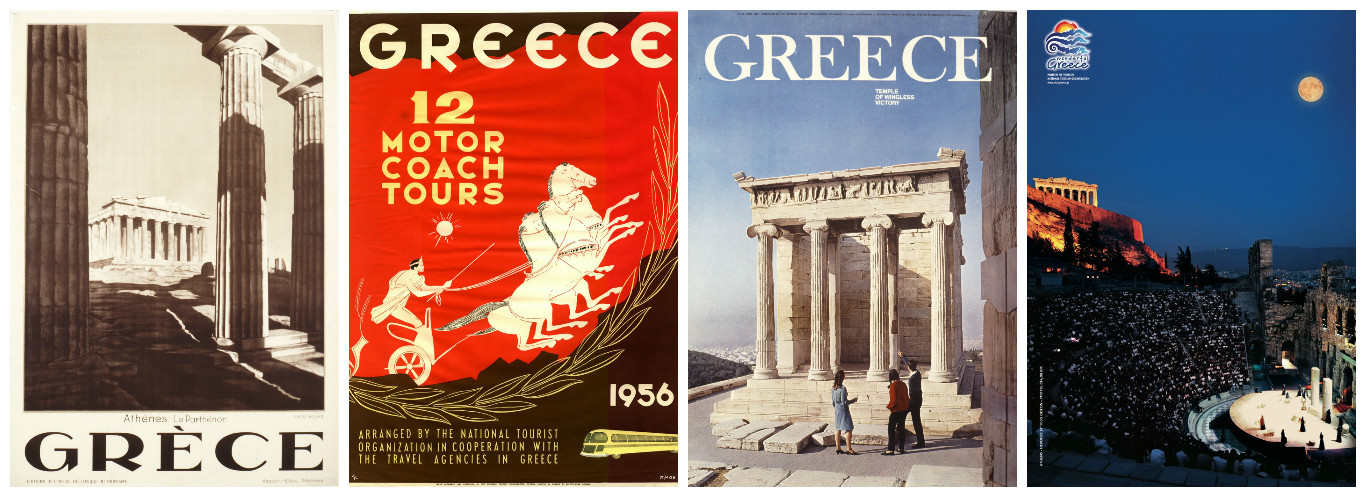

The image of Greece as the cradle of Western civilization and democracy was consolidated not at the excavation site, the museum, or even the lecture hall, but in the tourist campaigns of the Greek Organization of Tourism (EOT), in the brochures and advertisements of travel agencies, and on the Hollywood big screen. Tourism, as a mechanism of representation, has had a profound effect on the process of objectification of national collective consciousness.

Tourism can be defined as a particular species of industry which, more than any other form of capitalist industry, sells not only commodities, but also worlds of meaning and experience, marketed so as to create very specific and at the same time, highly idealized representations of places, cultures, nature and people. The ideological power of such an agency was early on identified by Ioannis Metaxas, who placed the post of Undersecretary of Press and Tourism under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. EOT, established later on, could be identified as one of the most powerful agents in the construction of national identity in the postwar Greece. Until the 1980s, Greece was primarily marketed to the American consumers, initially as the ‘cradle of Western civilization,’ placing emphasis on its ancient cultural heritage and increasingly as a summer vacation destination and a retreat from the hustle and bustle of modern civilization. As soon as the two oil crises had run their course and European consumers gained buying power, Greece, the ‘cultural park of Europe’ as UNESCO would describe the country, would start targeting the European market for consumers. “Greece – The Europeans’ European Vacation,” as EOT advertised in 1988, was marketed as the preferred choice by smart travelers, while gradually shifting from a mass tourism policy to a more locally-integrated and less invasive tourist development model.

Tourism is a way of representing the world not merely to others but to ourselves as well. Time and again Greece has been promoted as the destination where cultural sophistication meets a landscape untouched by modernization, the land where Western civilization took its first steps and the inhabitants maintain something of a more carefree and simple past. Either directly and programmatically through assertion, or indirectly by implication, we have been reproducing -and in the process internalizing- narratives that date back to the nineteenth century, while suffering the effects of the tension between the much celebrated ancient ancestors and the indolent descendants.

According to some scholars, the current crisis revealed Europe’s ‘crypto-colonialist’ traits. What can social sciences do for a critical / practical reappraisal of the relation between European core and European periphery?

According to some scholars, the current crisis revealed Europe’s ‘crypto-colonialist’ traits. What can social sciences do for a critical / practical reappraisal of the relation between European core and European periphery?

These scholars, notably anthropologist Michael Herzfeld, who first introduced the term, correctly suggest that massive economic dependence has curtailed the political independence of the Modern Greek state from its inception. Modern Greek national culture was also largely fashioned along the lines of western fantasies and expectations, rendering Modern Greeks wanting in the process. In nineteenth century terms, one could describe this relationship as “crypto-colonialist.” At this historical junction, however, I think it is important to talk about neoliberalism as opposed to colonialism, or even crypto-colonialism, if we wish to better understand the evolution of the European project during the last thirty years or so. Despite the constitutive role of colonialism in the development of mechanisms that supported global capitalism, colonialism and neoliberal capitalism are politically distinct projects with significantly different characteristics.

The current crisis laid bare the anti-democratic foundations of the European Union, its anti-internationalism, racism and imperial nostalgia. What is also important to note, is that the inability to perceive alternative modes of political and social organization beyond the onslaughts of neoliberalism under the mantle of European integration, is intrinsically connected and closely intertwined with identities that are far from being as immanent or as primordial as they appear. They are, instead, socially and historically grounded on configurations and events following the Second World War; they constitute responses to the European Cold War order, fierce anti-communism, transatlantic militarism and free market economy – albeit moderated by a welfare state, destined to succumb to the onslaughts of neoliberal capitalism. Austerity Europe would not have been possible without a set of narratives capitalizing on misrecognized cultural cleavages between the European North and South and invented, long internalized genealogies. In the case of Greece, the charter myth of Hellenism has been re-deployed as a legitimizing ideology for the bourgeois Greek state as well as the western European establishment steering, once again, Greek democracy’s course.

The political imperative for social sciences to offer critical, but also practical reappraisal of the EU center-periphery relationship, differs for each scholarly field. Specifically for comparative historical sociology, the perspective from which I talk, I argue that the imperative is not to provide direct answers to private or state-administrative queries related to the crisis, but analyses rich-in-detail and interpretation, causal explanations from a macro point of view as well as parallel investigations and comparisons. If the objective is to intervene and fight the crisis that appears to disrupt long established social structures, institutions and organizations, or to change those structures, it is imperative that we have a deeper understanding of the complex social processes in which this crisis is embedded. Historical sociology is ideally positioned to seek causal relationships behind important social phenomena or to provide explanation regarding issues such as the democratic deficit of the European Union, the rise or decline of labor organizing or the social origins of fascism, for instance. In the process, engagement with various perspectives in the European periphery, might lead to methodological innovation and a historical sociology that is both richer in theory and empirical evidence.

It is, of course, the case that offering in-depth objective historical and sociological research and analysis may not be sufficient, if social change is to be a part of social sciences’ objective. It is important, I think, that we carefully reconsider our relations to the centers of power, as well as what our audiences are. We should bear in mind that our scholarly practices have a strong social dimension, while our scholarly work is accountable not only to peer review but also to the publics it serves.

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis and Athina Rossoglou

Watch Despina Lalaki talk at Brown University / Watson Institute Conference (Crash Culture: Humanities Engagements with Economic Crisis, April 2016 – from: 00:58:30):

TAGS: ARCHEOLOGY | HISTORY