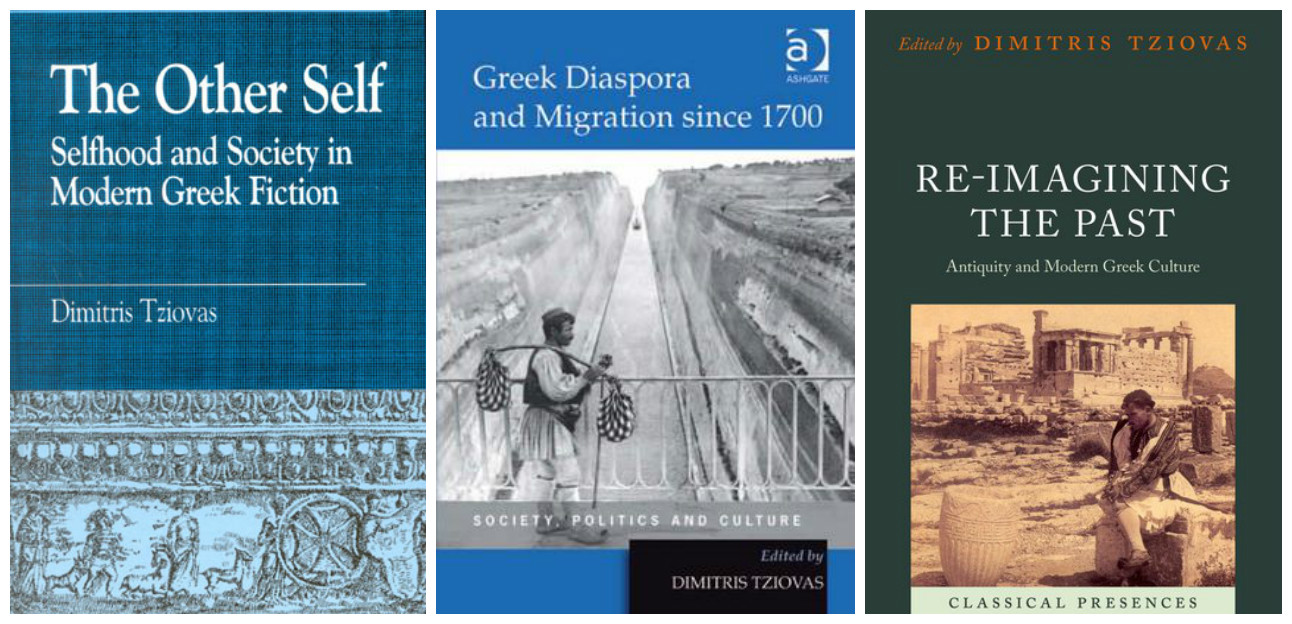

Dimitris Tziovas is Professor of Modern Greek Studies at the University of Birmingham, UK and General Editor of Birmingham Modern Greek Translations. His publications include The Other Self: Selfhood and Society in Modern Greek Fiction (2003), Greek Diaspora and Migration since 1700 (Editor, 2009), The Myth of the Generation of the Thirties: Modernity, Greekness and Cultural Ideology (in Greek: Ο μύθος της γενιάς του Τριάντα, Νεοτερικότητα, ελληνικότητα και πολιτισμική ιδεολογία, 2011), and Re-imagining the Past: Greek Antiquity and Modern Greek Culture (Editor, 2014).

He is also a regular contributor of commentaries regarding various aspects of Neohellenism frequently focusing on the “international image of Greece” theme in Το Βήμα daily. He has been recipient (2012) of the Diavazo award for the best Critical Writing Prize.

Professor Tziovas currently leads a networking project on ‘The cultural politics of the Greek crisis’ (September 2014 – August 2016) which aims to stimulate debate among academics, research students, journalists, artists and writers on the implications of the economic crisis for Greek culture and identity.

Dimitris Tziovas spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the theory of cultural dualism, Greece’s cultural gravitas, the narratives on the Greek crisis and the reinvention of Modern Greek Studies:

You have recently (Η γοητεία των σχημάτων, Το Βήμα, 21.2.2016) referred to Patric Leigh Fermor’s “Helleno-Romaic Dilemma”, the “perpetual conflict between the glory that had been Athens and the sorrow that was Byzantium”. Is this narrative still relevant to the western imagination of Greece and the self-understanding of the Greeks?

One of the most enduring and influential interpretations of Greek cultural and political developments since independence is that of cultural dualism, based on the assumption that two opposing trends or forces are vying for supremacy. The traditional and pre-modern segmentary society, broadly associated with the East, is contrasted to the civil society and western models of administration (which in the case of Greece were championed by diaspora and modernising elites). Cultural and political dualism, in its various forms, has emerged as the dominant model of and for the post-junta period but also for the earlier history of Greece. It has been adopted in different forms by anthropologists, political scientists and historians and has framed the discussions of political and cultural developments in Greece. This dualism continues to inform the way Greek culture is analysed and Greece is presented as poised between a troubled tradition and a desired modernity. The resilience of the dualist approach as a useful analytical tool has something to do with the fact that the notion of modernisation, in the sense of ‘catching up with Europe’, has increasingly entered debates on national identity as representing a break with the vestiges of the country’s ‘Ottoman’ and ‘oriental’ past.

Though the theory of cultural dualism has been employed widely in the recent years, it obscures ambivalence and hybridisation. This ambivalence has led to the treatment of the state as both a source of secure employment (a survival of the earlier clientelist mentality) and as an adversary (a result of the rising of the anti-systemic discourse of the underdog culture). It seems to me that during the crisis this ambivalent attitude towards the state has been extended to the EU, leading to its being considered as both saviour and enemy. The crisis simultaneously strengthened and profoundly undermined the authority of the modernising discourse. It also exposed the inadequacies of cultural dualism as an interpretive methodology and questioned its evaluative implications and political uses. Greeks, for example, may simultaneously admire and hate anything associated with modern Europe. They aspire to be Western while at the same time looking down on Westerners, saying: ‘when we were building the Parthenon, Northern Europeans were living in the trees’ in the same way as they treat their ‘homeland’ as a ‘whore’ and a ‘Madonna’.

Does the “Generation of the Thirties” and its modernism still inform contemporary Greek social and political consciousness? In what ways should we read / view those authors and painters today?

Does the “Generation of the Thirties” and its modernism still inform contemporary Greek social and political consciousness? In what ways should we read / view those authors and painters today?Apart from their contribution to art and literature the so-called generation of the Thirties foregrounded the issue of cultural identity seen from a new perspective. To put it briefly, until the 1930s Greece was torn between East and West, but following the Asia Minor Disaster Greece abandoned its Eastern aspirations and has tried to define its identity primarily as part of the West and in an extrovert/competitive manner, exploring its modern distinctiveness and highlighting it in contrast to the ancient legacy and perceptions of western supremacy. This is summed up by Yorgos Theotokas in 1929 when he lamented that ‘the weakness of Modern Greek literature is not that it has received many influences, but that it has given nothing back’. This attempt at self-definition has not been an easy task and has been constantly debated over the years.

According to social anthropologist Michael Herzfeld “Western moralism about alleged Greek “corruption,” “laziness,” and “irresponsibility” occludes the West’s own complicity in generating these attitudes”. Would you like to comment on this?

Many Westerners have indeed revived their stereotypes about the lazy, feckless Greeks and argued that the idea that Greece’s troubles are externally imposed, which allows many Greeks to depict themselves as blameless. On the other hand, some Greeks developed a sense of victimhood, often reinforced by references to history. The combination of victimhood and conspiracy theories is a symptom of a national narcissism and reactivates feelings of ethnocentrism or even racism, pointing to the importance of cultural attitudes in coping with the crisis and the role of the media in promoting such responses.

It could be said that Greeks continue to see modern Europe in nineteenth-century terms, as when Delacroix depicted the ‘Massacre of Chios’ and Byron, Shelley, François-René de Chateaubriand and Victor Hugo expressed their philhellenic feelings. Philhellenism has become an integral part of the modern Greek identity, and the crisis has enhanced a sentimental and romanticized approach to international relations. European leaders are judged by their philhellenism, and the purported statement by the former French president Valéry Giscard d’ Estaing that ‘the descendants of Plato cannot play in the second league’ has received wide publicity in the Greek media.

The crisis has also sparked off a debate about Europe and a rethinking of its cultural values, politics and orientation. Harking back to an elusive ideal of European humanism, which has been gradually eroded due to neo-liberal austerity and the shrinking of the welfare state, it is claimed that the crisis precipitated the clash of two visions of Europe: an older and rather idealized Europe of human solidarity and democratic values, and that of the technocrats and managers, leading to social exclusion and restricted access to education. This clash suggests that for many Greeks Europe is gradually moving away from past ideals, and its future unity and identity is increasingly in doubt. The past humanist aspiration of an integrated Europe seems to be contrasted with its uncertain future undermined by nationalism and the South–North divide.

References in the international media to the classical Greek past are often deployed in a condescending way. What does this attitude mean for the international perception of Greece?

During the crisis many foreign commentators and journalists have used ancient Greek mythology or imagery in order to illustrate the dire economic situation of the country and the predicament of its people. It has been claimed that ancient myths lend context to the swirl of acrimony and austerity, bailouts and brinkmanship, and have plenty to say about hubris and ruin, order and chaos, boom and bust. It is clear that Greek antiquity functions as a crucial symbolic resource in the annotation of modern Greece. It is a trope through which the western media, and by extension the West, approach and portray Greece in crisis. The ‘glorious’ ancient Greece is contrasted with modernity while the ancient past is set against the ‘failures’ of modernity with a sense of irony. Antiquity is used to exclude modern Greeks from the discourse of Hellenic civility, to constitute them as the inefficient ‘other’ and to disengage the country’s mythic status from its precarious present.

The Greek crisis is translated against a Hellenic ideal, or even against an antique stereotype. This frequent reference to the ancient Greek world in relation to the crisis is rather surprising considering that in other areas the ties between classical and modern Greece are presented as tenuous. Though the notion of a cultural continuity has been promoted by the Greeks, it has been consistently resisted by many westerners. It resurfaces only in periods of crisis and for the purposes of unfavourable reporting or commentary. Ancient myths might offer journalists and commentators the opportunity to illustrate their stories and perhaps make them more appealing to their audiences, but this deceptive connection aims to draw an implicit criticism by contrasting ancient glory with contemporary failures. In spite the fact that Greece represents around 3 per cent of the European economy, its cultural gravitas in the European project is much greater than its economic weight. Another country of similar size might have been forced to leave the eurozone, but Greece still occupies a special place in the European imaginary.

Greece has been haunted for 6 years now by the “pro-memorandum” vs “anti-memorandum” narratives and the associated finger-pointing in the public sphere. Is there an alternative to this mode of thinking and debating?

The narratives on the Greek crisis follow the division of the Greek people into supporters and opponents of the bailout agreement. What is interesting is that both narratives have a time dimension in the sense that they see the crisis either as a relatively synchronic event or as a culmination of a long process of incompetence and state failure. Between these narrative polarities, there is a third narrative that attempts to apportion blame between Greek politicians and voters and Greece’s European partners and the EU institutions. Along with the inadequacies of the Greek administration, it is acknowledged that the crisis brought to the surface the imperfections of the EU. The crisis has made many talk about a new ‘narrative’ for Greece, a departure from the failed practices of the past, a kind of national catharsis and replenishment. It has also induced Greek society to rethink its values, to revisit its founding myths and to re-examine its earlier certainties. This involves to a certain extent a narrativization of the traumas of history, an interrogation of past practices and a critical searching for what went wrong, using the past as a guide. As a result the past is destabilized and at the same time acts as a source of strength.

“The cultural politics of the Greek crisis” project runs its 3rd and final workshop (University of Oxford, 17.3.2016). What is the significance of such initiatives and can they be useful for the better understanding of Greece by international publics?

“The cultural politics of the Greek crisis” project runs its 3rd and final workshop (University of Oxford, 17.3.2016). What is the significance of such initiatives and can they be useful for the better understanding of Greece by international publics?First of all it is significant that this project, hosted by the University of Birmingham, has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Council of the UK and is the first of its kind. A range of scholars, artists, critics and students contributed to the three workshops (London, Birmingham and Oxford), which were well attended. The project through its workshops and the contributions to its website has explored the impact of the crisis on various areas of Greek cultural life such as book production, literature, cinema, museums, media, photography, heritage, festivals, street art and attitudes to the past. We also developed contacts with other research projects, academics, artists and cultural agents in three continents and shared with them ideas about the cultural impact of the economic crisis and the politics of austerity. Using a questionnaire available on the project’s website we have also surveyed the attitudes of a number of young Greek professionals who have left the country to seek employment abroad and the challenges they faced in their host environment. Respondents to the questionnaire included diaspora Greeks from the UK and other European countries as well as Australia.

You have once stressed that “the history of Modern Greek Studies is a story of… emancipation from the classical ideal and from its ethnographic idealization as exotic land…”. What can Modern Greek Studies teach us concerning Greece’s public diplomacy and international communication in general, especially in view of the current crisis?

In an article (The study of modern Greece in a changing world: fading allure or potential for reinvention?) to be published in the next issue (April 2016) of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies I argue that the discipline seems likely to move from Modern Greek Studies as we know it today to a range of diversified discourses and studies on Greece emerging from different areas of academia. Archaeologists, historians, political scientists, film, media and drama scholars have built up a corpus of studies on Greece which could help researchers to study the country or to include it in comparative studies without knowing Greek. This in turn raises another question: what makes a subject ‘trendy’ and brings a country to scholarly attention? In the past it was its alluring traditionalism or ‘orientalism’ that made Greece a charming country in the eyes of foreign visitors and scholars, or else the image of a nation fighting against conquerors, invaders or oppressive regimes.

Exoticism and resistance gave way to conflicts and crises, which helped to maintain Greece at the forefront of scholarly attention. For example, the disintegration of Yugoslavia brought the Balkans to the fore, the turbulent decade of the 1940s and the challenge of Europeanization produced a decent scholarly output, while the economic crisis in Greece has also generated a good deal of debate and numerous publications. The growth of studies on Greek-Turkish relations and Cyprus reinforce the view that areas of conflict foster academic scholarship and attract international interest. Are conflicts and crises sufficient to make Modern Greek Studies attractive in the twentieth-first century? It seems that we are moving towards post-national and trans-cultural studies covering wider areas or themes across several countries rather than focusing on national cultures or histories. Broader themes or questions are given priority while secondary importance is assigned to case studies or paradigms in illustrating these themes and tackling the questions.

*Interview by Nikolas Nenedakis

“The cultural politics of the Greek crisis”, Workshop 1: Greece: From Junta to Crisis, Session 2: Cultural dualisms (20.9.2014):