George Prevelakis is Professor Emeritus in Geopolitics at the Panthéon-Sorbonne University (Paris 1), Research Professor at CNRS (UMR Géographie-cités), Distinguished Visiting Professor at Hellenic American University and Archon of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. He specializes in European, Balkan and Eastern Mediterranean Geopolitics, in Diasporas and in Physical Planning. After leaving Greece in 1984, he has occupied teaching and research positions in Paris, Baltimore, Boston and London. During the academic years 2003-2005 he served as the Constantine Karamanlis Chair in Hellenic and Southeastern European Studies at the Fletcher School (Tufts university). He has served twice, in 2013-2015 and 2019-2023 as Greece’s Ambassador to the OECD.

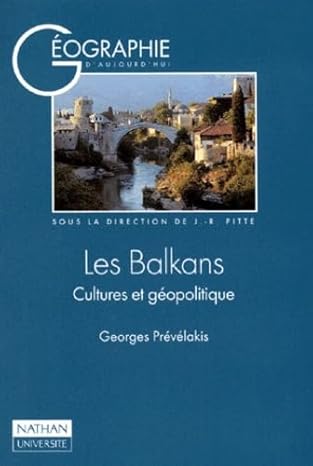

He has been active in international media and think tanks on questions related to Balkan security and Geopolitics and is a frequent op-ed contributor to the Athens dailies Kathimerini and Ta Nea. Among his latest publications are, “Pourquoi une nouvelle Entente balkanique?” (2010), “Who are we? Geopolitics of the Greek identity” (2017), “Wooden Walls” (“Ξύλινα Τείχη,” in Greek, 2020) and “In the OECD: Geopolitical Theory and Diplomatic Action” (2024).

In this interview with Rethinking Greece* professor Prevelakis explores the evolving landscape of geopolitics and its impact on international organizations, arguing that the era of globalization is receding, with non-economic factors like religion and geopolitical tensions regaining prominence. He advocates for a “new Western doctrine” that balances acknowledging Western contributions with historical reflection and cooperation. He highlights the growing importance of seas and oceans in economy and in geopolitical strategy and proposes that Europe embrace an “archipelago” model of interconnected entities linked by sea, pointing out that Greece could be playing a leading role in this future, due given its maritime geography, historical engagement with seafaring, and robust merchant marine. Professor Prevelakis also discusses demographic shifts as drivers of history and population geography as a significant long-term factor influencing the evolution of humankind. Finally, he argues that smaller nations like Greece can leverage multilateral organizations through bold strategies, an example of which is the establishment, during his tenure, of the OECD Population Center in Crete, as a critical institution to address global challenges related to population dynamics.

You have served two terms as the Ambassador of Greece to the OECD. In your book, “In the OECD: Geopolitical theory and diplomatic action” you highlight the importance of geopolitics in international relations. How does the primacy of geopolitics, and what you call the “revenge of history and politics” affect OECD’s mission and priorities?

There is a growing consensus among experts that the contemporary world is undergoing a period of profound transformation, precipitated by the election of Donald Trump but rooted in gradual developments over the preceding years. The post-Cold War era is coming to an end, giving way to a dramatic reversal of conditions and values.

The previous era was characterized by an increasing openness to global circulation. Individuals could travel with relative ease, capital flowed across national borders, commerce flourished, and information was exchanged with minimal restrictions. These developments were encapsulated by the concept of globalization, a phenomenon extensively theorized by scholars such as Francis Fukuyama. In 1989, at the height of these transformations, Fukuyama published his seminal essay The End of History, positing that ideological conflicts would wane and that the world would move towards political and economic homogenization. This idea suggested that the “End of History” would coincide with the “End of Geography,” as globalization was expected to transcend national and cultural distinctions. In this envisioned world, adherence to rules would take precedence over the exercise of force, with the enforcement of these norms largely dependent on the actions of a benevolent superpower—the United States.

However, this ideological framework proved to be flawed. One of its consequences was the marginalization of traditional geopolitical approaches. This oversight contributed to several miscalculations and failures in Western interventions worldwide, particularly those led by the United States. To comprehend the complexities of contemporary global developments and to devise effective strategies, a balanced approach that integrates legal, economic, and geopolitical analyses is essential.

While globalization has yielded numerous benefits, including remarkable economic growth and a reduction of global inequalities, it has also generated significant challenges. New forms of inequality and exclusion have emerged, exacerbating socio-economic disparities. The multiple crises of the past decade can, in part, be attributed to the unintended consequences of unregulated global flows. In response, the world is now shifting in the opposite direction, transitioning from integration to fragmentation and diversification. Non-economic factors are playing an increasingly prominent role in shaping global dynamics. Religion, for instance, has re-emerged as a crucial force in both domestic and international politics.

This shift from an economic-centric discourse to one emphasizing geopolitics was not initially anticipated within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Along with a few colleagues, I sought to introduce geopolitical considerations into OECD discussions, often encountering resistance from an audience primarily composed of economists. However, ambassadors from countries that perceived themselves as directly threatened by post-imperial powers—such as Japan, Poland, and the Baltic states—were particularly receptive to these perspectives.

Despite the OECD’s predominant focus on non-geopolitical issues during my tenure as Ambassador, both the organization and its predecessor, the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), were originally conceived with a clear geopolitical rationale. Economic initiatives were not ends in themselves but rather means to achieve broader geopolitical objectives, including containing the Soviet Union and fostering positive relations with developing nations.

In the current global context, the OECD has the potential to play a pivotal role by re-engaging with its geopolitical foundations. This would not constitute a fundamental revision of its mission but rather a return to its original purpose, which had been overshadowed by the illusions of the past era. By embracing its geopolitical potential, the OECD can contribute more effectively to addressing the multifaceted challenges of today’s world.

The rise of China and other non-western powers is challenging the traditional dominance of the West; you argue that the world is entering an era of dichotomy between “the West and the rest” and you call for a ‘new Western doctrine’. What would this doctrine focus on? How would it work to ease the aforementioned division?

The relative economic weight of Western nations is diminishing, while many developing countries have experienced rapid economic growth. Consequently, the global economic balance of power is undergoing a significant transformation. Many non-Western countries increasingly assert their influence and express growing criticism and resentment towards Western powers.This critique is not without merit; historically, Western nations have often treated the rest of the world with exploitation, arrogance, and, at times, outright cruelty. However, while these grievances are justified, the resulting anger and resentment risk fostering division and could potentially lead to a breakdown of international cooperation.

A growing discourse surrounds the emergence of the so-called Global South, or even a broader Global South and East. This concept, rather than reflecting an empirical reality, appears to be constructed as a means of unifying opposition to Western dominance. Unlike the West, which has developed a degree of cohesion through institutions that facilitate cooperation, the Global South and East lack a comparable common framework. In fact, key nations such as China and India remain engaged in significant geopolitical conflicts. Given these internal divisions, it may be more accurate to refer to this grouping as the Rest rather than as a unified entity.

The increasing dichotomy between the West and the Rest presents significant risks for the World. Addressing this divide requires the development of a coherent ideological and political framework. A “new Western doctrine” should first and foremost adopt a balanced perspective on historical relations. It is essential to navigate between the extremes of traditional Western arrogance and the tendency to deconstruct Western history in a manner that disregards its significant contributions to human progress. In this regard, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) could provide an appropriate institutional setting for fostering such dialogue.

Given the multiple contemporary threats facing humanity—including existential risks—it is imperative to prioritize intellectual and political efforts aimed at fostering collaboration. Constructive engagement between the West and the Rest cannot be achieved without a well-conceived ideological and political foundation, supported by a conducive institutional framework. The persistence of aggressive, unilateral approaches to global challenges is unlikely to alleviate tensions. In contrast, a collective and cooperative strategy is more essential than ever in addressing the complexities of the modern international order -or disorder.

In your book “In the OECD: Geopolitical Theory and Diplomatic Action” you emphasize the growing importance of seas and oceans. Could you expand on that concept and outline its advantages?

The seas and oceans have played a fundamental role in human history. Naval battles have decisively influenced the rise and fall of empires. Through maritime routes, ideas have circulated globally, and religions have expanded their influence. The sea enabled the Greeks to extend their cultural model across the Mediterranean, laying the foundation for Western civilization. Spain, Portugal, England, France, and other European nations later replicated this Greek maritime and colonial expansion on a global scale due to their naval prowess.

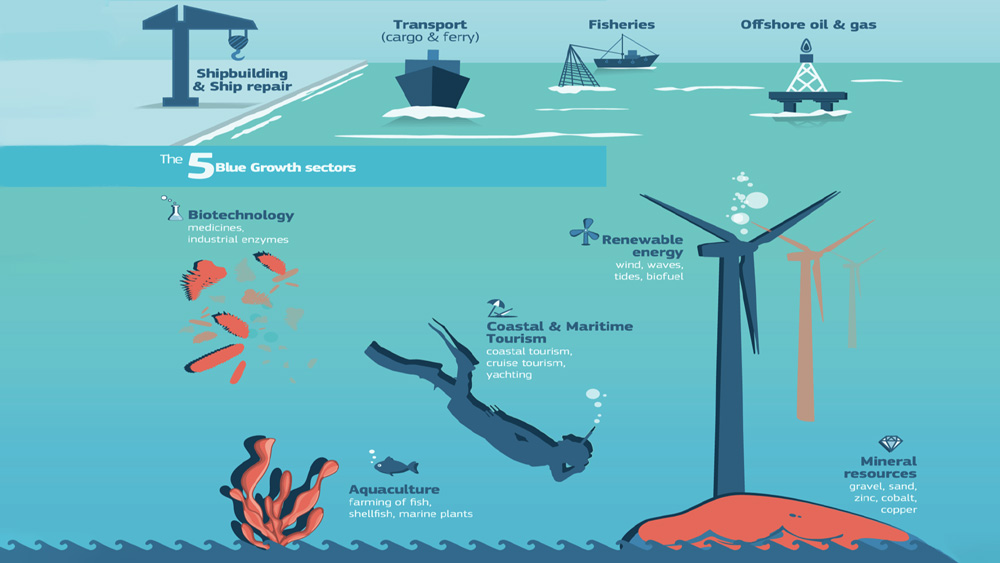

Today, the significance of the sea is greater than ever before. In addition to its historical role in navigation and trade, technological progress and economic growth present new maritime challenges. The increasing ability to extract resources from greater oceanic depths has transformed the sea into not only a medium for transportation but also a significant source of valuable materials. Consequently, maritime domains are acquiring characteristics traditionally associated with land, leading to territorial disputes over maritime areas. The concept of the “territorialization of the sea” encapsulates this evolving reality, which has profoundly impacted geopolitical relationships, such as those between Greece and Turkey in recent decades.

The maritime economy is expanding at a much faster rate than that of continental regions. Food production, mineral extraction, and energy generation have become prominent additions to traditional maritime industries, such as transportation. The expansion of global trade in the era of globalization has led to remarkable growth in the merchant marine sector. The Greek-owned fleet, in particular, has benefited significantly from the new opportunities presented by a more interconnected world. Simultaneously, the merchant marine has played a structural role in globalization. The advent of containerization and technological advancements in shipping have exponentially increased the capacity for transporting energy and goods, facilitating the rapid economic growth associated with globalization. While globalization has largely resulted from political decisions aimed at reducing trade barriers, the efficiency and fluidity of maritime transportation have been crucial in enabling its success.

Despite its economic benefits, rapid global growth has led to severe environmental challenges, with the maritime domain playing a central role in these developments. On the one hand, the world’s oceans face significant pollution, much of which originates from land-based sources. The increasing concentration of populations in coastal cities has exacerbated this environmental degradation. Beyond pollution, climate change also poses a serious threat to oceanic stability. Rising temperatures alter the physical conditions of marine ecosystems, triggering a cascade of climatic and environmental disruptions.

The growing strategic importance of maritime domains, combined with shifting geopolitical trends, has intensified global focus on naval power. The principle of freedom of the seas, once considered secure, is increasingly contested. Recent crises, such as Houthi attacks on more than 60 vessels in the Red Sea, the impact of the Ukrainian conflict on grain shipments through the Black Sea, and U.S. President Donald Trump’s remarks regarding the Panama Canal, underscore the fragility of global maritime security. These challenges have profound implications for the global economy.

The control of sea lanes and the strategic use of naval power—whether for offensive or defensive purposes—have long been fundamental to military strategy. However, in the emerging post-globalization era, naval capabilities are gaining even greater prominence. Heightened geopolitical tensions have led major powers, including the United States and China, to significantly expand their naval investments.

Finally, an essential yet often overlooked dimension of maritime significance is its role in digital infrastructure. A vast amount of global data transmission occurs via undersea cables that connect continents and nations. This digital interconnectivity further reinforces the strategic and economic importance of the maritime domain in the contemporary world.

In summary, the seas and oceans are central to global economic, environmental, and geopolitical dynamics. As new technological and strategic developments emerge, maritime domains will continue to shape the course of international relations and economic development in the twenty-first century.

Why do you advocate for Europe embracing the “archipelago” concept of interconnected entities linked by sea? How do you see Greece leveraging its maritime heritage and geographic position to lead in this paradigm shift?

With the exception of certain seafaring nations such as Britain, the geographical perspectives of most Europeans have been predominantly continental. The role of Germany in shaping geographical theory cannot be underestimated. Maybe under this influence, the European project, which emerged after the Second World War within the strategic and geopolitical framework of the transatlantic alliance, has gradually assumed a more continental character. Following the end of the Cold War, numerous Central European countries joined the European Union. Alongside the reunification of Germany and Brexit, these geopolitical transformations have significantly altered the European Union’s spatial configuration. Consequently, the Union’s center of gravity has increasingly shifted toward the east and the north, distancing itself from the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

This ongoing trend toward the continentalization of Europe may become even more pronounced if the war in Ukraine concludes with a relative victory for Russia and if the United States adopts a more isolationist foreign policy. Through both gradual and abrupt changes, the European project risks diverging from its foundational values.

Historically, Europe’s global influence in the 19th century and its role as a pioneer of civilization were largely shaped by its engagement with the seas and oceans. Europe’s openness, its spirit of adventure, and the curiosity of its populations were fundamental to the development of a distinctive culture—diverse yet unified by an outward-looking perspective.

Geography has played a crucial role in shaping this historical European trajectory, a process that can be traced back to Ancient Greece. Contrary to the modern perception of Greece as a land-based entity, the Ancient Greek world was a network of small regional entities interconnected by the sea. This spatial organization reflected the archipelagic nature of Greek civilization. The Ancient Greek Archipelago was not solely composed of islands but also included coastal plains separated by mountains and linked by maritime routes.

Europe has largely followed the Greek model. From a physical geographical perspective, it also possesses an archipelagic structure. The European continent, particularly to the east of the Elbe River, consists of peninsulas and regions connected to the seas and oceans via river networks, thereby embodying an amphibious character. Much like Greece, this archipelagic Europe has historically been politically fragmented. This division fostered a spirit of competition, exploration, and freedom. Conversely, the more continental values that characterize the eastern parts of Europe, including the vast Russian landmass, have traditionally been more conservative, hierarchical, and less inclined toward adventurous endeavors.

At the current European crossroads, the question of choosing between a continental or maritime orientation has resurfaced. The contemporary trend toward global fragmentation and increasing competition among major geopolitical blocs may suggest that a continental stance offers greater security. This dilemma echoes the ancient debate attributed to Themistocles: should the “wooden walls” serve as a fortification behind which protection is sought, or as ships that provide mobility and opportunity? Europe now faces a critical decision—whether to capitalize on the growing importance of maritime dynamics or to retreat behind its continental boundaries. Will it position itself as a continent or as an archipelago?

This debate holds particular significance for Greece. Given its maritime geography, historical engagement with seafaring, and robust merchant marine, Greece is naturally aligned with an archipelagic vision of Europe. From a strictly geopolitical perspective, however, Greece occupies a precarious position between its traditional maritime allies (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France) and the nations that may assume a dominant role in a continentalized Europe (Germany and Russia), with which Greece maintains strong ties through its membership in the European Union and religious links.

Nonetheless, Greece has the potential to play a pivotal role in shaping the future character of Europe. Its historical connections to the wider oceanic world, its longstanding tradition of dialogue with other Mediterranean civilizations, and its diasporic culture equip Greece with unique capabilities to contribute to Europe’s openness.

Additionally, the significance of the Greek merchant marine provides the country with a strategic advantage in both global and European affairs. However, to fully leverage its archipelagic strengths, Greece must work to mitigate the continental tendencies embedded within its state culture.

You consider population movements as the driving force of history. What are the main challenges demographic issues pose in this current conjecture? Considering the growing significance of diasporas, how can Greece better engage with its global diaspora to support its geopolitical and economic objectives?

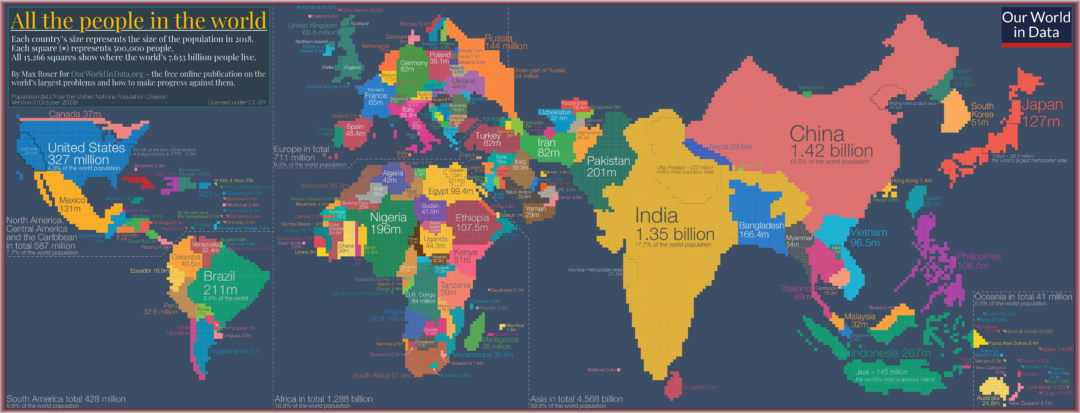

Population geography is arguably one of the most significant long-term factors influencing the evolution of humankind. Demographic developments, closely linked to physical geography, health conditions, migration patterns, and population densities, account for many of the forces shaping historical trends. These trends manifest in both short-term phenomena, such as the impact of invasions, and long-term transformations, exemplified by the rise of historical powers like ancient Egypt or contemporary China.

In the present era, one of the most pressing challenges is the unprecedented speed of demographic change, which rapidly alters established equilibria. A striking example is the demographic shift between Europe and Africa. In 1950, Europe’s population was more than twice that of Africa. Today, Africa’s population is approximately double that of Europe, and projections for 2100 suggest that Africa may have between five and six times as many inhabitants as Europe. Demographic trends are dynamic and often unpredictable, influenced not only by material conditions, which are relatively easier to forecast, but also by cultural factors, such as matrimonial behaviors, which shape population growth and structure.

The imbalances created by rapid demographic shifts generate migration pressures. Population movements are also driven by climatic factors and geopolitical tensions. Migrations are contributing to instability within host societies. This phenomenon is reflected in the growing support for right-wing political parties in various regions.

In the previous era, that of globalization, migrations played a significant role in fostering economic growth in host countries, despite political tensions. Diasporas have become increasingly important in the global economy, both as results and as agents of globalization. However, it remains uncertain to what extent this trend will be affected by political decisions influenced by rising xenophobic attitudes.

Given these dynamics, it is evident that population challenges are critical for the future. There is an urgent need for comprehensive research and analysis of population dynamics to formulate effective national and global policies. Such policies should aim to mitigate tensions, preserve the benefits of migration, and develop strategies to protect vulnerable populations.

Regarding the Greek diaspora, numerous efforts have been made to integrate it into the strategic initiatives of the Greek state. However, most of these efforts have not yielded significant results. Notably, little research has been conducted to analyze the reasons for these failures. Instead, similar strategies and rhetoric are repeatedly employed, often leading to predictable outcomes. The decision to live in the diaspora frequently stems from dissatisfaction with conditions in Greece. Consequently, unless these underlying conditions change, the diaspora’s potential contributions will remain constrained. In this context, the issue of meritocracy is particularly critical in shaping the relationship between the diaspora and Greek academic institutions.

Despite the challenges posed by state policies, the Greek diaspora continues to make substantial and positive contributions to Greece’s broader trajectory. It fosters openness within Greek society and enhances the perception of Greeks—and, at times, Greece itself—within host countries.

In your book, you showcase how a smaller nation like Greece can effectively leverage its position within multilateral organizations like the OECD, emphasizing the importance of bold initiatives, and the “strategy of the weak.” Could you expand on that strategy?

In a multilateral organization such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the principle of equality among member states is firmly established, irrespective of population size or economic strength. All Permanent Representatives possess an equal voice and the same capacity to take initiatives. However, while no external barriers hinder member states from proposing bold initiatives or influencing the strategic direction of the Organization, internal constraints often arise. Smaller member states, in particular, may experience a sense of inferiority that leads to self-censorship.

Paradoxically, smaller member states have a greater need to adopt bold strategies compared to their larger counterparts. Only through such an approach can they overcome their inherent disadvantages. The concept of a “strategy of the weak”— borrowed from guerrilla warfare—can be applied to diplomacy. In the absence of substantial political or economic weight to rival that of larger states, smaller nations must act in unexpected ways, leveraging surprise to counterbalance their limitations. These initiatives must be striking in order to attract attention and maximize their impact.

The objective of such initiatives is not only to secure strategic advantages but also to enhance the country’s image. A pertinent example is Greece’s bid for the position of OECD Secretary-General through the candidacy of Anna Diamantopoulou. Although Greece was ultimately unsuccessful, despite Diamantopoulou’s strong performance, this effort was not in vain. The campaign significantly altered perceptions of Greece within and beyond the OECD at a time when the country’s international reputation was at a low point. Greece transitioned from being seen as a passive recipient of foreign support and advice to a nation actively seeking leadership roles within the Organization. This ambitious campaign laid the groundwork for two subsequent successful initiatives that further enhanced Greece’s image: Kyriakos Pierrakakis’s election as President of the Global Strategy Group and the OECD Council’s approval of Greece’s proposal to establish the OECD Crete Population Center.

In the contemporary global landscape, a country’s image plays a crucial role in shaping economic, political, and geopolitical decisions. In the economic domain, investment decisions are particularly susceptible to perceptions and reputational considerations. Similarly, political and geopolitical choices are often influenced by subjective evaluations. By navigating an international organization with creativity and strategic acumen, a country can actively shape its global image. However, the strategic imperatives of smaller and larger countries differ fundamentally. While larger states tend to adopt more conservative approaches to safeguard their established positions, smaller states must assume greater risks to distinguish themselves and emerge from the constraints of relative obscurity.

One your biggest achievements as Greece’s Ambassador to the OECD was the establishment of the OECD Center for Populations in Crete. How does the Center aim to address global challenges related to population dynamics, and what contributions will it bring to the OECD’s existing work? What benefits does Greece, and the island of Crete, anticipate from hosting this center?

As previously discussed, population dynamics represent one of the most significant—if not the most critical—challenges facing contemporary societies and the global community both today and in the future. However, there is currently no institutional framework capable of examining and conceptualizing this issue in a holistic manner. Various aspects of population studies are addressed in separate disciplinary contexts. For instance, demography is studied independently from migration, while the economic consequences of population decline on the workforce are analyzed in a different academic field than the political implications of migration. There is a lack of a comprehensive perspective on the spatial distribution of populations, their dynamics, and migratory flows. Furthermore, cultural aspects are not sufficiently integrated with economic conditions, particularly in cases where demographic expansion occurs without corresponding economic growth. Finally, no systematic provisions exist to address emergencies affecting populations under stress or persecution.

Given the vast scope of this field, the need for a centralized hub to integrate the study of various facets of population challenges is increasingly urgent. This necessity led to the proposal of establishing such an institution in Greece. Any new institution requires a strong symbolic foundation, and Crete was identified as an ideal reference point for a global population center. Positioned between Europe, which faces a declining population, and Africa, which is experiencing rapid population growth, Crete symbolizes the essential connection between different demographic trends worldwide. Historically, Crete has served as a cultural crossroads, having been inhabited or influenced by Minoans, Mycenaeans, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Venetians, Ottomans, Jews, and others, making it a powerful emblem of coexistence. Additionally, Crete occupies a significant place in human history and is recognized as a cradle of maritime navigation.

The OECD Crete Population Center, while situated in Greece, is not a Greek institution. This arrangement aligns with OECD principles, which dictate that its centers operate under OECD management and leverage its intellectual and political resources without becoming « nationalised ». Greece’s role is to serve as the host nation, facilitating the center’s operations. For the Crete Population Center to attain global significance, it must fully engage OECD resources, ensuring that it fulfills its intended role on an international scale.

Greece and Crete stand to benefit from the OECD Crete Population Center only if it evolves into a genuinely international hub. The annual conference that the center is mandated to organize must develop into a major global event in order to attract significant international attention to Greece and Crete. Achieving this objective, however, requires substantial resource mobilization by the OECD, which, at present, appears to be insufficient. Consequently, the OECD Crete Population Center currently relies on Greece’s limited financial, intellectual and human resources. By tolerating thus the « nationalisation » of its Crete Population Center, the Secretariat of the OECD has undermined the decision of its Council to create it.

President Trump’s recent statements regarding Gaza have forcefully revived the debate on population transfers, a historically significant issue that gained prominence following major global conflicts. Notable examples include the Greek-Turkish population exchange after the First World War, the large-scale transfers of German populations following the Second World War, and the displacement associated with the partition of India.

In this context, a well-established and influential OECD Crete Population Center would have served as an appropriate forum for such discussions. Had it been developed as originally envisioned, Crete might today be a focal point of international diplomatic attention.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Rethinking Greece

- Rethinking Greece | Peter Frankopan: “We are living in an age of imperial revivals”

- Rethinking Greece | Davide Rodogno: Multilateralism plus prevention is key for a better future in humanitarian interventions

- Rethinking Greece: Georges Prevelakis on Contemporary Hellenism as a “cultural sediment” linking Europe with the emerging multipolar world

TAGS: GEOPOLITICS | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | OCEANS & SEAS | SHIPPING