Konstantina E. Botsiou is Professor of History and international Relations at the Department of International and European Relations of the University of Piraeus. She was previously Associate Professor at the University of the Peloponnese (Corinth), where she also served as Vice Rector. Since 2016 she is Visiting Professor at the Hellenic National Defense College (HNDC) and serves on the board of Directors of the Council for International Relations-Greece. From 2001 until 2018 she was Director of Publications, General Director and Vice President of the Konstantinos Karamanlis Institute for Democracy.

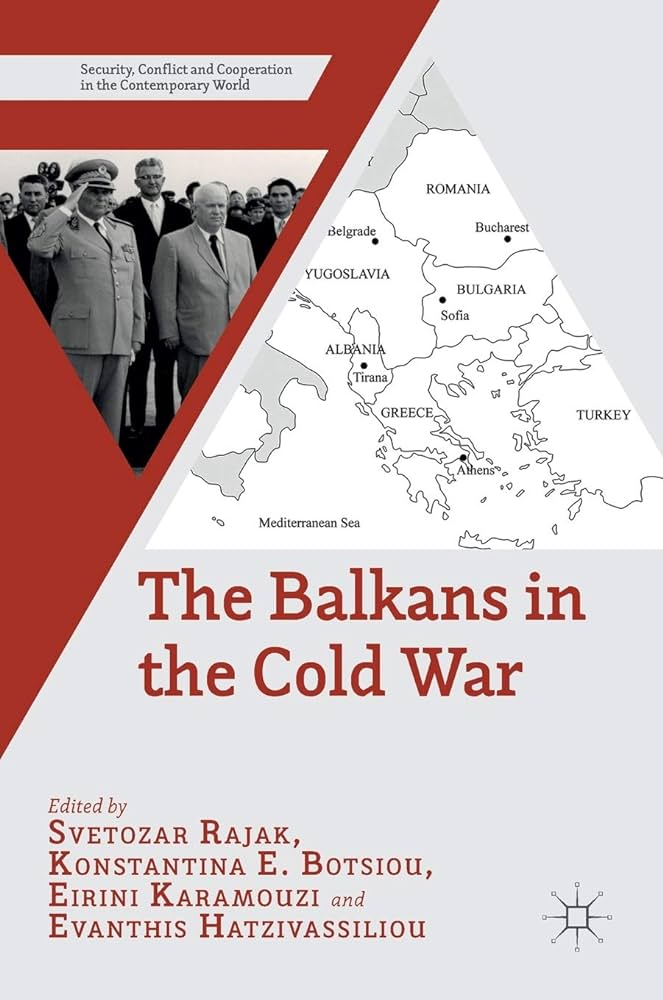

Her publications focus on modern and contemporary history, European integration, the Cold War, Balkan history, Euro-Atlantic relations, political parties, defense and foreign policy. She has authored, co-authored and edited over 15 books and 150 academic articles, among them the books 1821. From the Revolution to the State (in Greek, 2021), The Balkans in the Cold War (2017) and The founders of the European Integration (2012).

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne,* Professor Botsiou spoke to Rethinking Greece** on what elements made the Treaty such a solid foundation for Greek-Turkish reconciliation; on the anti-revisionist policy adopted by both counties at the time; the “cruel novelty” of the mandatory population exchange between Greece and Turkey; the Treaty’s contribution to the wider region’s geopolitical balance; and finally on why, as a multilateral peace treaty, the Treaty of Lausanne cannot be amended.

The Lausanne Treaty provided the foundation for a peaceful co-existence between Greece and Turkey during many decades. What do you believe were the elements of the Treaty that made this possible?

A combination of factors made possible the peaceful coexistence, mainly anti-revisionism after defeat of both Greece and Turkey. This made entanglement in a new war unattractive since neither country believed that the gains would exceed the losses. The nature of the dual Treaty of Lausanne as a) a Peace Treaty of the Allies with the Ottoman Empire for the First World War and b) as a replacement for the ill-fated Treaty of Sevres provided a solid fundament for Greek-Turkish conciliation on the basis of mutual defeat. The paramount aim of the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July 1923) regarding Greece and Turkey was to exclude future bilateral wars that could by definition endanger the international balance of power. This aim was mostly served by a) the compulsory exchange of populations and b) the clauses regarding demilitarization. These clauses enhanced bilateral rapprochement since neither country would be able to attack each other. At the same time, both countries would act as a joint bulwark against pressures from the North, thus serving the strategy of the Allies who considered Bolshevik Russia -later the Axis- the major threat of the interwar years. By uniting the eternal Russian danger with the communist threat, the new Bolshevik regime posed a geopolitical and ideological danger to the balance of powers in Europe despite Stalin’s preference for inward-looking reconstruction. Britain’s instrumental role in Greek-Turkish arrangements at Lausanne reflected London’s suspicion towards its diehard rival in Eastern Europe. That global element convinced the two countries that they could share the geography that was created by war in order to play a stabilizing international role and use their geopolitical position for building up their war-ridden societies.

In your announcement at the ELIAMEP Conference for the 100 years of the Lausanne Treaty, you mentioned that it was (and still is) a modern Treaty. Could you expand on that?

The Treaty of Lausanne has demonstrated remarkable durability. A key aspect of its longevity was the fact that it simultaneously ended the First World War with the Ottoman Empire that was about to become modern Kemalist Turkey (it was founded three months after the Treaty, namely on 29 October 1923), on the one hand, and turned the page in its relations with the Allies, including Greece, on the other. Both countries adopted an anti-revisionist policy which was sustained in the Second World War and in the Cold War. In the Second World War half of the 8 countries that signed the Treaty of Lausanne followed a revisionist policy and cooperated with the Axis, but not Greece and Turkey. Greece remains on the same line to this day, whereas Turkey adopts revisionist claims. Nevertheless, the Western orientation of the two countries unites their broader interests as they were tied together at the Treaty of Lausanne, originally with Britain as the closest ally, later the USA.

In the same announcement, you characterized the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, as a “cruel novelty”. How would you evaluate, 100 years on, the impact of this population exchange on both countries?

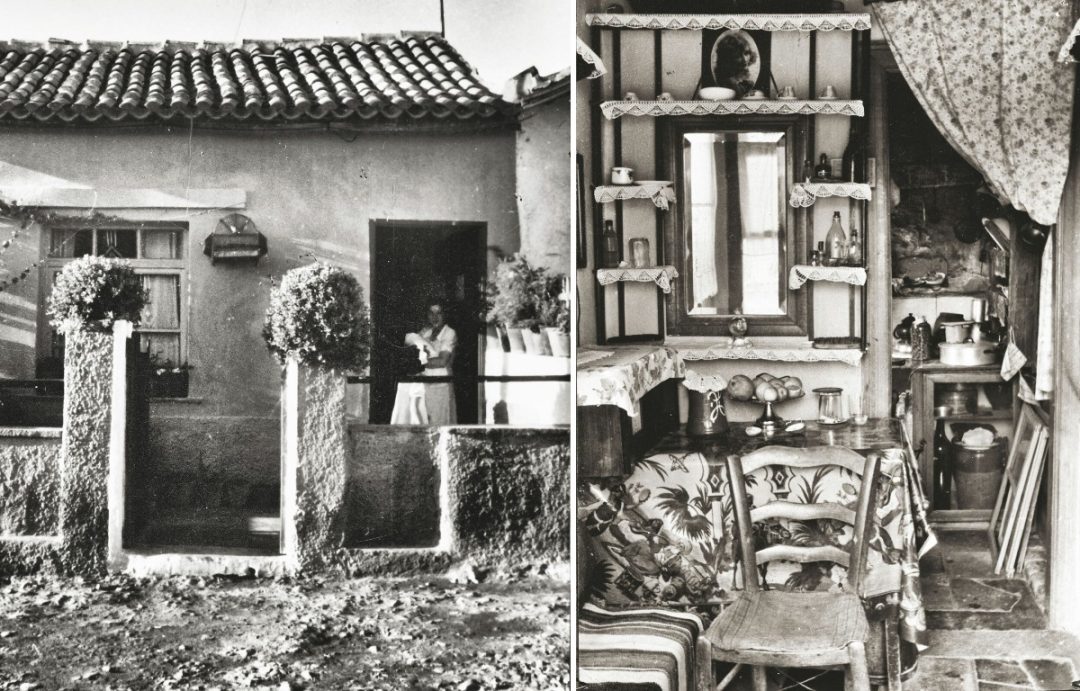

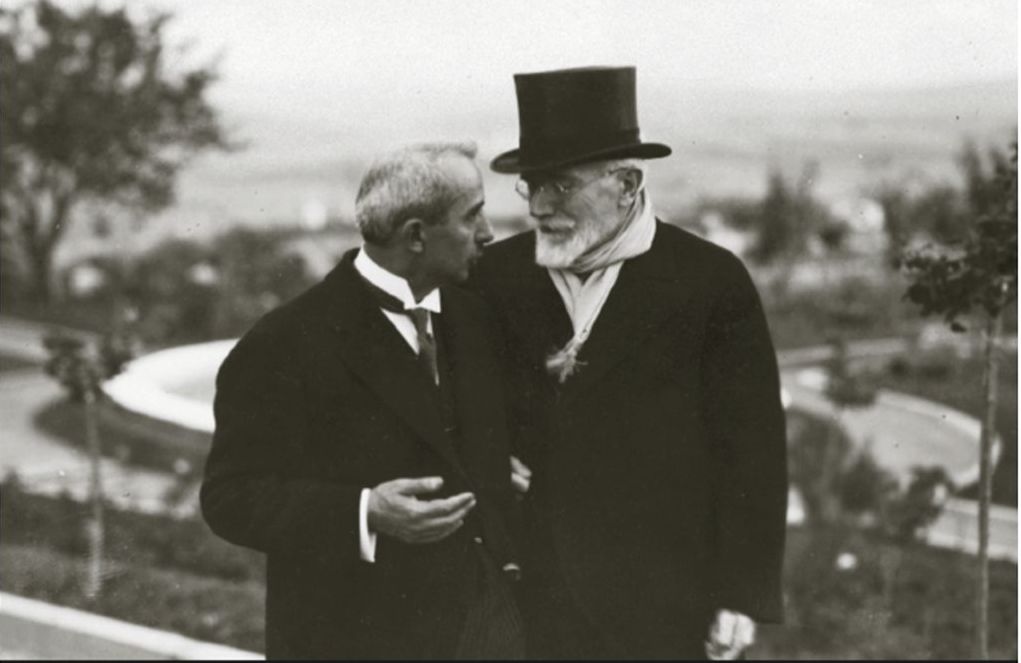

The Lausanne Treaty initiated a century of peace or “no-war” – as it was once described in the 1980s- between Greece and Turkey despite their dispute and the Turkish invasion in Cyprus in 1974. Thus, the Treaty was a turning point from the past considering the continuous Greek-Turkish wars in the previous century. The exchange of populations was considered a prerequisite for this, in order to deprive both countries from extensive rights over large minorities and terminate territorial claims that were based on their existence. The exchange was actually compulsory, quite a departure from the voluntary exchanges that were not infrequent at that time; one had already taken place between Greece and Bulgaria after the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (1919). Eleftherios Venizelos himself had contemplated an exchange of populations also with Turkey in 1914 to stop Turkish persecutions in Macedonia and Thrace. It came almost 10 years later, but this time in a compulsory form. That qualitative difference that sought to eradicate any roots of grievances was indeed a prerequisite for the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne. The relevant agreement was signed 6 months earlier, on the 30th of January 1923. The exchange of populations was brutal for the people and the countries involved, especially Greece that had to deal with both defeat and urgent social conditions. Hence, the exchange was a “cruel novelty”. It entailed deep human suffering; at the same time, it created conditions of national homogeneity when nationalism was at its peak and enabled Greek-Turkish rapprochement, even Greek-Turkish alliance in the coming years. The re-settlement of refugees was quite an accomplishment, owed greatly to the intensive efforts of the American-led Refugee Settlement Commission (RSC) which completed it within a few years (1924-30). However, it took the refugees generations to become incorporated and accepted in Greece’s society, whereas several refugees longed for substantial reparations for the properties they had left behind or even believed in repatriation. In 1930 those expectations proved futile as the governments of the two countries signed several treaties including a Treaty of Friendship in Ankara and decided to a mutually quit refugee compensations. Geopolitically that transformed reconciliation into friendship. Politically it cost dearly, foremost to Venizelos, who lost thousands of refugee votes in the 1932 general elections. But Greece and Turkey stressed national homogeneity as a source of power and sovereignty against external pressures.

The Lausanne Treaty was a multi-lateral treaty, with eight signatories. What would you say was the Treaty’s contribution, not just to Greece-Turkey relations, but to the geopolitical balance in the wider region?

The death of the “sick man of Europe” as the Ottoman Empire had been characterized in the previous century resulted in a new balance of powers among smaller nation states in the Balkans which started anew on an equal basis with their century-old opponent. The national life of those states also began when communism was a rising ideological force in Europe. For that reason, Greece and Turkey were integrated into the broader strategy of the Western Great Powers against Bolshevik Russia. In a way, the Western orientation of Greece and Turkey started with the Treaty of Lausanne. The Treaty also granted territorial stability in the Middle Eastern territories that were regulated by the colonial powers at Lausanne. When they became independent countries they aspired to specific borders that were set then in order to avert destabilizing external influences, Turkish or Russian.

Today’s regional wars upset that stability as the Arab spring and the War in Syria have shown. The most important change, though, is Turkey’s effort to emerge as regional hegemon which reminds of the unwelcome Ottoman past to all countries of the region. This is also a main source of Greek-Turkish tensions which take place against a difficult geography as both countries are members of NATO and share access to the chokepoints of the Mediterranean (Straits, Suez Canal). Still, Turkey does not seem determined to change the status quo created by the treaty as it would risk destabilizing the entire region and this would undermine the interests of its powerful allies like US and NATO. The collision of Turkey with Israel is a sign of Ankara’s difficulty to play the Muslim card and at the same time remain a Western country.

What is the legacy of the Lausanne Treaty now? What would you answer to claims that the treaty “expires” and has to be revised?

As is well known, the Treaty of Lausanne is a multilateral peace treaty and not a bilateral Greek-Turkish Treaty. Peace Treaties are not amended even before the Vienna International Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) was enacted, because they define borders and territorial regimes. Turkey’s efforts to revise the part of the Treaty that concerns Greek-Turkish relations cannot be acceptable since the Treaty is a coherent legal entity including 28 acts. Only one part regulates Greek-Turkish relations after the Asia Minor War. On the other hand, the Treaty facilitated Greek-Turkish rapprochement, for instance through demilitarization, but did not link demilitarization with sovereignty as Turkey claims today. Thus, Ankara neglects the bilateral revision of the relevant clauses, de jure with the Montreux Treaty (1936) on the eve of the Second World War, de facto in the Cold War after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Last but not least, to state only a few examples, Turkey also questions Greek sovereignty over Dodecanese islands although it resigned from all rights and privileges on them since they were ceded to Italy under the Treaty of Lausanne. Ankara’s attitude today shows a propensity to revise the entire status in the Aegean Sea as part of a hegemonic Turkish strategy towards neighboring Greece. Greece is regarded as a geopolitical obstacle to fulfil that strategy and the Treaty of Lausanne is regarded as a legal obstacle to this political endeavor that blurs crucial chapters of modern world history.

** The Treaty of Lausanne, the most enduring of the post-World War I peace accords, is a historic treaty signed on July 24, 1923, establishing national borders in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, with the aim of restoring peace in the region after the disastrous First World War. The treaty was signed by the Republic of Turkey, which had succeeded the defeated Ottoman Empire, on the one hand, and by the Allied and Associated Powers (France, United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, Greece, Serbia and Romania), on the other hand. One of the most radical elements of the Treaty of Lausanne, particularly from a humanitarian point of view, is the obligatory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey.

** Interview to Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Greek News Agenda

- Rethinking Greece | Evanthis Hatzivassiliou on the Treaty of Lausanne and its enduring legacy

- Conference | 100 Years since the Treaty of Lausanne: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

- Rethinking Greece | Davide Rodogno: Multilateralism plus prevention is a way of imagining a better future in humanitarian interventions

- Rethinking Greece | Emilia Salvanou on the Greek-Turkish population exchange after 1922 and the making of Greek refugees’ memory

TAGS: FOREIGN AFFAIRS | GEOPOLITICS | GREECE-TURKEY RELATIONS | MODERN GREEK HISTORY