Κοstis Kornetis is Assistant Professor of Contemporary History at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. He has studied History and Political Science in Munich, London and Florence, taught history at Brown University, New York University and the University of Sheffield. His monograph “Children of the Dictatorship: Student Resistance, Cultural Politics and the ‘Long 1960s’ in Greece” (2013) won the Edmund Keeley prize, while he has co-edited the volumes “Consumption and Gender in Southern Europe since the “Long 1960s” (2016), “Rethinking Democratisation in Spain, Greece and Portugal” (2019), and “The 1969 Greek Case at the Council of Europe. A Game Changer for Human Rights” (2024).

Kornetis’ research is focused on the history of dictatorships in southern Europe and the social movements of the twentieth century, especially around 1968 and the ‘long 60s’. Likewise, he has published theoretical reflections on transnational history, oral history and the relationship between history and cinema. His most recent line of research focuses on the so-called history of the present and analyzes the history of democratic transitions in Spain, Portugal and Greece and the collective memory built around them.

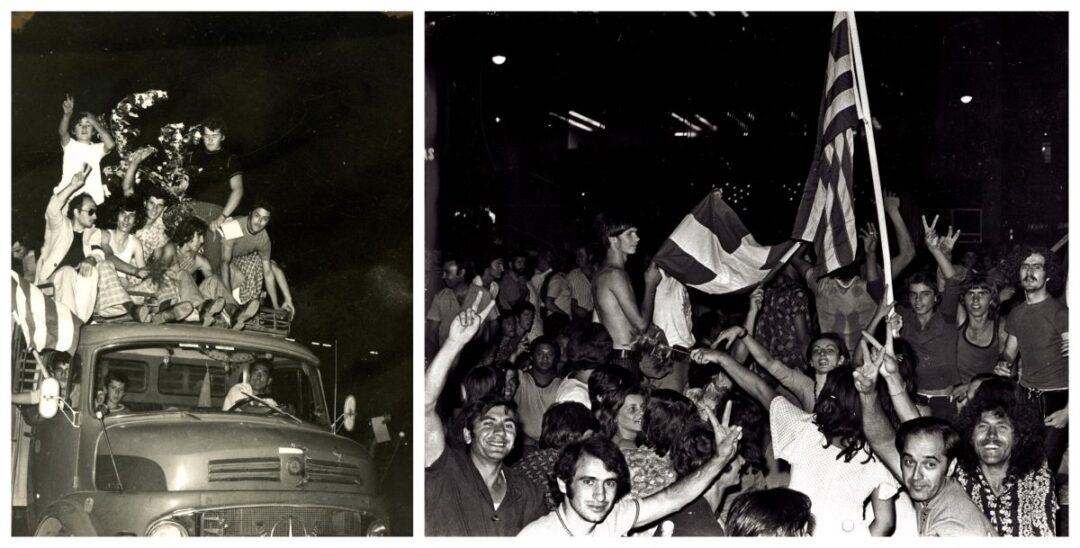

On the occasion of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the restoration of Democracy in Greece as well as the impending publishing of his new monograph “A Collective Biography of Southern European Democratization,” professor Kornetis spoke to Rethinking Greece* on how Greece, Spain and Portugal experienced and remember their respective democratic transitions, the imprint of the Metapolitefsi (post-dictatorship) period in Greek culture and of course, its political legacy.

Your latest book manuscript is titled “A Collective Biography of Southern European Democratization: The Age of Transitions.” Could you tell us a bit about this periodization of three generations and its significance?

The Age of Transitions is about how Greece, Spain and Portugal remember, represent, and commemorate their transitions today beyond similarities and differences: how moments of change, and the steady acceleration of events, are reflected in memory; how the transitions solidified into settled ‘autobiographies’ of individuals, of a generation, of each nation. I expound these transitions and their afterlives according to multiple political generations, identifying missing links between stories, storytellers, contexts, and respective political generations.

Hence the book shifts the attention of inquiry from institutional breakthroughs and setbacks to political generations. As transitions are inherently ‘multi-generational’ the book looks at three distinct generations. One that went through the events of the transitions as young adults and hence remembers them fully. One with people who were children during the transitions – not old enough to have participated in the events, but old enough to hold memories of them, however vague. And a third one, which was not born then, but contains ‘projective’ (post)memories of the events that go beyond family memories and recollections. The book is largely based on people who have become academics, artists and activists, at times with an overlap between these different functions, and hence combines their own lived experience with their capacity to reflect on the events using the tools of their disciplines or craft. Several of them have worked on the very issue of transitions, hence the book operates on multiple levels of analysis.

In the book I sought to explore the intersection between personal recollections and collective remembrance, linking democratization studies to oral history and memory studies. I look at the memory battles, or conversely the synergies, between two sets of opposing poles: between individual memory and collective memory, and between private microhistories and dominant transition narratives. To do so, I bring into dialogue historical and biographical time. The similarities in memories across time, geography, and generations are surprising, outweighing their differences.

Generational memory, I conclude, plays a crucial role in shaping the political, social and cultural developments of the entire post-authoritarian period, affecting people’s political conclusions. The diverse memories are, the book argues, concomitant with the myriad experiences of transition; and these unique experiences, and their memories subsequently structure present political space. They determine the meaning of democracy, as well as the identities of the political Left and Right.

What do you believe were some of the biggest challenges Greece faced in transitioning to a democratic system? How did the initial years of Metapolitefsi shape the political landscape of Greece?

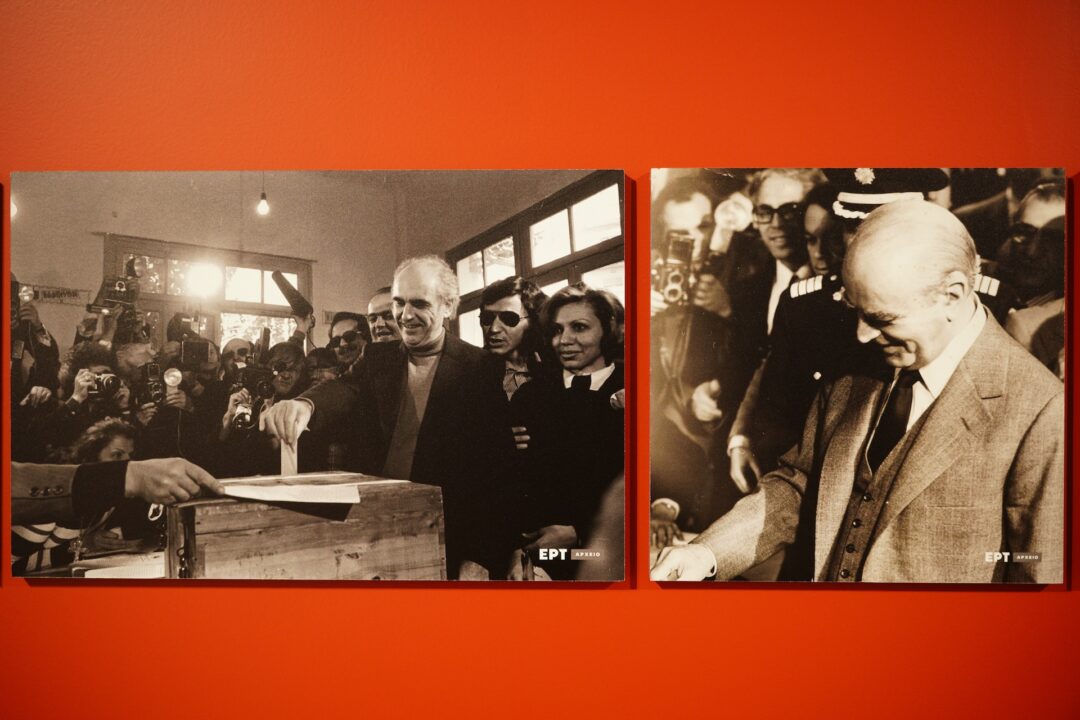

Greece transitioned to a full-fledged democracy after many decades of political stalemate, extreme polarization, political exclusion and violence. Its post-1974 democratization did not signify the return to the status quo ante, meaning the pre-1967 state of affairs, but rather the end of the long post-civil war period. It was the final end of the “30-year war” according to novelist Alexandros Kotzias’s acute description, himself being an emblematic literary figure of the transitional years. So Greece had to move away from the anticommunist state of ethnikofrosyni and the ‘sickly democracy’ [καχεκτική δημοκρατία] per Ilias Nikolakopoulos, into a plural, parliamentary system, that included the banned Communists after decades of persecutions. In this respect, and despite inertias, it proved to be successful – with the last chapter of the revival of the repressed being written in 1981 with PASOK’s spectacular victory. The three additional challenges being the settlement of the nature of the country’s political system, the constitutional process, and the issue of transitional justice were all swiftly and efficiently dealt with: Greece abolished monarchy once and for all, voted a liberal Constitution, and put the culprits of the 1967 coup d’état on trial and in prison. Another great success was that for the first time in the 20th century the army stayed in the barracks where it belongs. Less successful was the issue of ‘dejuntification’, or cleansing, of the police and the judicial system from authoritarian residues.

How does Greece’s experience of transitioning to democracy compare with Portugal and Spain?

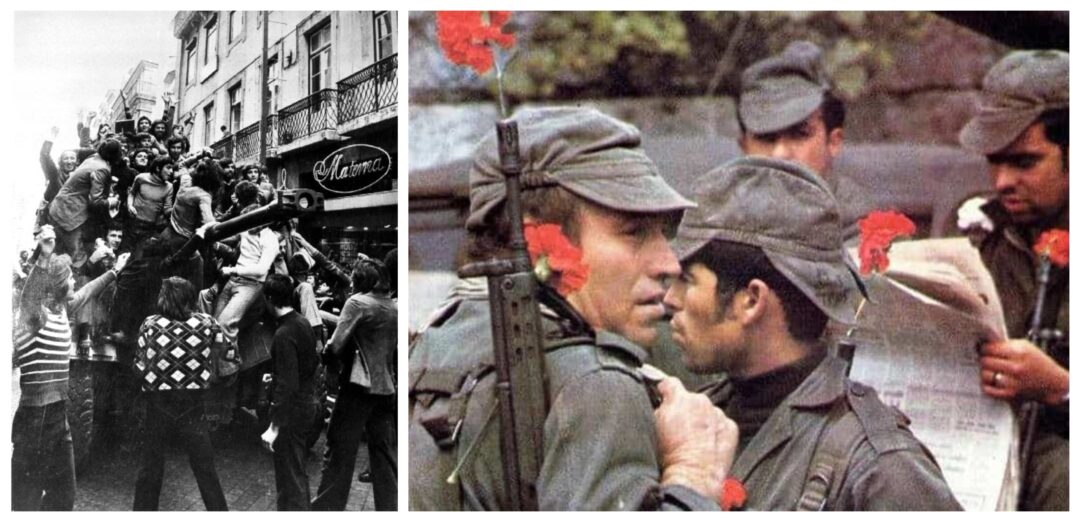

These are three societies that had to deal with a different set of problems and different chronologies as far as the onset of authoritarianism is concerned, with the Iberian dictatorship being residues from the interwar years. Nevertheless, they synchronized at the time of their transitions, being faced with similar challenges as far as democratic consolidation was concerned. Portugal faced the crucial issue of the loss of its empire, propelled by a revolutionary process, hence a full rupture with the authoritarian past. Spain, on the other hand, experienced a ‘pacted’ transition, based on an agreement between regime holders and recently legalized political parties aspiring to power. This transition from within had its own complexities but was hailed for a long time as a ‘model’ transition. The greatest challenge of the new democracy were the local nationalisms – Basque and Catalan, above all, a legacy that the transition bequeathed to the present day. Greece of course had its own major issue which was the ongoing conflict in Cyprus that followed the Turkish invasion. It did not deal with this issue head on as it was of existential proportions – a possible direct involvement in warfare might have had tremendous consequences for the country as a whole. Instead Karamanalis opted for the clever move of the removal from NATO’s military wing to let off steam. However, this lack of direct engagement of sorts fuelled resentment and a lingering trauma – especially in Cyprus proper, of course.

The Age of Transitions is actually grounded in the premise that each country’s transitional process led to distinct political histories and national trajectories. These distinctions, in turn, caused major variation in how each generation remembers the transitions. How people remember the transitions and both their achievements and their setbacks matters because these people became the very subjects of democratic rule.

All three Transitions (Portuguese, Spanish, Greek) are considered as “political masterpieces”. How has this perception changed over time? Do you believe the public memory of the Transitions still plays a role in contemporary politics?

This perception has changed a great deal, especially regarding the Spanish case, which spearheaded the idea of the “model transition” which inspired the entire field of ‘transitology’ back in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s. It was supposed to be smooth and peaceful but nowadays we are much more aware of the bloody aspects of that transition, with extreme right-wing and left-wing political violence ruling the day, but also institutional one lurking from the Francoist era. More importantly, Spain’s transition was based on a so-called pact of silence regarding the past and the flagrant lack of transitional justice as far as Francoist crimes are concerned. This particular issue has come to be a matter of intense debate in the past years. Portugal on its own right was considered a rare case of a revolution that was both bloodless and without an authoritarian outcome. By contrast it led to a long and stable democracy ever since 1976 and the first free elections. However, some dark aspects concerning in particular the issue of war crimes, were never tackled head-on, as the militaries who made the revolution were themselves involved in that bloody conflict that lasted thirteen years. Connected to the above was the issue of half a million refugees from the ex-colonies, dubbed the ‘returnees’ who experienced great difficulties in becoming assimilated in Portuguese society. These are all issues which were slipped under the transitional carpet. For Greece dejuntification and Cyprus remained, as mentioned above, unresolved issues.

Such issues experienced a powerful comeback in the past years due especially to a new generation of thinkers, intellectuals, politicians, activists and artists wanting to promote uneasy memories. Definitely in terms of academia there is a much more analytical and critical approach to the transitions, backed up by more reflexive writings and artwork. In all three cases the public memory of transitions became weaponized during the years of the Great Recession (2009-2015). While the hegemonic discourse transitioned from celebratory to condemnatory, we might be reaching a point of more balanced approaches. After all, fifty years since the events are always a landmark point that triggers more reflection.

What was the imprint of the Metapolitefsi period in Greek culture and arts?

If we consider as Metapolitefsi the short period of 1974-75 or even 1974-81, its imprint was great, since this was a time of great effervescence. It is a time that is very much connected to the last years of the Colonels’ regime. In music, cinema, and the visual arts, we witness the dynamism and passion of the dictatorship years being channeled into creative expression. Contestatory action was fueling the arts and vice versa. So, we need to keep in mind the fact that, even though 1974 is a rupture and a turning point politically, much of what is happening in the arts has its origins, inspiration and raison d’etre in the previous era. Both New Greek Cinema and the dawn of the Greek political song date in the dictatorship years – and the same applies to the so-called Generation of the 70s in literature, or even the burgeoning counterculture and figures such as Leonidas Christakis, for instance. The current exhibition at the National Gallery of Greece on “Democracy” charts precisely this dynamism and the suffering of the Junta years being transformed into creativity in the mid-1970s onwards. As the exhibition shows, similar traits can be spotted in the Iberian Peninsula around the time of the fall of the dictatorships as well.

What I find interesting in the book is the revival of certain political and aesthetic norms during the Great Recession (2009-2015) in Greece. The political or éngagé art had a comeback, or an afterlife – in a way several artists felt the need to go back to codes of a time of rupture and renewal to deal with a time of stagnation and crisis.

What do you think is the legacy of the transition in Greece?

The legacy of the transition is twofold. The present stable parliamentary system that managed to overcome grave crises has its roots in those very days, including the Constitution, which has remained basically unaltered. The ‘big bang’ of the Metapolitefsi, in historian Antonis Liakos’ fitting term, generated the socio-political plurality that characterized Greece in the following decades. I don’t share the negative appraisals of the Metapolitefsi which dominated the 2010s, identifying it with corruption, cronyism, clientelism and populism, to name but a few examples. Even though such traits existed and continue to exist, I doubt that they are the main characteristics of Greek democratic practice – to quote Robert M. Fishman’s term– from 1974 to the present.

The second one has to do with the dual nature of the Greek transition: it bore from the very outset both the legacy of the Polytechnic uprising in November 1974, which discredited Papadopoulos’ ‘liberalization’ ‘from below’, and the actual collapse of Ioannidis’ junta on 23-24 July1974, that triggered regime change ‘from above’. The abundance of social movements during the first Metapolitefsi years and the continuous symbolic significance of the Polytechnic till the present-day attest to that dual significance. What is more, much of what happened in the first Metapolitefsi years and in a way shaped Greek democratic practice was moulded through these characteristics. In my book I quote legendary left-wing composer Mikis Theodorakis boasting in 1975 about Karamanlis’ above-mentioned withdrawal of the country from NATO’s armed wing, as being a left-wing demand all along. It is this dialogue between Left and Right, the government and the movements, unheard of until that moment, that can and should be catalogued alongside the Metapolitefsi characteristics – and why not, a legacy that should be rescued.

*Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

Read also from Greek News Agenda:

TAGS: DEMOCRACY | METAPOLITEFSI | MODERN GREEK HISTORY | SOUTHEREN EUROPE