Kristina Gedgaudaitė is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow at the University of Amsterdam. She has published a monograph based on her thesis titled “The Memory of Asia Minor in Contemporary Greek Culture” by Palgrave Macmillan Memory Studies Series (2021). Previously, she was a Mary Seeger O’Boyle postdoctoral research fellow at the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton University. Her research interests fall within the fields of 20th century Greek literature and culture, cultural memory, migration, comics and graphic novels.

Kristina Gedgaudaitė spoke to Rethinking Greece* on how representations of the Asia Minor refugee experience in popular Greek culture have changed through the decades, on her work on Soloup’s graphic novel Aivali, on why the graphic novel is an apt format to represent a difficult historical past and finally on the educational project Greek Studies Now.

Your most recent research project focused on the memory of the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) in contemporary Greek culture. How have representations of Asia Minor refugee experience changed in popular culture through the decades? Was there a turning point when refugee memory found its place in Greek history?

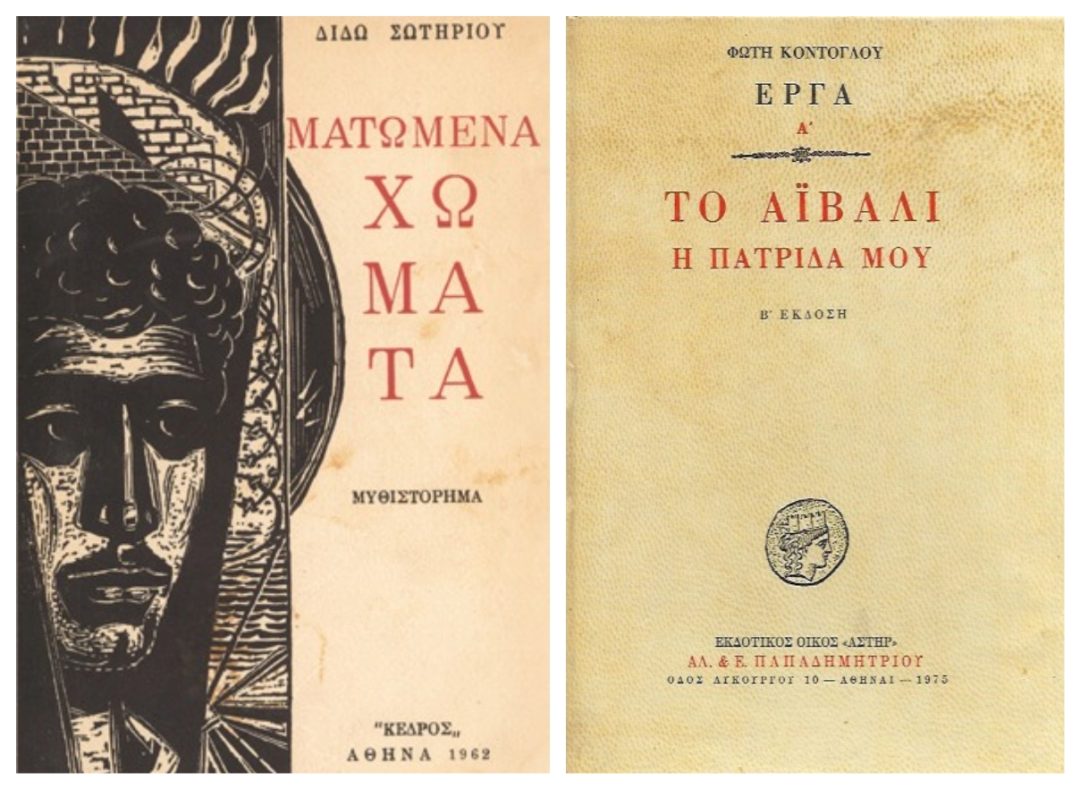

The memory of the Greco-Turkish War always played an important role in Greek culture, yet this role has not been the same over the period of the last hundred years, as it changes shape in accordance with the needs of the communities by which it has been invoked. To illustrate this point, my book Memories of Asia Minor begins from the testimony of a refugee woman, Marianthe Karamousa, recorded by the Center for Asia Minor Studies; at a certain point of accounting her hardships, she laments that these experiences do not find a place in history. The testimony is recorded in 1962, that is forty years after the war, the same year when many commemoration ceremonies were held across Greece. It is also the year that some of the works that are today regarded as most prominent on this subject were published, such as Aivali, My Homeland by Fotis Kontoglou or Bloodied Earth (transl. Farewell Anatolia) by Dido Soteriou. Yet this refugee still felt that her experiences lay outside history, even at the moment of narrating those experiences for the historical record to the interviewer of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies. The testimony was published in the first volume of the Center for Asia Minor Studies’ collection The Exodus in 1980; the decade of the 1980s can indeed be regarded as the moment when refugee experiences assume great significance in the public sphere. All this happens at a transnational conjuncture, when a human rights discourse is on the rise and there is increased attention to individual stories that lay claim to these rights. Yet, while certain experiences, such as the exodus from Smyrna become watershed moments in the history of the Greco-Turkish War, others, such as those of Turkish-speaking Christians that left Greece, never obtain the same visibility. In this context, the focus of my project is on the role memories of Asia Minor come to play in present-day Greece.

What is the role of memories of Asia Minor in contemporary Greek culture? How do they connect to Greek society’s current hopes and fears?

I view cultural memory as a toolbox, which can indeed provide tools to position oneself in history and to address the present in a certain way, be it to assume a distinct cultural identity, to provide a template for responding to present-day issues, or to advocate for recognition and social justice. The two examples of this process I focused on in my research are the history textbook edited by the team led by Maria Repousi and the 2015-2016 response to the currently ongoing refugee crisis. Both attracted wide public attention, albeit in different ways: the former leading to outcries of outrage, while the latter – to solidarity. Perhaps one could say that the underlying premise of my work was that we need to take such emotions seriously, to understand where they come from and where they lead.

It was also important for me to foreground that while memories operate within certain social, cultural and political frameworks, the meaning that they take on is ultimately determined in an encounter with others. During my research, I witnessed a number of occasions when cultural works dealing with refugee memories deemed alternative visions were embedded in the national culture, and vice versa – the works that were considered as reflective of nationalist discourses served as a meeting point for diverse viewpoints to emerge. Hence taking into account encounters with memories was important for showing that contingent futures of memory emerge from established views and openings to difference.

How does your work on Asia Minor memories connect to current global debates over contested pasts and refugeehood?

While this is not a new phenomenon, the declared refugee crisis in 2015 brought this issue to the foreground of European politics. Returning to the case of refugees from Asia Minor in this context, offers an interesting point of departure for considering what meanings of refugeehood persist when the initial sense of emergency and crisis that led to it are long gone.

Looking into the ways in which contemporary identity politics intertwine with questions about the past, and how claims of ownership over this past inevitably come endowed with specific demands for the future, resonates strongly with debates taking place in other global contexts, be it on exclusions and inclusions that characterize commemoration practices or the role of migratory heritage within national culture. Finally and importantly, the compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey served as a blueprint for executing a number of other displacements, most notably after World War II, and exploring those links offers a vantage point for viewing the legacies of war in the global context, beyond Greece and Turkey. I have made some steps in exploring the latter in my most recent work.

Your current research project deals with Greek comics and graphic novels. How did you get from researching memories of Asia Minor to comics?

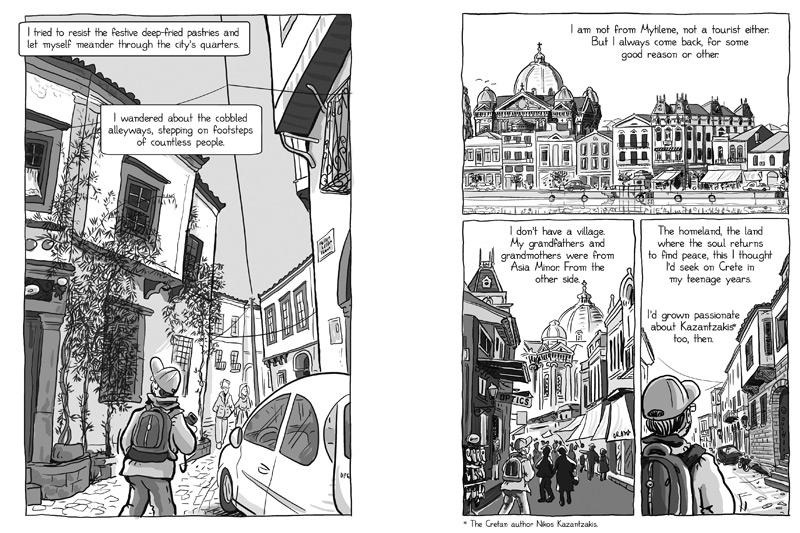

Just as I was starting my research project on memories of Asia Minor, as part of my doctoral dissertation at the University of Oxford in 2014, Soloup’s graphic novel Aivali was published. I found it very engaging and particularly reflective of the ways in which the grandchildren of refugees relate to their cultural heritage. Just think of your own family memories: rarely they come as a full story, and much more often – as fragments, prompted by something in our everyday. It is then our task to piece those fragments together. This is a process which is often facilitated by delving into the archive to fill in the gaps in the story as well as a journey of return to the homelands of one’s ancestors. This is exactly what we see happening in the case of Soloup’s Aivali, but also other recent works on the topic.

The graphic novel is a particularly apt format to represent what dealing with a difficult historical past and what tis entails, which can be seen from the proliferation of such narratives across the globe. Graphic narrative is built around a number of tensions; between word and image, between single image and page as a whole, between representing and exposing the process of mediating representation. What is more, they often break down linear historical chronologies and as a result mange to expose history as a process with long lasting consequences beyond the event itself. The capacity of the comics medium to render history is what caught my initial interest and eventually led me to the wider exploration of comics and graphic novels as a means of artistic innovation and social critique in contemporary Greece, first conceived while on a postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton University, and currently continuing within the framework of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie individual fellowship, held at the University of Amsterdam.

You are one of the coordinators of the project Greek Studies Now. Could you tell us more about this project? What are the stakes for Modern Greek Studies in the current cultural conjecture?

Greek Studies Now started as an initiative between the University of Oxford and the University of Amsterdam in 2020, with Durham University joining as a third institutional partner in 2023. Yet from the very beginning it served as a network bringing together colleagues across different universities and career stages. The key question that this network addresses is how Greek studies can offer a vantage point for critical engagement with wider global contexts and debates. Over the course of three years since this network’s inception, the topics that were addressed in this framework ranged from eco-criticism to the trial of the Golden Dawn, from AIDS commemoration to Albanian-Greek identity, and much more. At the core of the network’s activities lies an invitation to think contrapuntally – weaving connections across topics, contexts, and disciplinary boundaries. Most importantly, I believe this kind of critical engagement with the present also invites reconsideration of one’s own role and positionality as a researcher. While this is certainly a much wider call, I see more and more colleagues who are active participants in the network activities to think through and engage with their research topics in various ways beyond academia.

Read also from Greek News Agenda:

Reading Greece: The Asia Minor Catastrophe in Modern Greek Literature

* Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

TAGS: ASIA MINOR | DIASPORA | GRAPHIC NOVELS | LITERATURE & BOOKS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES | REFUGEES