Panagiotis Roilos is George Seferis Professor of Modern Greek Studies and of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. Professor Roilos’s wide-ranging research interests include Greek literature (from antiquity to the present), European aestheticism (with a focus on Greek and British literature), the Enlightenment, German Romanticism and the Classics, premodern and modern critical theory, historical and cognitive anthropology, philosophy and rhetoric, comparative oral poetics, diaspora, and cultural politics. In 2022, Prof. Roilos was elected President of the European Cultural Centre of Delphi.

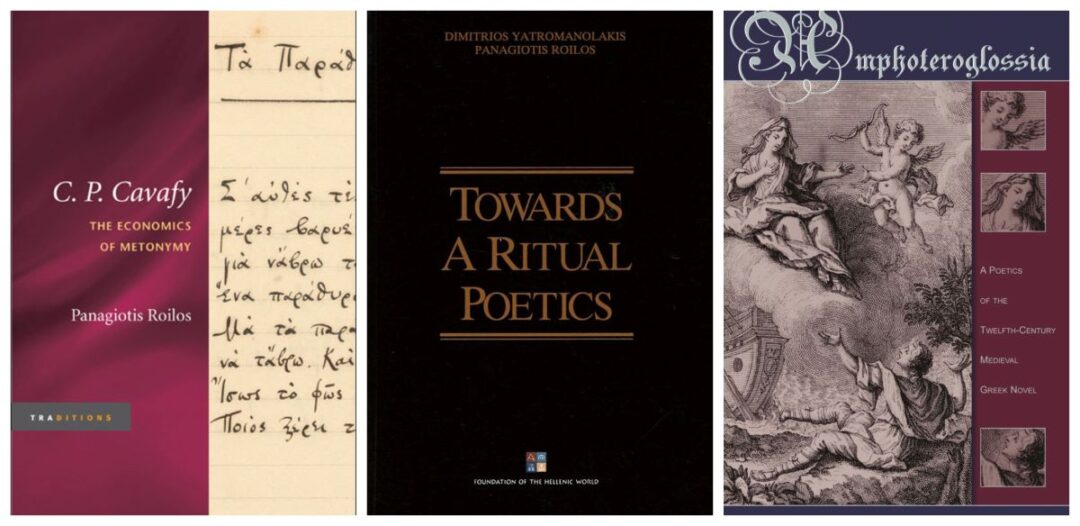

Among his major publications are the books C. P. Cavafy: The Economics of Metonymy (2009), Amphoteroglossia: A Poetics of the Twelfth-Century Medieval Greek Novel (2005), and Towards a Ritual Poetics (2003; co-author with D. Yatromanolakis). His current book-length projects include “Abducting Athena: The Nazis and the Greeks” and “Neomedieval Metacapitalism”.

Professor Roilos spoke to Rethinking Greece,* on issues as varied as the formation of modern Greek identity during the 16th century, Cavafy’s idiosyncratic discourse, Nazis’ appropriation of Greek antiquity, the unprecedented impact AI will have on political institutions, our language as a bastion against hegemonizing tendencies, the present and future of Modern Greek Studies, and finally, on his plans for this year’s Delphi Dialogues.

You’ve suggested that the roots of modern Hellenism can be traced back to the 16th century. Could you expand on the historical elements that mark this period as a starting point?

Let me repeat what I have written in one article on the topic. There, I have argued the following: “The Fall of Constantinople gave rise to, or rather accelerated, an intense process of what, adapting Gregory Bateson’s concept of “schismogenesis” to the Greek case, I would call the ‘schismogenetic formation of early modern Greek ethnic and cultural identity.’ This transitional process unfolded when Greek Orthodox populations of the former Byzantine Empire, especially the Greek speaking ones, would gradually forge, or rather further corroborate, a sense of a common cultural and historical heritage, probably of a distinct ethnic identity, too, by strongly counter-distinguishing themselves from what at the time they perceived as their quintessentially cultural and ethnic “other,” the Ottoman Turks.” Already in the late 15th c. and throughout the 16th and 17th c. Greek intellectuals, mainly of the diaspora, cultivated a cultural politics that aimed at 1. promoting the view that contemporary Greeks are the legitimate heirs to classical antiquity and 2. on the basis of this valuable cultural capital, instigating (and at times co-ordinating) the Philhellenic sentiments (occasionally, initiatives, too) of their European interlocutors. In that sense, I have contended that the educational and cultural political movement orchestrated mainly by Adamantios Korais and his associates finds a significant parallel in the 16th century, a parallel that is unfortunately almost entirely neglected in recent and current scholarship.

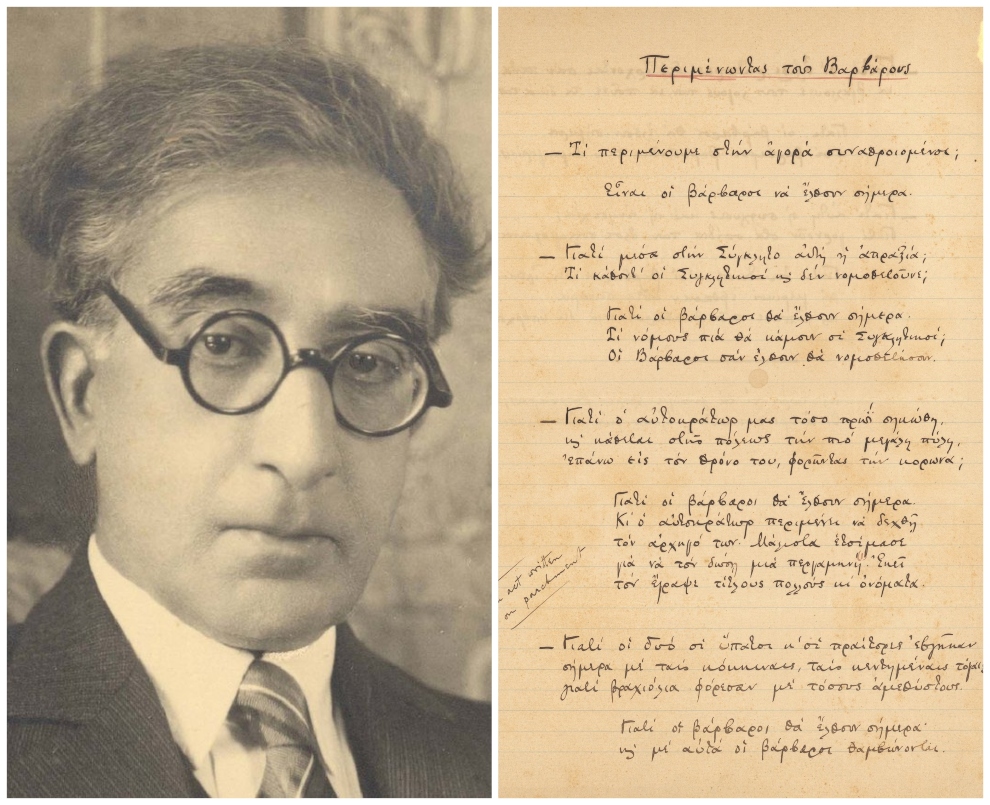

You’ve written extensively on C.P. Cavafy, including your book “The Economics of Metonymy”. What do you find most enduring about Cavafy’s poetry? What do you think of modern approaches that examine his work through lenses like queer theory?

All approaches are legitimate and welcome to the extent that they do to not lay claim to Cavafy’s own work and thought, or to absolute and exclusive interpretive authority. Queer theory can provide very interesting insights into Cavafy’s poetry and ideology; in fact, it has done so in certain cases. In the book you mention I discuss systematically and holistically Cavafy’s idiosyncratic economic ideas, sexuality, poetic and ideological discourses. Cavafy developed a discourse that, by adopting “prosaic” discursive modes and promoting what I call “liminal” themes, transcended his contemporary poetic and ideological restrictions. This is what in general makes his poetry especially topical even today.

Your project “Abducting Athena,” on the Nazis’ appropriation of Greek antiquity for their own cultural propaganda sounds fascinating. Could you give us a preview this study? How you believe it can inform the way we approach classical Greece?

This is the topic of a course I’ll offer at Harvard this coming spring. The barbaric arbitrariness of the sustained “state of emergency” that consolidated and promoted the Nazi regime involved a monstrous misrepresentation and abuse of the cultural capital of aspects of Greek antiquity. It constitutes a frightening example of how racism, sexism, populism, ultra-nationalism, the barbaric dogma of “white supremacy” may be complemented and “validated” by a propagandistic, systematic appropriation and misinterpretation of cultural and historical heritage with a view to manipulating and controlling huge parts of the population, to rendering them to a homogenized and disenfranchised mass.

You are currently completing a book on digital post-humanism and democracy entitled “Neomedieval Metacapitalism,” which is concerned with the impact of the prevalence of technology and AI in our modern democracies. What challenges does post-humanism pose for democracy?

In this book I explore in detail the concept of “neomedieval metacapitalism,” which I introduced in articles and lectures several years ago. I have put forward this concept to describe what, to my mind, constitutes an important—but by and large unnoticed—paradox: the persistence in the fourth industrial revolution of deep structures of thought that are supposed to go back or be similar to corresponding perceptual patterns usually associated with the Middle Ages. To repeat what I have argued elsewhere: “By and large the digitization of many sectors of human interaction and their restructuring with the help of AI often entail the distancing of individuals from their surroundings, from their world, and from nature itself, while also developing a sense of an essentially non-transcendental reality which, paradoxically, transcends individual perceptual abilities and purviews—hence its quasi-metaphysical character.”

This marks a cosmogonic development in the history of humanity, which will have an unprecedented impact on the ways in which political institutions operate and on civil and human rights. Especially democratic polities have no excuse to not protect those rights from their potential subversion and restriction entailed by the accumulation of technological, and concomitant political and economic power, in the hands of the few ones who have access to centers of decision-making in these sectors.

What is your perspective on the current state and future direction of Modern Greek Studies in U.S. universities? What are emerging opportunities or challenges you feel will shape the field in the coming years?

Modern Greek Studies should dynamically and confidently converse with other fields, including developments in major current developments in cultural theory. Such creative dialogues should not neglect the comprehensive study and teaching of all centuries of modern Greek culture and history. Presentism is by no means an interpretive, scholarly, or educational panacea. Just the opposite: it’s an easy, more often than not simplistic, and potentially dangerous “solution.”

You are the President of The European Cultural Center of Delphi. Your initiative, the Delphi Cultural Dialogues, have become a vital part of the Center’s programming. How did it come to life, and what are the key goals you aim to achieve through these dialogues? Could you share any themes you’re excited to explore in the Delphi Cultural Dialogues 2025?

It was a great honor and responsibility for me to succeed Professor Hélène Ahrweiler, an iconic academic figure in Europe, to the Presidency of that prestigious European Cultural Center. My main goal has been to make Delphi a “navel” of contemporary culture and thought. The Delphi Dialogues is one of the new international institutions I recently established. They aim at shedding new light on thorny and pressing issues that our world is facing today: for instance, AI and Democracy, technology and culture, environmental crisis, refugee crisis, etc.

Every summer some of the world’s leading and most impactful thinkers and scholars come to Delphi and engage in highly original, cross-disciplinary dialogues. The Delphi Dialogues have began to establish themselves as a major international institution in contemporary thought. Their global impact has so far been immense: I should only note that the Second Delphi Dialogues were watched online by more than 190.000 (one hundred ninety thousand) people from all over the world!. This coming summer the Third Delphi Dialogues will focus on biopolitics, bioethics, and democracy.

In an increasingly globalized world, how do you see modern Greek culture and identity evolving? Are there unique contributions or challenges Greece faces in navigating its identity on an international stage?

No “identity” is, can, or should be “pure.” And, to a great extent, almost all sorts of “identity” tend to be constructed, habitually formed, adopted, and performed. This also means that in general there is nothing by definition “unique” or “exclusive” to the challenges that Greece is facing in today’s globalized world. To my mind, one of the most pressing cultural challenges that very many parts of the world today, Greece included, face is the threat of cultural (and, as a result, ideological, behavioral, and sociopolitical) homogenization and hegemonization mainly by dominant, i.e. Anglosaxonic, cultural industries and modes of thought. As a vehicle not only of practical communication but also of what I call “historical and cultural mythemes,” language constitutes a powerful bastion against such hegemonizing tendencies.

* Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi

* Featured photo © AMA-MPA

Read also from Greek News Agenda:

- Rethinking Greece|Katerina Lagos and Vangelis Calotychos of the Modern Greek Studies Association on cultural shifts and research trends in Modern Greek Studies

- 7th European Congress of Modern Greek Studies: “Modern Hellenism: texts, images, objects, histories”

- Reading Greece: Vassilis Lambropoulos on New Greek Poetry and Modern Greek Studies

TAGS: HELLENIC STUDIES | LITERATURE & BOOKS | MODERN GREEK STUDIES