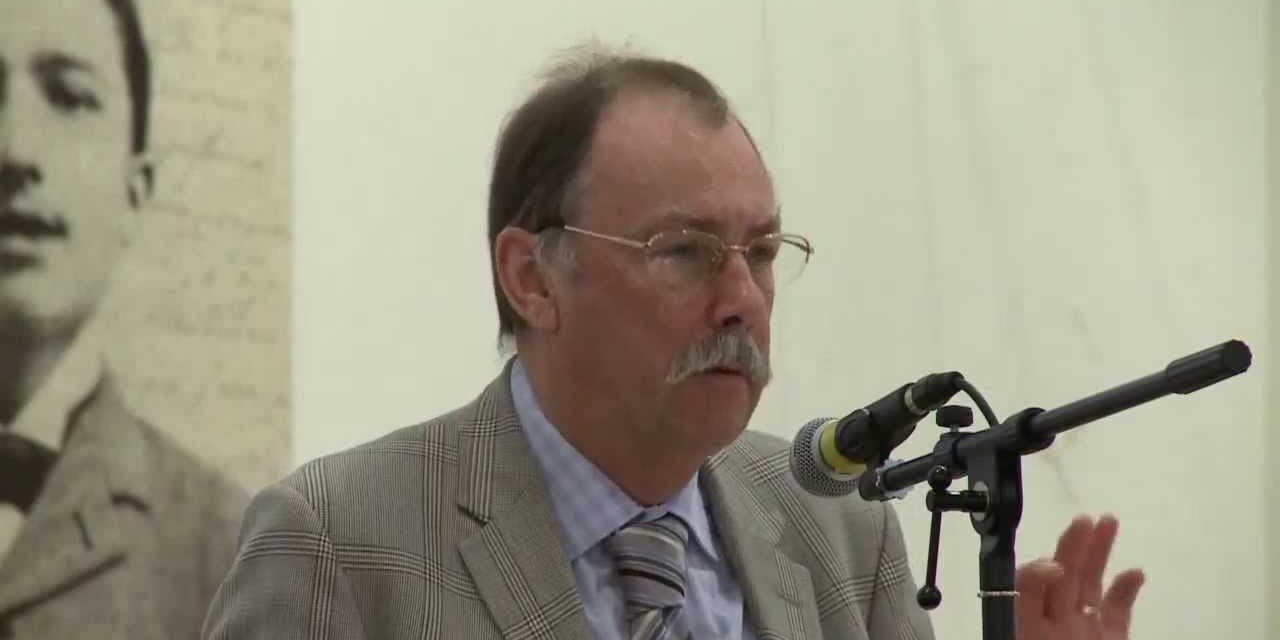

Roderick Beaton is Koraes Professor of Modern Greek & Byzantine History, Language & Literature, Director of the Centre for Hellenic Studies at King’s College London and Fellow of the British Academy. His research spans Greek literature, history, and culture from the 12th century to the present; classical reception in the formation of late medieval and modern Greek identity; and the Greek novel since antiquity.

Professor Beaton’s principal publications include Byron’s War: From the Romantic Imagination to the Greek Revolution (2013) [winner of the Anglo-Hellenic League’s Runciman Award 2014], The Making of Modern Greece: Romanticism, Nationalism and the Uses of the Past (edited, with David Ricks, 2009), George Seferis: Waiting for the Angel. A Biography (2003) and An Introduction to Modern Greek Literature (1999).

King’s College London is one of only two British universities that have an established professorship in Modern Greek. The Koraes Chair was established at King’s in 1918.

Professor Beaton spoke to Rethinking Greece* about the study of Greece internationally, Greek national identity, Greek exceptionalism and the Greek achievements in the last two hundred years:

Since August 2015 the King’s College Department of Classics merged its teaching and research supervision with the Centre of Hellenic Studies forming a single unit for the study of Greece and the Greek World. Can you tell us more about the history of Greek studies at King’s, the Koraes Chair and its prospects?

Ancient Greek has been taught and studied at King’s since the College first admitted students, in 1831 – just at the time when Greece itself was first recognised as an independent sovereign nation. Then in 1918 the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek History, Language and Literature was added. In the 1970s this in turn became the nucleus for the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, which functioned until 2010, and was responsibile for teaching up to 40 students per year at all levels from beginners in modern Greek language to PhD students. Many of its alumni are now in distinguished positions in Greek universities – others include the Athens correspondent of The Guardian and the current UK ambassador to Greece. Recent years have seen a steep decline in the number of undergraduate students in UK universities specialising in modern foreign languages; degree programmes in Modern Greek are no longer sustainable. But at the same time there has been an impressive rise in the number of students wishing to study individual courses (within a programme of study in e.g. English, History, Comparative Literature or Classics) in which they are introduced to the history, language and literature of modern Greece. The study of Byzantium continues to flourish within our department of Classics and also of History. The key position in all these developments is the Koraes Chair, which will soon be celebrating its first hundred years. The College has recently launched an appeal to foundations and interested individuals to raise 1.64 million pounds to ensure its future for the next hundred years. Thanks to generous sponsorship, almost one third of this target has been reached already.

Greek national identity constitutes a focal point of your recent academic interests and work. What is the importance of the Greek national experience and how does it relate to Europe and other European nation states? In what ways literature contributes to the formation of national identity in Modern Greece?

Greek national identity constitutes a focal point of your recent academic interests and work. What is the importance of the Greek national experience and how does it relate to Europe and other European nation states? In what ways literature contributes to the formation of national identity in Modern Greece?Greece was the first new nation-state to be established anywhere in Europe after the upheavals of the Napoleonic wars, recognised by an international protocol of 1830. All other modern nation-states have followed the example of Greece. People don’t realise this, because the Greeks, and their foreign supporters, were so eager to present their achievement as something different from what it was, as the return to an ancient past. But modern Greece (the nation-state created out of the Revolution of the 1820s) I believe is a new creation, not a revival at all. The story of nation-states in the world today begins with that achievement of the 1820s in Greece. It’s a cliche to say that modern Europe is indebted to ancient Greece (because all our culture began from there); but Europe owes a debt to modern Greece too, to those who fought to set Greece free and all those (both Greeks and foreigners) who have consolidated that achievement ever since. Because, as the historian Paschalis Kitromilides has argued, Greece represents the ‘paradigm nation’, the one that, historically speaking, set the example that all others have followed since.

“Zorba the Greek” is an archetype of Greekness originating from Nikos Kazantzakis oeuvre. How has this influenced the image of Greek identity beyond literature? To what degree Kazantzakis incorporates a modernist approach in his oeuvre and how does this resonate with European modernism?

Zorba is an odd representative of ‘Greekness’ – ‘the Greek’ isn’t even part of the book’s Greek title. It was thought up by a translator who was helping Kazantzakis in his efforts to win the Nobel prize. And in the film which is even more famous than the book, neither of the two male leads is played by a Greek actor. So Zorba, in reality, isn’t that ‘Greek’ at all. On the other hand the book, the film, and Theodorakis’ music for the soundtrack, have all become world-famous, and in doing so have created a partly false idea of Greek identity. That said, Kazantzakis himself was profoundly conscious of his own identity as a Greek, and much of his writing does explore that in much more serious ways. He also projected a very specific Cretan identity, based on the history, language and culture of his native island. According to Kazantzakis, Crete lies at the meeting point of three great continents: Europe, Africa and Asia, and its people represent a unique and creative mingling of the three. As a writer he was influenced by all the great movements of modern European literature, including Romanticism and Modernism. I believe that the Modernist, experimental side of Kazantzakis’ writing has not been given the recognition it deserves. He was a fearless innovator, and I would suggest that some of his work even hints towards the Postmodernism that would develop worldwide during the 1970s, after his death.

What is the Byron’s legacy to the present-day Greece? Are there continuities or ruptures between 19th century Greece and today’s prospects and dilemmas?

Byron was the most famous of those outsiders who came to Greece during the Revolution – philhellenes, as they were called – because they believed in political freedom and saw Greece as the place where that freedom could become a reality. Byron himself went further, and even foresaw that the Greeks would develop a whole new kind of politics, that would then be emulated by the rest of the world. In a way, though not quite as he envisaged it, that is what has happened, as all other nation-states in Europe have followed in the footsteps of Greece in achieving national self-determination and unification. The heroic legend of his willing self-sacrifice for the cause of freedom in Greece played its part in securing victory for the Greeks, and is an enduring part of what we might call the ‘national myth’ of Greece today. But Byron’s more fundamental legacy lies in the way Greece’s political relationships have developed, ever since his own day. Byron was one of those who insisted on sound diplomatic and economic relations with other states. He embarked upon a pragmatic campaign to win power for a government in Greece, based on democratic principles and above all on the rule of law. He was not alone in that, of course, but his voice and influence empowered those Greeks, such as his friend and associate Alexandros Mavrokordatos, a later prime minister of Greece, to steer the country in the direction that we know today – with all the problems that that entails, particularly in recent years.

How does the current crisis affect contemporary Greek poetry, prose and artistic output, in general?

How does the current crisis affect contemporary Greek poetry, prose and artistic output, in general?This question has just been addressed in a book of essays published in English, mostly by leading Greek prose-writers, edited in 2015 by Natasha Lemos and Eleni Yannakaki, Critical Times, Critical Thoughts. The editors argue that literature doesn’t just reflect the reality of times such as these, but also by its nature has a transformative power. Exactly how literature will be seen, in hindsight, to have transformed the present crisis is very hard to see right now. It’s a process that takes time, and no one knows how the crisis will end or what further horrors it may bring in its train. Even a year ago, nobody could have foreseen that migration across the Aegean would have reached the levels it has today. If it seems facile to suggest that literature can ‘solve’ intractable problems like these, we should nonetheless think of something that Byron wrote, almost 200 years ago: ‘But words are things, and a small drop of ink … produces / That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think’. And more tendentiously, his friend the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, another philhellene, wrote that ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.’ It’s not obvious how – but there’s hope for writers and literature yet!

In what terms can we rethink Greece and Greek exceptionalism after six years of intense economic and political crisis and the relevant European debates?

Well, for what it’s worth I’ve always thought that Greek exceptionalism (the idea of treating Greece and Greeks as a special case, set apart by a uniquely long history) has been part of the problem, not part of the answer. Not being Greek myself I’ve no right to prescribe how Greeks ought to define themselves. But I do believe that the opportunity to take a justified pride in the achievements of modern times might become part of a solution when Greece does finally begin to pull itself out of crisis. I’ve already spoken about the achievement of a brand-new nation state in the early 19th century, one that has proved an enduring model for others. Another would be Greek shipping – the wealth it has generated, and the lasting influence too, through the charitable and educational foundations set up in memory of the great ship-owners of the last century, men like Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos. And what about Greek achievements in the arts in the 20th century: Nobel prizes for Seferis and Elytis, the worldwide fame of Kazantzakis and Cavafy; musicians like Hadjidakis and Theodorakis; artists like Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, Theophilos, Engonopoulos. And these are just a few. It’s not just the Acropolis, the Parthenon, the endless reproductions of red-figure vases and miniature sculptures that you see in tourist shops all over Greece: the ancient past is part of the story, of course it is. But that’s an old story. The new story that needs to be told is how much Greeks have achieved for themselves in the last two hundred years or so.

*Interview by Aikaterini Papalouka & Nikolas Nenedakis

Read more: Professor Roderick Beaton’s full research profile; Modern Greek Studies since 1975: A personal retrospect; Listen: The Greek Crisis: How did we get here? A talk by Professor Roderick Beaton recorded in 2 October 2015

Roderick Beaton, speaking on “Zorba and the Greeks: Nikos Kazantzakis and the Greek Tradition” (Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957): The Luminous Interval, International Symposium on the occasion of the 130th anniversary of the birth of Nikos Kazantzakis, London, 2013):

See also: UK’s Society for Modern Greek Studies; John Kittmer, UK’s Ambassador to the Hellenic Republic: Gennadius, the Koraes Chair and the state of Modern Greek in Britain

TAGS: CRISIS