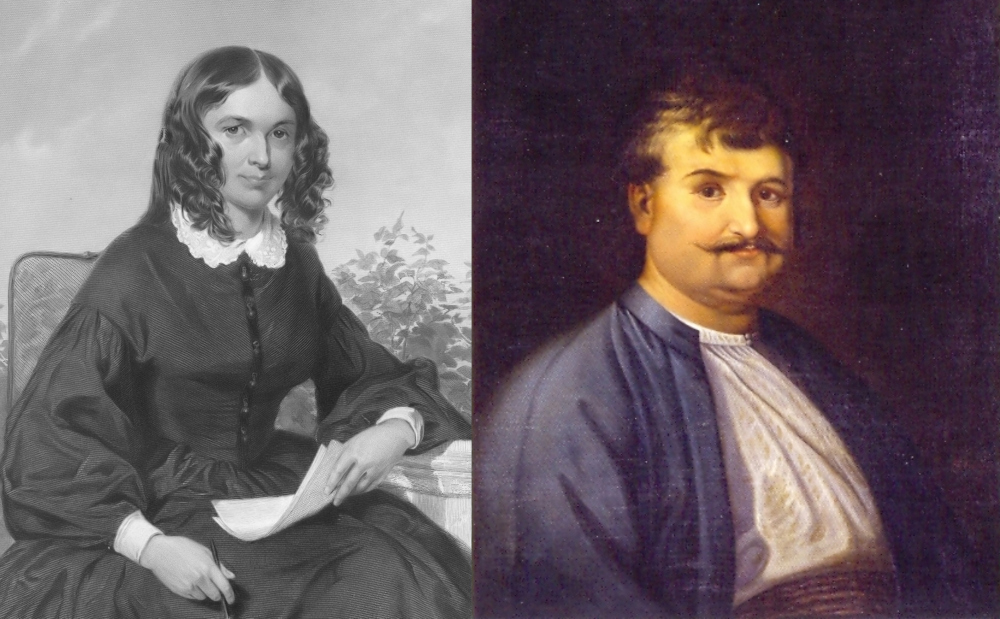

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) was an English poet of the Victorian era, considered to be one of the most internationally influential 19th-Century English authors. She was held in higher critical esteem than any other female poets of the English-speaking world in the 19th century, and her poems reflected her humanistic and liberal views, addressing subjects such as the Atlantic slave trade, child labour in England, reactionary Austrian control in Italy, and the question of women’s roles and rights.

Her commitment to writing about social and political concerns was evident since the beginning of her career, as her first published poems, which appeared in journals in 1821-24, were written about the ongoing Greek War of Independence and particularly celebrated Byron’s part in the campaign. In her collection An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems, published in 1826, we find the poem “Riga’s Last Song”, inspired by one of the first heroes of the Greek struggle, who put all his efforts in the Greek cause and died for it years before the declaration of the Greek Revolution: Rigas Velestinlis. Often characterised as “the proto-martyr of the Greek Independence”, he was widely influential both in his lifetime and after his death in 1798.

Life and death of Rigas

Rigas Velestinlis, also known as Rigas Feraios (sometimes transliterated as Rhigas Pheraios), and often referred to simply as Rigas, was a writer, thinker and one of the most notable and influential figures of the Modern Greek Enlightenment. He was born (likely in 1757) into a relatively wealthy family in the village of Velestino (Central Greece).

His birth name has never been confirmed, although some suggestions have been made. His first name was seemingly Rigas (which means “king”); he always signed his writings either by his first name alone or as Rigas Velestinlis, a surname he gave himself, meaning “native of Velestino”. 19th-century Greek scholars would usually refer to him as Feraios, which is basically an “archaisation” of the word Velestinlis, since the village of Velestino was situated in the area known as Pherae in antiquity; this name has hence become more prevalent, although Rigas never used it for himself.

Rigas (along with Adamantios Korais) depicted in Greece reborn by Theophilos (1911)

Rigas (along with Adamantios Korais) depicted in Greece reborn by Theophilos (1911)

Details about the first years of his life are scarce; he received an education and became a teacher in another village; he is believed to have killed an Ottoman kodjabashi in Velestino, then seeking refuge in a village of Mount Olympus. He later went to stay in a monastery of Mount Athos, and then in Constantinople, where he received further education and was accepted in the circles of the Phanariots. From there, he would go first to Iași and then Bucharest, where he took up more languages and eventually became a clerk for the Wallachian Prince Nicholas Mavrogenes.

Learning about the French Revolution, he developed hopes that an uprising of this sort could take place in the Balkans; working as dragoman (interpreter/guide) at the French consulate in Bucharest, he wrote a Greek version of La Marseillaise, later made famous in English through Byron’s translation. Around 1793, he settled in Vienna, then home to a large Greek community, in hopes of contacting Napoleon Bonaparte for assistance in a Balkan resurgence. While in the city, he edited a Greek-language newspaper, Efimeris.

Left: Statue of Rigas in front of the University of Athens (by C messier via Wikimedia Commons); Right: Statue of Rigas in Belgrade (by George M. Groutas via flickr)

Left: Statue of Rigas in front of the University of Athens (by C messier via Wikimedia Commons); Right: Statue of Rigas in Belgrade (by George M. Groutas via flickr)

A champion of republicanism, he wrote political pamphlets based on the principles of the French Revolution, poetry and translations of foreign works. Arguably his most famous poem was the battle-hymn Thourios (1797), were he urged the Greeks to rise against Ottoman rule.

The Austrian authorities were tipped off about his activities and spreading of revolutionary ideas, and he was arrested at Trieste in December 1797, interrogated and sent back to Vienna. In May 1798, he was handed over to the Ottoman governor of Belgrade, along with several of his accomplices. Despite several important figures pleading for their lives, the prisoners were eventually strangled and thrown to the waters of the Danube on 24 June 1798, supposedly because they were trying to escape.

Due to his passionate calls for action and his enthusiastic poems, as well as his torturous death, Rigas became a powerful symbol of resistance for Greeks and Philhellenes.

Riga’s Last Song

I have looked my last on my native land,

And over these strings I throw my hand,

To say in the death-hour’s minstrelsy,

Hellas, my country! farewell to thee!

I have looked my last on my native shore;

I shall tread my country’s plains no more;

But my last thought is of her fame;

But my last breath speaketh her name!

And though these lips shall soon be still,

They may now obey the spirit’s will;

Though the dust be fettered, the spirit is free –

Hellas, my country! farewell to thee!

I go to death—but I leave behind

The stirrings of Freedom’s mighty mind;

Her voice shall arise from plain to sky,

Her steps shall tread where my ashes lie!

I looked on the mountains of proud Souli,

And the mountains they seemed to look on me;

I spoke my thought on Marathon’s plain,

And Marathon seemed to speak again!

And as I journeyed on my way,

I saw an infant group at play;

One shouted aloud in his childish glee,

And showed me the heights of Thermopylæ!

I gazed on peasants hurrying by,—

The dark Greek pride crouched in their eye;

So I swear in my death-hour’s minstrelsy,

Hellas, my country! thou shalt be free!

No more!—I dash my lyre on the ground—

I tear its strings from their home of sound—

For the music of slaves shall never keep

Where the hand of a freeman was wont to sweep!

And I bend my brows above the block,

Silently waiting the swift death shock;

For these lips shall speak what becomes the free—

Or—Hellas, my country! farewell to thee!

He bowed his head with a Patriot’s pride,

And his dead trunk fell the mute lyre beside!

The soul of each had past away—

Soundless the strings—breathless the clay!

(Taken from the EBB Archive)

Plate in front of Nebojša Tower in Belgrade, where Rigas was held ahead of his execution

Plate in front of Nebojša Tower in Belgrade, where Rigas was held ahead of his execution

The poem is structured in the form of a monologue; Barrett Browning imagines Rigas bidding farewell to his country, lauding its natural beauty and rich history, before being executed. In the last verse, it changes into a third-person narrative, presenting Rigas ready to be executed (although the description alludes to a beheading, rather than a strangulation, possibly because the poet was not aware of the exact circumstances of his death).

The poet references Souli, a mountainous area in Epirus known for its inhabitants’ resistance against the local Ottoman lords. She also mentions Marathon and Thermopylae, the sites of arguably the most iconic battles of Ancient Greeks against intruders. Barrett Browning was deeply inspired by the Battle of Marathon, using it as the subject of her first published poem (privately printed), The Battle of Marathon, which she wrote at the age of fourteen.

Read also via Greek News Agenda: POEM OF THE MONTH: “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year” by Lord Byron; POEM OF THE MONTH: “The Free Besieged” by Dionysios Solomos; POEM OF THE MONTH: “Hellas” by Percy Bysshe Shelley; BOOK OF THE MONTH: “The Archipelago on Fire” by Jules Verne

Ν.Μ. (Intro image: Left, Portrait of Elizabeth Barrett Browning ; Righ, Portrait of Rigas Velestinlis by Andreas Kriezis)

TAGS: HISTORY | LITERATURE & BOOKS