On May 26-27, there took place the Third Workshop on ‘Romeyka and the languages of the eastern Black Sea‘ at Queens’ College, Cambridge. Romeyka [Muslim Pontic Greek, Rumca] is the last surviving variety of Greek spoken in north-eastern Turkey, in the area traditionally known as Pontus.

History

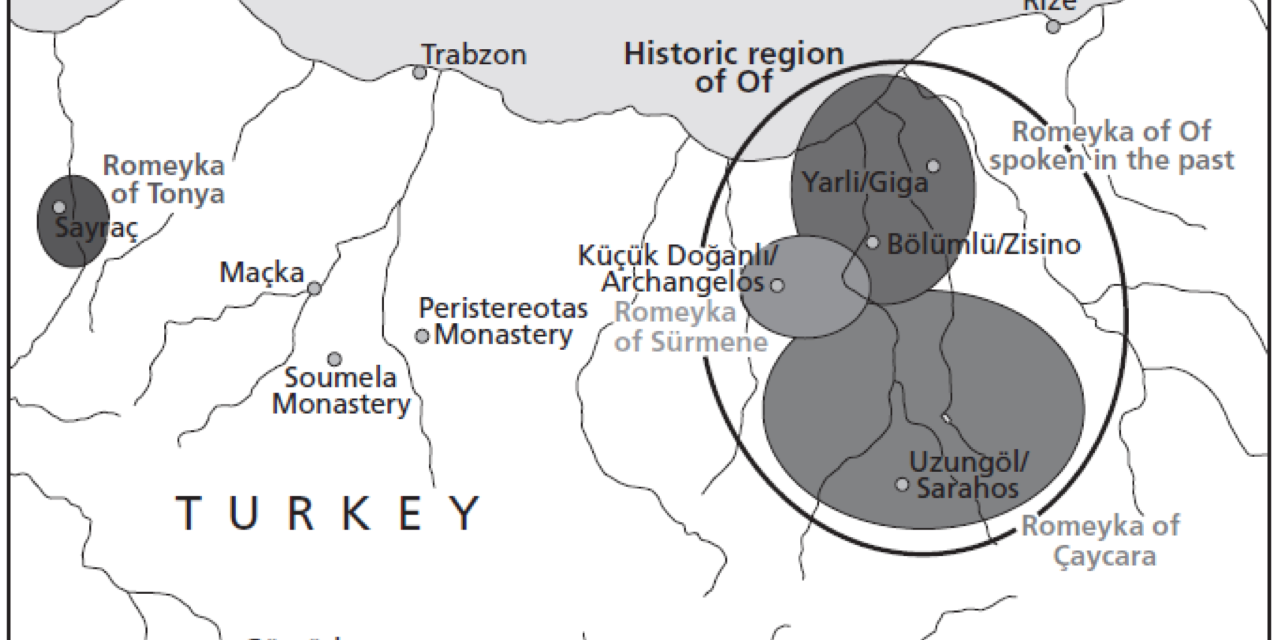

Islamisation of Greek speakers in the areas of Of, Sürmene, Rize, and Matsouka, is reported in the 15th-18th centuries. The Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey, which occurred under the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, saw all Orthodox Christians of Asia Minor relocate to Greece and all Muslims of Greece relocate to Turkey. With religion as the defining criterion, Greek-speaking Muslims were allowed to stay in their Asia Minor homeland, but Greek-speaking Christians had to leave Pontus, thereby explaining why Greek survives only in small enclaves in this area.

Currently, there are three remaining Greek-speaking enclaves: Of (Çaykara), Sürmene, and Tonya. With the exception of Greek spoken by Orthodox Christian inhabitants of Turkey (mostly living in Istanbul and Imbros/Gökçeada), Romeyka is the last surviving variety of Greek spoken in eastern Turkey today. All other Asia Minor varieties such as Cappadocian are no longer spoken in Turkey.

Yet, repeated waves of emigration from Trabzon, coupled with the influence of the dominant Turkish-speaking majority, have left the dialect vulnerable to extinction. Romeyka has been classified as “definitely endangered” by UNESCO and as “severely endangered” by the Encyclopaedia of the World’s Endangered Languages. It is under serious danger of becoming extinct through further contact with Turkish, which is the major language of the community. Most importantly, Romeyka is under threat of becoming extinct because children no longer speak it.

The Romeyka Project

Led by Ioanna Sitaridou, in collaboration with Professor Peter Mackridge, who has carried out pioneering research on Pontic dialects since the 1980s and a team of collaborators, the Romeyka project aims to document this endangered Greek variety spoken in north-East Turkey, on which very little is known and whose investigation is of extreme urgency because of the small number of native speakers who acquire it as a first language.

The overarching aim of the project is to study the evolution of Romeyka within the broader context of Asia Minor Greek. Given the lack of sufficiently old textual evidence, which would normally provide clues as to the evolution of the Greek language, Romeyka can be used as a ‘window on the past’ to better understand the latter. ‘With as few as 5,000 speakers left in the area, before long Romeyka could be more of a heritage language than a living vernacular,’ says Dr Sitaridou. ‘With its demise would go an unparalleled opportunity to unlock how the Greek language has evolved. ’

Funded by Cambridge and Princeton Universities and the British Academy, the project has established an international reputation which can be seen through our production of research papers, invited and conference talks and organisation of workshops.

Language Evolution

Romeyka is proving a linguistic goldmine for research because of the startling number of archaic features it shares with the Koiné (common) Greek of Hellenistic and Roman times, spoken at the height of Greek influence across Asia Minor from the 4th century BC to the 4th century AD. ‘Although Romeyka can hardly be described as anything but a Modern Greek dialect,’ explains Dr Sitaridou, ‘it preserves an impressive number of grammatical traits that add an Ancient Greek flavour to the dialect’s structure – traits that have been completely lost from other Modern Greek varieties.’

Dr Sitaridou’s research is ultimately trying to pinpoint how Romeyka evolved. ‘We know that Greek has been continuously spoken in Pontus since ancient times and can surmise that its geographic isolation from the rest of the Greek-speaking world is an important factor in why the language is as it is today,’ she says. Nevertheless, Romeyka also demonstrates considerable innovation especially as a result of contact with Turkish. In this respect, Dr Sitaridou is interested in modelling what influence the contact with Turkish and Caucasian languages has had on the evolution of the dialect. Given the linguistic and socio-historic context of Romeyka, she notes that ‘in Pontus, we have near-perfect experimental conditions to assess what may be gained and what may be lost as a result of language contact.’

The implications of such research are, however, far more pervasive, since understanding how language functions could provide some insight into cultural identity and people’s sense of themselves, as well as what happens when cultures connect. Dr Sitaridou, whose own great-grandparents were from the region, believes that the linguistic evidence will help to unravel the thread of language evolution.

TAGS: GREEK LANGUAGE