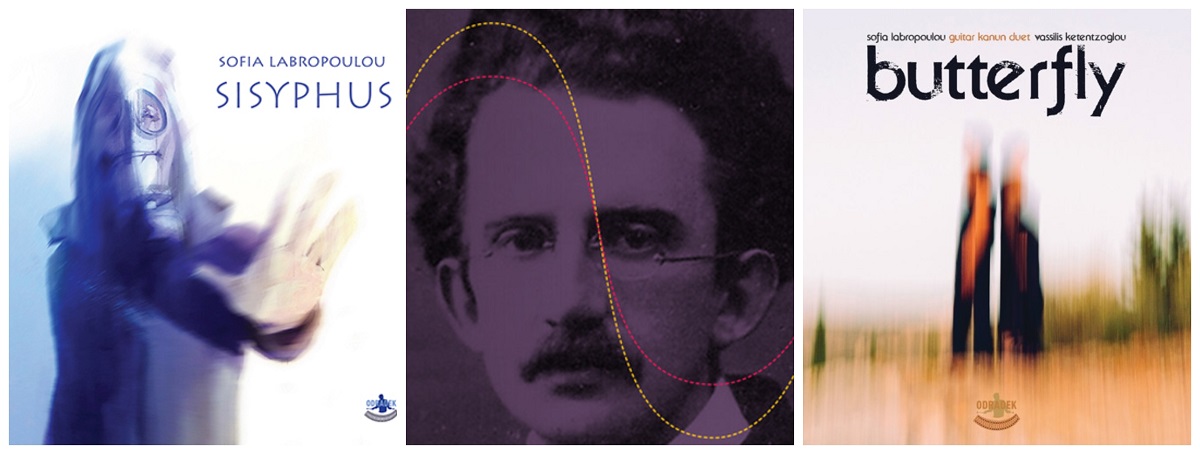

Sofia Labropoulou is a kanun player and composer who merges the worlds of Greek and Mediterranean folk, classical Ottoman, western medieval, experimental and contemporary music. After eight years of playing together with Vassilis Ketentzoglou, they released as Guitar Kanun Duet their first album “Butterfly” in 2019. Labropoulou’s first personal album “Sisyphus” was released in December 2020 by Odradek Records to both critical and commercial success as it reached no. 2 in the Balkan World Music Chart and was selected among the best ten records of 2021 by World Music Charts Europe. Sisyphus is a collection of Labropoulou’s own compositions, inspired by an eclectic range of literary and musical sources and featuring a rich ensemble including kanun, shepherd’s flute, oud, santur, kemençe as well as Western instruments such as clarinet, cello and double bass.

Labropoulou spoke to Greek News Agenda* about how she came to study the kanun, the genre of “world music”, her love of poetry and how she combines her varied musical influences, her latest album Sisyphus, the literary heros of Albert Camus’ “Sisyhpus” and Kostis Palamas‘ “O Γκρεμιστής” [the Demolisher] that occupy it, and what they can teach us about not losing our connection to earth and memory.

What led you to chose to study the kanun, a very special traditional instrument of the Middle East?

I started studying piano and classical music at a very young age. I was lucky enough to grow up in the city of Kalamata, where the catastrophic earthquake of 1986 worked as an incentive for the local government to strongly support arts and culture in order to regenerate the city. As far music was concerned, this led to the establishment of a model Municipal Conservatory, where from a very early age we had the good fortune to come into contact with some of the most important figures in music at the time, including Nelli Semitekolo, Eleni Zacharaki, Manos Avarakis, George Kouroupos, Kostas Nikoleas, Nikos Tsotras, Stefanos Vassiliadis and Grigoris Semitekolo among many others. Guided by this creative environment that was so generously open to us, simply and effortlessly, and with such open-mindedness, we as students embarked on a whole new journey. The artistic bar was set very high; just imagine studying History of Music at the age of 10 with musicologist Katy Romanou, to mention just one example. For all of us who studied there, that ideal situation is something we always carry with us.

My transition from piano and classical percussion to the kanun was part of a kind of fearlessness that you acquire in this kind of environment. The kanun came just before my piano degree and it was like love at first sight. I left everything without a second thought, and since then I go wherever it takes me, at any cost. What happened before this encounter with the kanun is in effect my dowry in musical training: piano and classical percussion, orchestral experience, classical and contemporary repertoire; serious study; sound and phrasing; meetings and seminars with musicians from very different backgrounds. When the kanun appeared in my life I did not know what music it represented, but I was fascinated by its sound and saw it exclusively as an instrument with infinite possibilities, that I can do with it whatever I want. Luckily, I soon realized that in order to really be able to do what I want, I would first have to learn the music that it represents. So I graduated with a degree in Byzantine Music studying under the instruction of Spyros Pavlakis at the National Conservatory and while I had a lot of work as a session musician, I gave up everything once again and left for Istanbul to focus on what I loved most.

Your latest album “Sisyphus” won many accolades – including a place in the best ten records of 2021 at World Music Charts Europe. Does the label “world” or “global” music cover you? What do you think it represents now?

Indeed, the record is going surprisingly well and I am incredibly grateful for that. I think the label “world music” is an umbrella term that encompasses a lot of concepts and genres today. Inevitably I find myself somewhere there, mainly because of the origin of the instrument. As a reflex response, however, I insist on not belonging anywhere specific and on reserving my right to change and experiment as much as I can. I adopt what sparks my interest and try to incorporate it into my already existing material. I prefer not to hide behind the security of a label, no matter how wide it is. I do a lot of different things and probably each of them could belong to a different category. But in everything I am myself and I do not care at all what it is classified as, or how much people will like it. It is enough for me to like it in the first phase.

Now, what does “world” or “global” music mean today, in a world where technology can transport you in seconds -in the virtual world- or in a matter of hours -in the physical world- to whatever information or place in the world you want? Infinite access to information I think is the key concept. The way each of us handles this situation and how much we delve into what moves us is always very personal. The truth is that everything is, or at least appears to be, within reach.

Tell us about your music. Your influences are varied, including Ottoman music, Greek folk music and classical music. How do you combine these different sources of inspiration?

I try to make the music I would like to listen to, and because I am ruthless with myself, nothing is done easily or carelessly. Anything that gets published has gone though harsh criticism and has traveled an entire journey within me. Not to mention the fact that by the time a piece of my music gets published, I have already managed to distance myself from it. If something does not pass the test of time, it does not come out. Not so much out of insecurity, but more out of a sense responsibility. I also love poetry dearly and I admire poets very much. Whenever there are lyrics, the weight shifts there; they come before the music. Moreover, because I very rarely write songs, when I decide to do so, I do it with the utmost respect so that not even a comma will go unchecked. I will dig into it and go in as deep as I can handle.

Beyond classical and modern music with which, as I’ve said, I came in contact from a very young age, the kanun led me to musical roads and worlds that I could not have imagined. Byzantine music and the folk idioms of the Greek and Greek-speaking music world are obviously my primary materials. Ottoman music and makam theory are perhaps the most important areas of study when it comes to Eastern musical instruments. Eastern Mediterranean folk music, medieval music, traditional and free improvisation are things I love and have worked on a lot. All of that in some way makes up my musical personality.

Sometimes my relationship with a musical idiom begins from a personal quest, while at other times from collaborations with people who came from other traditions or represent other musical genres and idioms. Some of my most important collaborations have been with John Psathas, Mamak Khadem, Marta Sebestyen, Efrén López, Lost Bodies, Robyn Schulkowski, Dominique Vellard, Yannis Saxonis, Guitar Kanun Duet, Vassilis Ketentzoglou, Eleni Christou, Kalman Balogh, Xavier Charles, Tijana Stankovic, Ballake Sissoko, Ourania Lambropoulou and Orestis Karamanlis, to name a few.

What is the thread that connects Albert Camus’ myth of Sisyphus with Kostis Palamas’ poem O Gremistis [The Demolisher], the two main literary references of your album?

I defer to the triptych Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis in my own very personal and chaotic way. All the shapes that represent a circular or spiral path to infinity fascinate me. This is how “O Gremistis” is connected with Sisyphus; through the historical continuity of the concept of the Hero. Disobedience is also a driving force in both cases, as well as the questioning of both oneself and of an outdated perception of concepts such as order and security. Sisyphus and Gremistis are both adventure seekers [tyxodioktes]. A word I also really like. But the question here is: Why does this word acquire a negative meaning, so incompatible with its [Greek] etymology?

Palamas’ imperative to “Demolish!” is in perfect harmony with Camus’ Sisyphus’ smirk during his fall. Behind both actions lurks immense joy and relief, as well as this feeling of being driven by a higher purpose, while at the same time being far removed from the notions of polite society, where to fall means to fail. For Sisyphus and the Demolisher, this is just the beginning of a creative journey full of knowledge, experience, awe, courage and freedom from any barriers. The purpose is to go back to basics. To zero. Lest we forget; everything is open and the future is uncertain. Everything is in the here and now.

We live in a time in history where we are mostly surrounded by swampy peaks and lowly leads. By people who are hooked to these top positions and do not let things run smoothly; people with no imagination or vision, who insist on “squaring the circle”. We witness the results on a daily basis: wars, poverty, injustice, inequality. Both “Gremistis” and Sisyphus have a very strong sense of justice, leading by example and paving new paths no matter the cost. They do not take anything for granted; they understand that the real way up is when you do not lose your connection with earth and memory -whatever that is for each and everyone of us.