Sotiris Sorogas is one of the most prominent figures in Greek painting. Throughout his long artistic trajectory, he has developed a unique visual language. His subject matter transcends not only its representation but also space and time. It ultimately becomes a symbol raising existential issues, alluding to life, death, decay, and the inevitable.

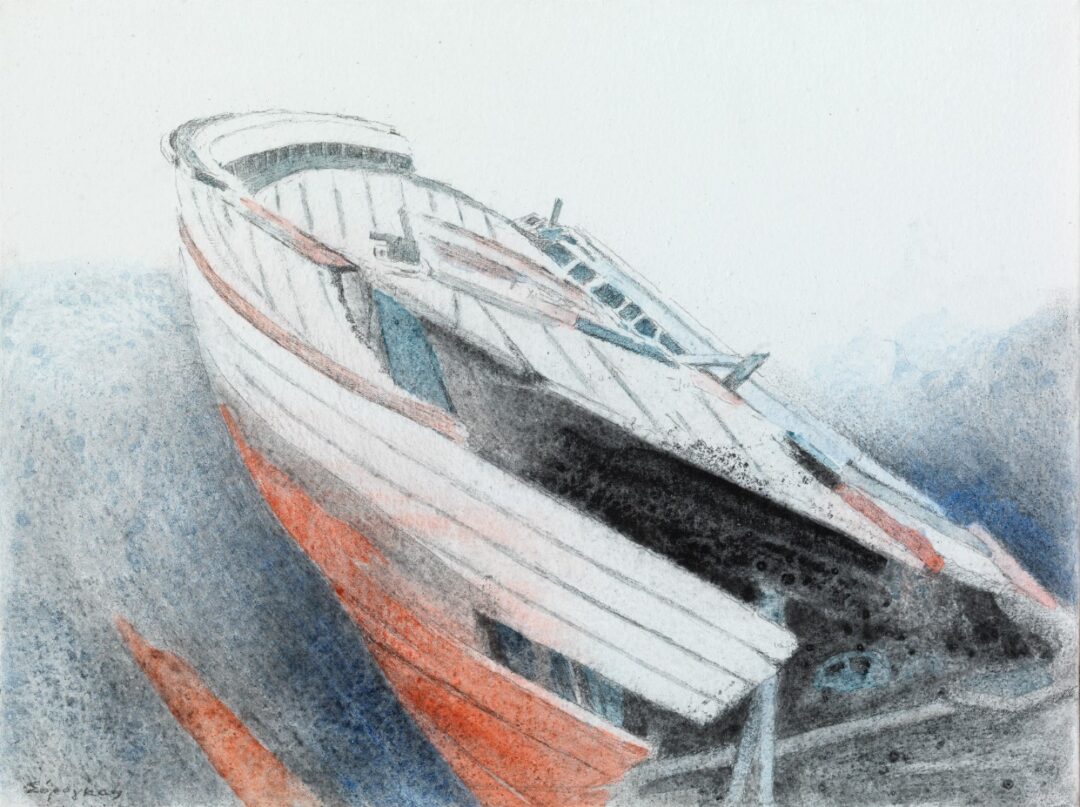

His art assumes a metaphysical, spiritual dimension encapsulating the very essence of things. Worn, rusty objects, old boats, wells and random pieces of wood invite the viewer to reflect on the ephemeral. Rugged subjects are depicted with lyricism leaving us wondering about loss, memory, and rebirth. Perishable objects are defined by a sublime aesthetic quality.

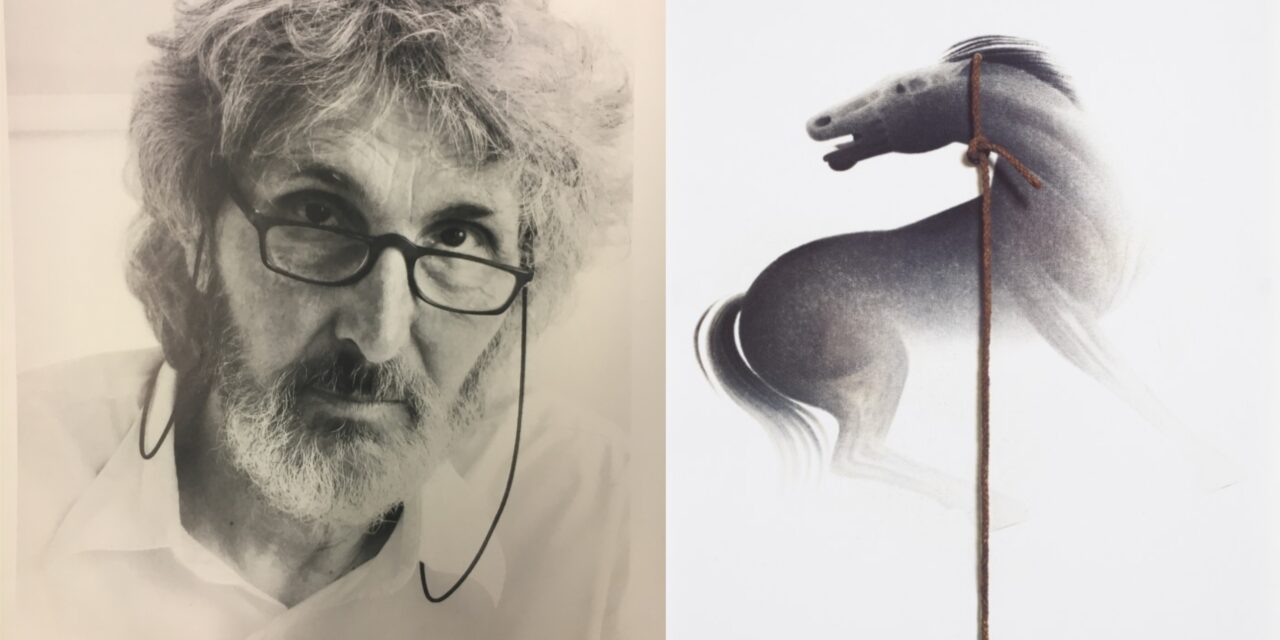

Sotiris Sorogas is a calm, gentle man deeply dedicated to his art. He has a poetic way of approaching things. His intellect and artistic honesty are expressed in a nostalgic manner through his art.

He was born in Athens in 1936. He studied with a state scholarship at the Athens School of Fine Arts, where he graduated in 1961. In 1972 he received an annual personal grant from the Ford Foundation. He has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in Greece and at international events organized by the Ministry of Culture, the National Gallery, and private art galleries (Tokyo, Brussels, Dublin, Sao Paulo, New York, Paris, Rome, Basel, etc.).

He taught drawing at the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens from 1964 to 2003. Today he is professor emeritus.

In 2004 he was awarded by the Academy of Athens for his entire artistic contribution and in 2019 the President of the Hellenic Republic awarded him the Order of the Commander of Honor.

Sotiris Sorogas spoke to Greek News Agenda * about art, time and poetry.

What does art mean to you? Is it an internal, solitary process or is it conceived in reference to the public?

Over the years, there has been an infinite number of answers regarding the definition of art. This is due to the wide range of its meanings. I would say that your question encapsulates what art means to me.

It is definitely an inner, solitary, process that seeks recipients. In fact, I believe that this is the intrinsic element of its existence.

As far as I am concerned, it also functions as a silent confession and therefore as a redemptive dialogue with the people to whom I am trying to convey the mysterious miracle that constitutes everything that surrounds us.

Icon painters were the first to teach us the sanctity of their work. The monk, icon painter, and author of Interpretation of Painting Art, Dionysius of Fourna in Agrafa, recommended that the monks, before attempting to depict the icon, should fast and pray to the Virgin Mary.

When did you realize that the art of painting is what you want to do, that it is what you love and want to serve?

I must have had an inclination for artistic activities from a very young age. I loved carving boats out of pine bark, drawing Christmas cards and playing the harmonica.

At the age of 12-13, because of a thyroid disease, I was already 2 meters tall. That was the time that my drawing ability became a refuge and, to a certain extent, a way of redemption from the surrounding brutality of the scorn and ridicule that I was subjected to by almost everyone, except for those close to me.

In the end, painting as well as constant reading would contribute to alleviating my misery at that time. By painting, I could depart to another world, of another quality and another ethos. I believe it was the gift of a Divine Providence that reached me from unknown paths and inscrutable starting points. It seems that art is indeed the breath of the lonesome and as Dimoula puts it in her unique way: art “was appointed competent to issue certificates of pending existence, because it has the gift of suffering”.

Which were your initial influences and how did they evolve along the way? Could you integrate your style into a particular artistic genre?

While I was studying influences did not exist. I had to learn the language of painting first. I was lucky to have as a teacher Yannis Moralis who was ideal. We were all convinced of its necessity and its valuable contribution to our efforts. We were learning in the midst of complete freedom, so each of us went our own way. Preferences and affinities came later. Van Gogh, however, was a saint for all of us. My work was classified by several critics as “in poetic realism” one of the many “Schools” of that time. If my painting is good, it can lay claim to something of “surrealism” where Engonopoulos classified all worthy art.

How do you choose your subject matter? Describe, as far as possible, the creative process you follow.

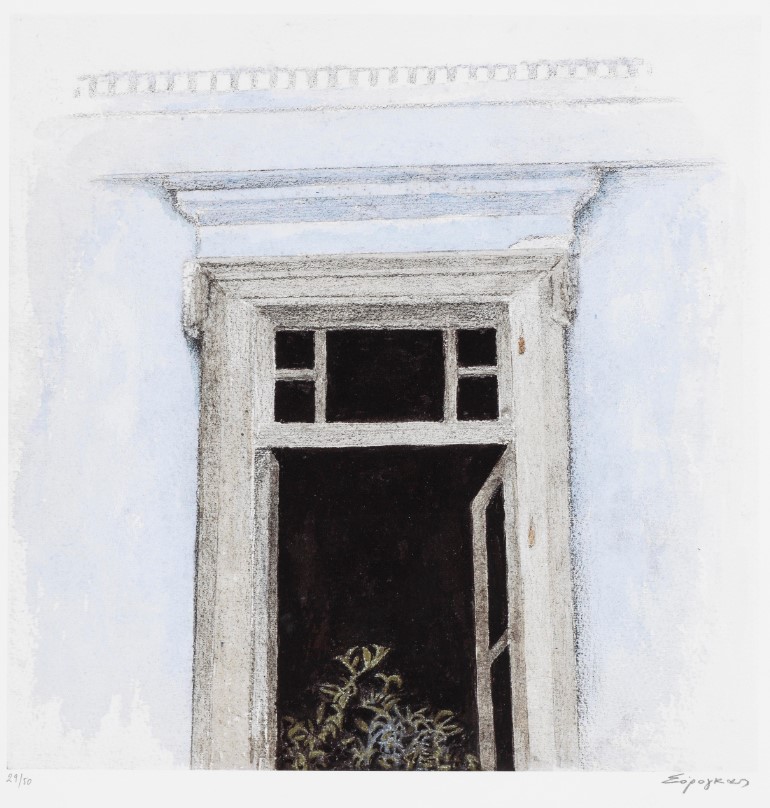

The choice of subjects depends on the orientation, particularities, and preferences of the painter. Many paint almost exclusively people and others implicitly indicate their presence. For example, a half-open door may indicate their passing. The variety of versions and themes is endless. My preference is for things that are about to disappear. Rusty sheet metal on stones, old stopped machinery in deserted quarries, old wood from demolished houses, dilapidated boats, old wells and dry stones of deserted fields. Sometimes I put a small flower at their roots to remind me of spring.

What was that moment in your career when you felt you made your mark in the art world?

I think only an arrogant person would think that they can make their mark in the art world. In any case, this would have to be affirmed by others and time.

How do works of art converse with time? Which are those that ultimately transcend it?

I think none of us know which artworks will transcend time. The constant changes in people’s lives also modify aesthetic orientations and often take with them the works that were cherished in their time. Seferis, in his monumental text “Monologue on Poetry”, claims that poets like Pindar can be ignored for centuries and even scorned. Every era, I believe, finds itself in its own art.

What is your own relationship with time, as a human being and as an artist?

I have come to the conclusion that my profound and lasting love for poets and poetry is because I find in them, among other things, my own obsession: Time. I quote what Κiki Dimoula, whom I’ve been rereading lately, read upon entering the Academy: “Time. Long…. If one thinks about it, life is a tireless enthusiastic applause to everything that saws it, to everything that wears it down”. Nikos Karouzos looking at a rose writes: “What a horror, the seconds eat it up.”

You have occasionally expressed your concern about the commercialization of art. How does the system of promoting the artistically insignificant, sometimes blatant, work of ‘art’ ultimately work?

Answering this question would require at least a PhD thesis. It is true that in the past, I have occasionally referred to the commercialization of art. It has now been assimilated by the dominant mechanism that has already incorporated everything into it. Man, nature and every aspect of our life. There are of course resistances and individual activities, but they are in vain. They are reminiscent of poor farmers, plowing their little fields by themselves. Today painting is absent in art museums. They are filled with objects invented by arbitrary signifiers and explanatory texts that inform the visitor of the significance of the object. They call them “Installations.”

Is there a criterion that irrevocably defines which work is really of high artistic value? What are the characteristics it must have and who is the final judge?

None of the above is possible. It is impossible to have such a criterion that defines artistic merit for art.

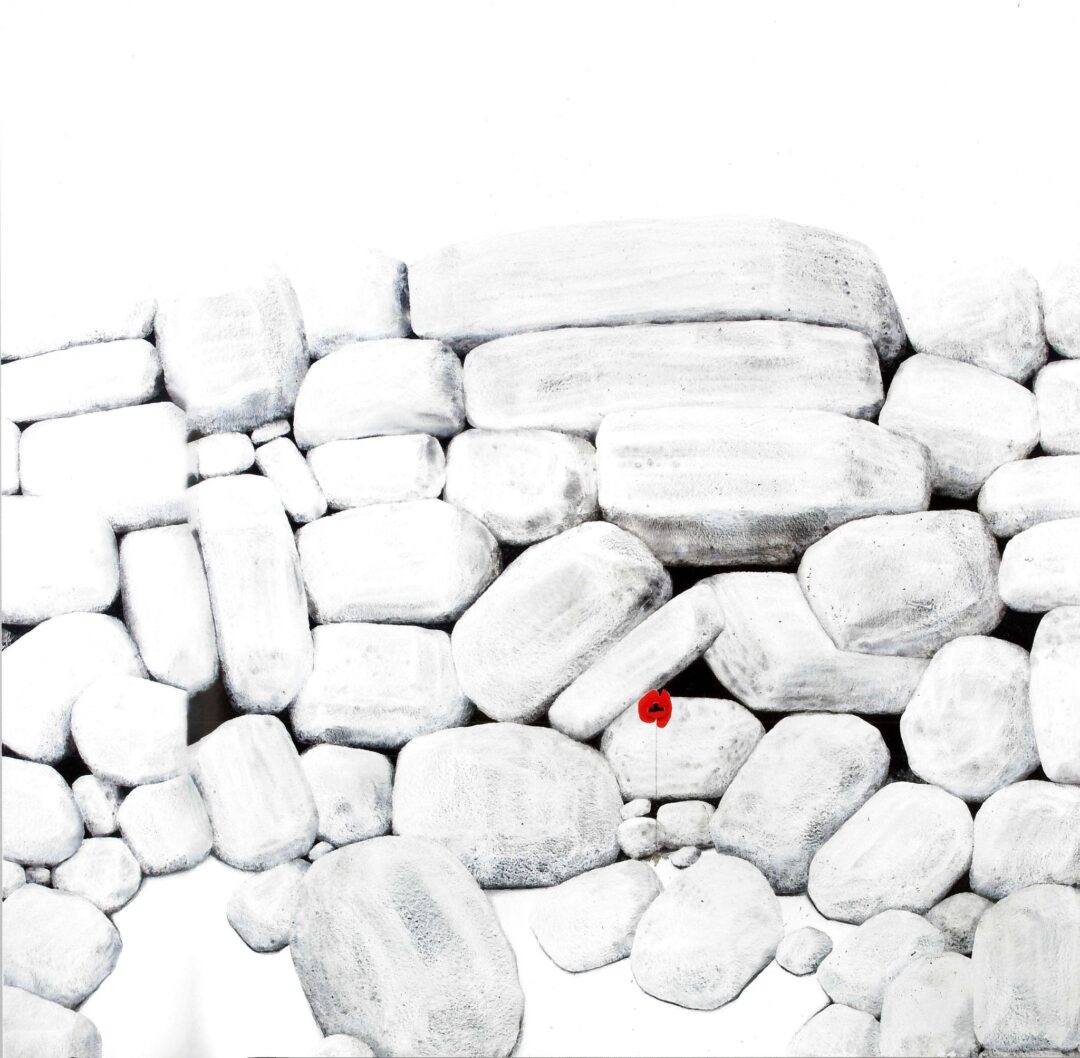

Stones and poppy is a cherished painting. Tell us its history, the circumstance in which it was created and what does it mean to you?

During the period of the dictatorship, the feeling of absolute lack of freedom in the gloomy atmosphere of those days, I was concerned about how painting, through its inherent silence, could express a clear message, such as Delacroix’s The Massacre at Chios.

Among my attempts, Horse with a Rope or Blood under the Statue, I painted a poppy near the stones as an announcement of a spring that would definitely come, since it is an inalienable law. It was printed in a lithograph of 75 copies. In ten days it was sold out.

Everyone loved it. I don’t know if that was resistance. I don’t believe in politicized painting, because even if it succeeds, the purpose of the message will be one-dimensional. I believe that good painting, in addition to its message, creates a feeling or rather an emotion that emerges from the depths of the subconscious, which is why it remains undefined. In an essay on Picasso, I wrote something about art that I still believe “Great art listens to the inarticulate word that vibrates the silence of the world.”

*Interview by Dora Trogadi (Intro image: Left: Sotiris Sorogas; right: Horse with rope, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 1985, private collection)

Read also via Greek news Agenda: Arts in Greece | Sotiris Sorogas’ Poetic Approach to Time and Memory; George Rorris: “A painting is the sincere revelation of one’s soul”; Kostis Georgiou: “Art’s purpose is to provide a zone of unlimited paths”

TAGS: ARTS | EXHIBITIONS | PAINTING