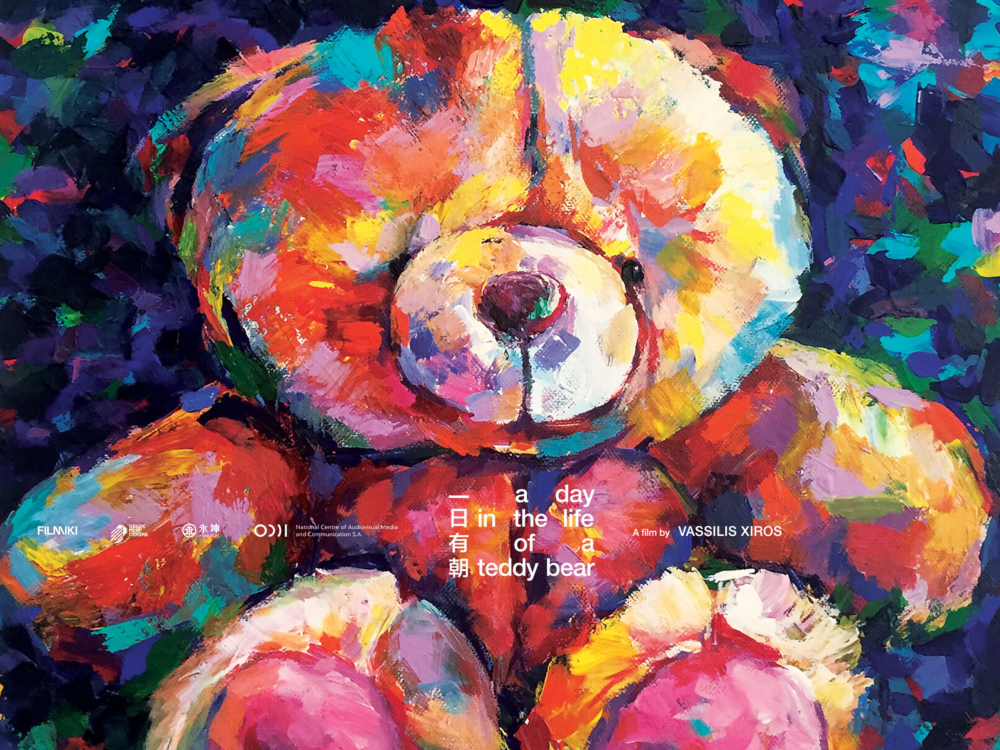

A Day in the Life of a Teddy Bear is the first feature film co-produced by Greece and China. It follows Liu Jinxi, a Chinese violin player, and Panos, a Greek architect; after their chance meeting, brought on by a discarded teddy bear, they embark on a long walk in the city of Shanghai – and a budding love story.

The film, filmed in Shanghai, Vienna and Lefkada and starring Chinese actress Tu Hua and Greek actor Dimitris Mothonaios, was written and directed by Vassilis Xiros, a Greek Diplomat who served as Consul General of Greece in Shanghai in 2015-19. Its Greek title is A Day in Shanghai, and the director’s intimate knowledge of, and love for, the Chinese metropolis are obvious, whether he shows splendid panoramic views or small corners of the city.

Vassilis Xiros with actress Tu Hua

Vassilis Xiros with actress Tu Hua

Vassilis Xiros, who makes here his directorial debut, is a career diplomat who has always had a strong artistic side, as he also plays and composes music, and writes fiction – his first novel was published by Kedros in 2019.

His interest in the arts has also influenced his work as a diplomat, as he had already placed emphasis on the use of cultural exchange as deputy head of the mission for the Greek Embassy in Seoul; following his time in Shanhai, he became a member of the team that prepared the events for the “China-Greece Year of Culture and Tourism 2021“, serving as diplomatic advisor to the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.

On the occasion of the film’s release in theatres in Greece, Greek News Agenda interviewed* Xiros on combining a diplomatic career with film directing, the challenges faced by an independent filmmaker and the way culture can bring people together.

From being a diplomat to being a filmmaker. How can you describe the distance between the two?

From being a diplomat to being a filmmaker. How can you describe the distance between the two?

Both capacities require a strong set of negotiation skills, especially when being a producer as well, as it was the case with me and my film. You also need tenacity, courage, adaptability… I suppose the main difference is the level of sincerity: contrary to common perception, a diplomat ought to never lie, but on the other hand, he usually presents an embellished version of reality, whereas a director has to dig for the truth and bare his soul.

Which part of making the film did you find most challenging?

Raising the budget and putting it to best use is probably the hardest part of any film – considering that strong ideas and talent are there of course. Again, a common perception for the work of a director is that he is mainly responsible for designing the shots, but this is just a small part of it. Most film projects don’t even reach production stage, but even when they do and you already have a cast, a crew and a budget, you have secured or set up a location, designed the blocking (actors’ movement) and rehearsed a scene, finding an interesting camera angle is usually the least of your troubles. A great part of the director’s work is also done during post-production.

It all sounds very time-consuming. How easy was it to combine it with your diplomatic job?

It all sounds very time-consuming. How easy was it to combine it with your diplomatic job?

Apparently, it required lots of passion and energy, as well as dedicating all of my free time outside work to the film – at least all the free time left aside from the diplomatic social functions. During pre-production and post-production, time management was more flexible. During the shooting, which for the Shanghai part lasted for a couple of weeks, I had just finished my term as a Consul General, so I could dedicate all of my time to it. By then, I had already moved from my house and was staying in a hotel, along with the rest of the crew.

Do you consider the city of Shanghai to be one of the “characters” of your film?

Yes, without Shanghai this would have been a very different film altogether. Of course, I’m focusing to certain sides of the city that I found most appealing, in particular old Shanghai. I always found it fascinating how a city of 27 million people can have an atmosphere of serenity and humanity. The organisation and safety of the city is a great achievement of the local authorities. The element of water is also very strong in the city, as well in the movie. Shanghai has lots of creeks and canals and is surrounded by the so-called water-towns. Shanghai has been changing very fast over the past few years, modernising itself at a fast pace and a certain cost, so I hope the movie also serves as a reminder of what the true soul of Shanghai is.

Do you think culture is an effective means of bringing two peoples together, and in particular Greece and China?

Do you think culture is an effective means of bringing two peoples together, and in particular Greece and China?

Yes, building more cultural ties between the two countries had been a priority for me ever since I assumed my duties as a Consul General. More so since I understood that, despite the economic rapprochement of recent years, there was still a big gap of cultural perception in both countries, particularly with regard to modern culture. I’m referring to culture in the broader sense, including elements of our daily lives. China’s importance is too big to remain relatively unknown in Greece. I’m satisfied that viewers come out of the film with a different perception of China than the one they had before.

Is there still a space for independent filmmakers and movies in our days?

I’m not sure if I’d recommend to anyone to do what I did. There is apparently a huge cost to it, in every possible way, particularly without a strong studio support. But if you can communicate with someone through the movie and leave a long-lasting impression on them, then, I suppose, every sacrifice is worth it. Unfortunately, auter cinema is in decline, as are cinemas in general in the post-Covid era. I hope there is still a chance that movie theatres will bounce back and claim their share from platforms.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Yorgos Goussis explores the power of togetherness in “Magnetic Fields”; China’s image in Greece: Great Expectations

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Yorgos Goussis explores the power of togetherness in “Magnetic Fields”; China’s image in Greece: Great Expectations