The Asia Minor Catastrophe (which caused an influx of Greek refugees from Turkey to Greece, following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922) is a historical event that defined Greece’s economic, political and social reality. In the arts field, two major changes are observed. First, landscape painting gives way to a more anthropocentric approach and, second, the concept of “Greekness” in Greek arts emerges, as this tragic event is deeply related to the idea of cultural identity. In that sense, many artists return to ancient Greek art and the Byzantine and folk traditions, as pillars of the Greek cultural identity.

During the Interwar period, a shift from the radical avant-garde movements of the first 20 years of the century to the so-called “return to order” sparked a new interest in tradition. The rise of authoritarian regimes undoubtedly favored this approach, which served their strategic and ideological goals. However, this new approach is unfolding in close relation with European modernism.

The 20th century heralded new artistic pursuits. At that time, there was a shift towards an approach in arts and literature that denounced the ‘provincialism’ of intellectual life, the ‘attachment to the past’ and the ‘ignorance of the present’ that prevented Greek artists from producing works of ‘European importance’, as pointed out by G. Theotokas in his essay, “The Free Spirit”, published in 1929 – the intellectuals’ manifesto. The need for change is obvious but has not taken shape yet. As Marina Lambraki Plaka points out, in the field of arts, artists “are tired of Munich but Paris frightens them”. The purity of Greek light cannot be depicted by applying the principles of Impressionism.

Except for the heretical case of F. Kontoglou, who ostentatiously turns his back on modern art to focus on the utopia of the revival of the Byzantine tradition, all the other “Greek-centric” artists are, at the same time, profoundly modern. They look to tradition for patterns and lessons to reinforce their modernist quest.

What brings together the artists of this period is a straightforward reaction towards academicism. They aspire to align with Greek ideas on one hand and avant-garde European movements on the other. Modern art and tradition function as catalysts for this generation. Tradition is now reinvented in a way that expresses modernism.

Artists looked to tradition for values. They rediscovered the symbolic world of Byzantine painting, the decorativeness of folk art, the geometric texture of its forms and the harmony and balance of classical art. Tradition is seen as the way to create an authentic new approach to arts.

Painters standing for liberal values and ideas seem to align with the liberal ideas of the political spectrum and vice versa. Conservative artists belonged to the “Association of Greek Artists” headed by Georgios Iakovidis while more liberal ones to the “Art Group”. This debate between the academic establishment and the progressive ideas that aspire to revitalize art unfolded in tandem with the political and social life of Greece.

The 1920s are a transitional period. The progressive painters of the previous decade are now the protagonists of the arts scene in Greece and are fully supported by liberal governments. Parthenis, for example, worked closely with the Venizelos government and in 1920 his emblematic retrospective featuring 240 paintings was exhibited at Zappeion Megaro.

The idea of purely Greek art had already been put forth by Periklis Giannopoulos in 1904 and the first Greek modernist landscape painting emerged in the 1920s. The Asia Minor Catastrophe, though, was a catalyst towards the direction of a purely Greek art, estranged from foreign influences. The dictatorship imposed by Metaxas in 1936 continues to support modernist artists through extensive assignments for public spaces, for example the Athens Town Hall by Kontoglou and Gounaropoulos.

There was no reason not to support modernism highlighting Hellenic characteristics since all totalitarian regimes in Europe favored similar tendencies. The Generation of the Thirties in the field of arts consists of a group of people who are well-informed, conscious of the goals they want to attain, open to challenges, and extroverted.

This is a time of great cultural significance, characterized by the emergence of artistic movements that redefined the boundaries of Greek art. A new generation of artists emerges for the first time, with the support of progressive governments that gives rise to the so-called “Generation of the Thirties”.

Greek artists, authors, and intellectuals share their concerns through important publications; «20th Century” published by Tombros in 1933, the Third Eye magazine published by Stratis Doukas, Pikionis, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, Spyros Papaloukas and Sokratis Karantinos in 1935 and the newspaper Techni in 1938. As modernism emerges there is a need for theoretical debate and these publications served this purpose expressing the artists’ need to enhance their horizons and share their intellectual quests. It is no coincidence that the first issue of the newspaper Techni featured Tsarouchi’s essay on Theophilos, one of the artists that deeply influenced the Generation of the Thirties.

Under the influence of Pericles Giannopoulos’ “Hellenic Line”, which laid the foundations for aesthetics, τhe emphasis was placed on Greek light’s spiritual quality and intangible character along with the reinvented folk art. Tradition and modernism act now as powerful catalysts. This double reference presented no contradiction for the Generation of the Thirties. On the contrary, it was the necessary component for the authenticity of modern Greek art. Whatever was Greek, Byzantine, and folk was at the same time modern.

Theophilos Ηatzimichael (1873-1934) was arguably the most important figure in Greek folk art. His colorful paintings bring together religious themes, gods, heroes and everyday people. His figures are depicted in a rather simplistic manner, creating a world of innocence and authenticity. His recognition is largely owed to the famous art critic Teriade (Stratis Eleftheriadis).

Fotis Kontoglou (1896-1965) was one of the most prominent advocates of the ‘return to the roots’. He was a firm supporter of tradition and authenticity in Greek arts and as a painter he drew inspiration from Byzantine and folk painting. His works deeply influenced modern Greek ecclesiastical painting.

Konstantinos Parthenis (1879-1967) was inspired by Byzantium, symbolism, and cubism. His art stands out for the purity of the Greek light. His spiritual allegories and idealistic visions create a world where Antiquity meets Byzantium.

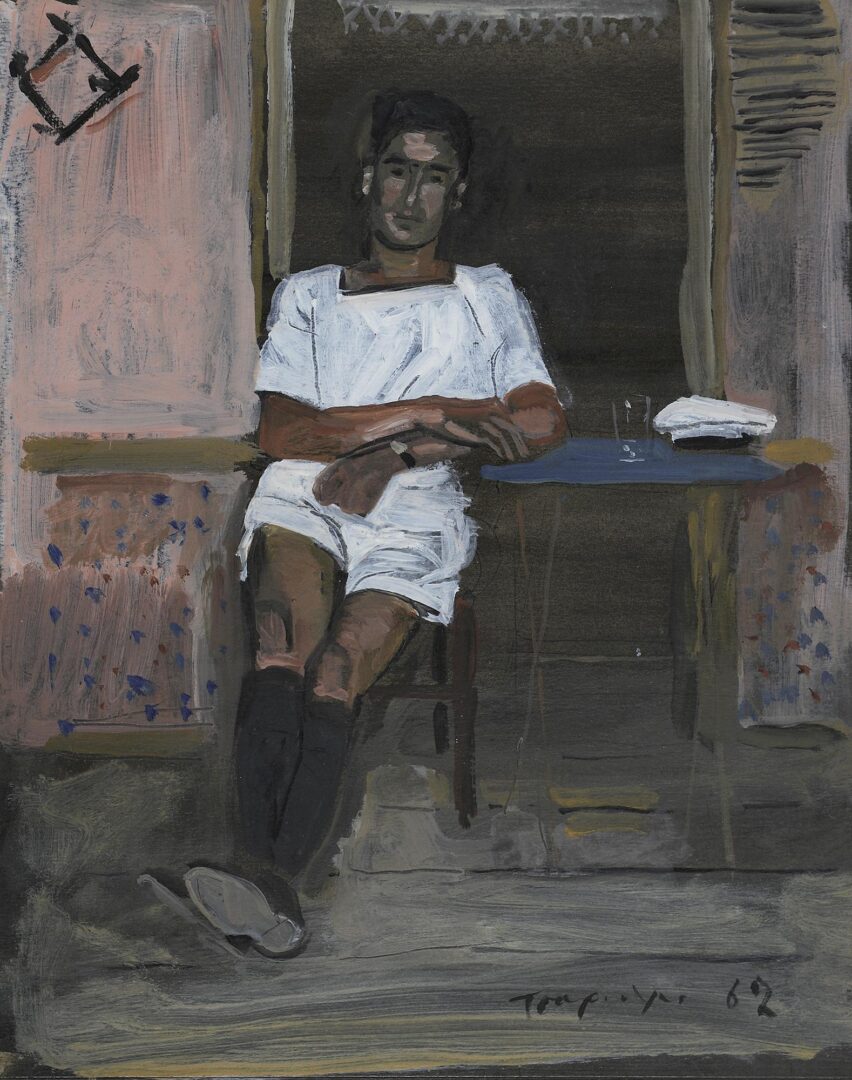

Yannis Tsarouchis (1910-1989) is probably the most popular representative of the “Thirties Generation”. He draws inspiration from Hellenistic, Byzantine and folk art, Fayum, and a wide range of artists such as Kontoglou, Theophilοs and Matisse. His art eliminates the antinomy between old and new, foreign and Greek. The idea of “Greekness” is highlighted in his art. He mainly focused in depicting human figures (nudes, portraits, scenes with sailors and soldiers) as well as landscapes, still lifes, nudes and allegorical scenes.

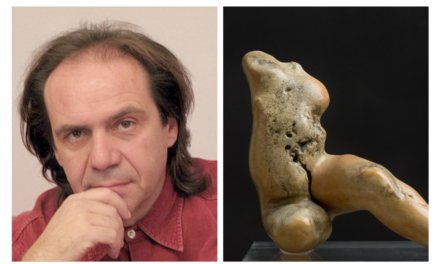

Nikos Engonopoulos (1907-1985) was one of the greatest intellectuals in post-war Greece and one of the leading figures of surrealism. Strongly influenced by his teachers, Parthenis and Kontoglou, poet Andreas Empeirikos and Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical painting, Engonopoulos creates a world where Byzantine elements coexist with surrealist ancient armors, fustanellas and crinolines. His art unconventionally incorporates, Greek folk tradition, mythology, antiquity, and Byzantium. At the same time, it is defined by ironic, erotic and humorous elements. The symbols he uses are not just elements of the individual subconscious in the way the interwar surrealists used them, but mainly symbols of history and civilizations of ancient times.

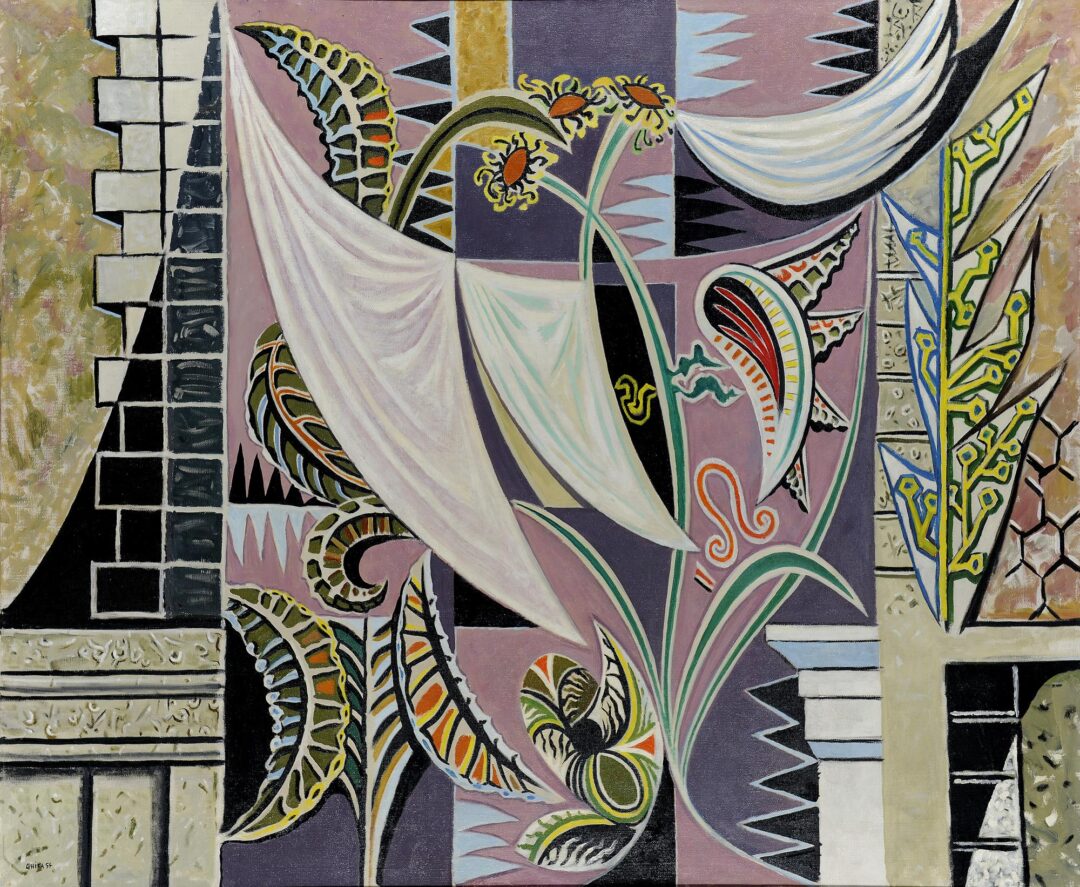

Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas (1906-1994) was a prominent figure of the renowned “Thirties Generation” in Greece and the most important representative of cubism in Greece. He studied under Parthenis (1921-1922) and at the age of 16 moved to Paris where he studied French and Greek literature while developing his artistic endeavors until 1934. He soon developed his unique visual idiom. After his return from Paris, he collaborated with architect Pikionis, painter Papaloukas, author Stratis Doukas in the review The Third Eye (1936-1937).

His compositions reflect his dialogue with great modernist artists (Picasso, Braque, Derain, Matisse) mainly through geometric abstraction and post-cubism. Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas ‘hellenized’ Cubism, transforming this intellectual expression into a painting of the countryside. His paintings exemplify the clarity and sublimity of the Greek light, which is different from the one encountered in other countries that contain grey and shadows. “In Greek art, there is no chiaroscuro”, he argues. His art highlights the mountainous and rocky character of Greek nature, and the dryness of the landscape that is depicted through geometric patterns.

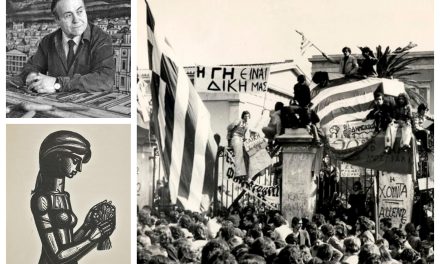

Georgios Gounaropoulos (1889-1977), was also one of the painters that sought to break the academic tradition in Greek painting. Inspired by impressionism he created his surrealistic style expressed through linear female figures and compositions imbued with a dreamy and lyrical atmosphere, where the game of light and shadow play a leading role. His art is imbued with a lyrical and dreamy atmosphere, where the game of light and shadow plays the primary role.

Gounaropoulos studied painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts (1907-1912) under professors Spyros Vikatos, Dimitrios Geraniotis, Georgios Roilos and Georgios Jakovides. In 1919 he went to Paris where he completed his studies at the Julian and Grande Chaumiere Academies. During his stay in the French capital, he took part in Parisian Salons and in 1926 presented his first solo show at the Gallery Vavin-Raspail. He permanently returned to Greece in 1931. In 1958, representing Greece, he received the international Guggenheim Prize and in 1975 his work was presented in a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery.

His artistic creations include illustrations of poetry collections and wall paintings for the meeting room of the Municipal Council of the Mayor’s Office of Athens, which featured scenes inspired by mythology and the city’s history (1937-1939).

Dora Trogadi (Intro Photo: Reflections Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas)

Read also in Greek News Agenda: Theophilos, the genuine Greek folk artist; Fotis Kontoglou, The Greatest Icon-Painter of Modern Greece; Konstantinos Parthenis: The “Poet’ of Modern Greek Art; “I was and I remained a scholar and a student“ at the Yannis Tsarouchis Foundation; A Journey Through the Surreal World of Nikos Engonopoulos; A digital journey into the world of Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas

TAGS: ARTS