Sozos Yiannoudes (Cyprus, 1946) is a graduate of the School of Fine Arts. From 1972-2004 he taught fresco painting and portable icons technique in the Athens School of fine Art. In 2004 the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew honored him with the title of Grand Master for the 10 years of missionary service in Korea. He has worked in Greece, Cyprus, Korea and England. In his interview with Greek News Agenda* he talks about his experience as an iconography teacher in Korea. The initiative of these workshops was taken by His Eminence the Most Reverend Metropolitan Ambrose (Zographos) of Korea who,in addition to his service, is also full professor at the newly established Department of Greek Studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in South Korea.

How did you decide to come to teach iconography in Korea?

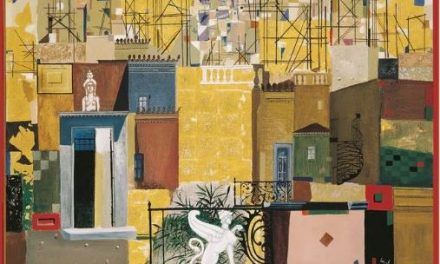

It was in 1994 when former Metropolitan of Korea, and current Metropolitan of Pisidia (Turkey), Mr. Sotirios Trambas, invited me to paint the Metropolis of St. Nicholas in Seoul. I always wanted to go on a mission trip and so I accepted his invitation. Since then I have painted around ten churches in all of South Korea.For the implementation of this difficult project, I worked with a team of students from the Athens and Thessaloniki Schools of Fine Arts, various other collaborators and my children. We all worked on a volunteer basis.His Eminence the Metropolitan, strangled to find sponsors both in Greece and abroad to cover our travel and subsistence expenses. In exchange, we decorated the churches that the Metropolitan had so painstakingly built during the previous years. When the economic crisis hit Greece, sponsorships came to an abrupt halt. As a result, iconography in Korean churches stopped for a long period. Two years ago, I received a request from both the former and the new Metropolitan of Korea, Mr. Ambrose Zographos, to organize a one-month byzantine iconography workshop in Korea. We are now on our third year and the interest is great.

What is your impression of the Korean Orthodox community?

My experience from the Orthodox Community in South Korea has profoundly marked my life. The community has currently 6500 to 7000 adherents, many of whom used to be atheist, areligious, Buddhist, Protestants or belonged to other religions. Their love for our Orthodox Church has impressed me very much. There are worshipers who travel up to four hours just to come to the Sunday mass. They sing with devotion, they know the service, the psalms and the order of the canons. The majority has received formal music education and they contribute to the service in an effortless manner. Sometimes I feel awkwardly when I realise that they know so much more than I do. They love their community that revolves around the church, which they consider their refuge. The decisions are always taken collectively. They discuss things and together they reach a decision. When I first went to work there, they told me what kind of religious paintings they wanted me to paint. I had to follow the byzantine style of course, but, at the same time, take into account their tradition, their customs and their experiences. For instance, they feel fear when the eyes of the Saints look at them straight in the eye or when the scences are too densely painted. They also do not like colours when they are too bright. I respected all that. I also give my own intepretations. One would be that in the entrance of the Buddhist temples, there are the so called “protectors of the temple”, four figures on the right and left of the entrance with fierce looking faces and protruded eyes. Also, the Buddhist temples are very densely painted with very bright colours. It is possible that the Orthodox Community does not want its churches to look like Buddhist temples.

What is the profile of your Korean students? What do they seem to appreciate the most in byzantine art?

The people who take part in the workshop belong to different religions and are eager to learn more about the interpretation and the symbolism of each icon. Many are Fine Arts graduates so they already know how to draw and how to use color and composition. Thus, they are able to quickly determine the subject-matter. Nevertheless, through the workshops they try to approach the symbolism, the style and the expression of the Byzantine icon and to appreciate its transcedental and rich content. My students are mostly Koreans. They are diligent, organised, meticulous, kind and they appoach what they do with great respect and love. Their love for the environment and nature is also remarkable. At this point, I would like to take the opportunity and talk about something that impressed me a lot. After the war, both South and North Korea were completely burned by Napalm bombs. Once a year, everything used to be closed by law so that the citizens could go and plant trees. This law was abolished almost twenty years ago but by now the country has been fully replanted from one end to the other. I wish our beautiful country would follow the example of Korea. I try to do so by planting trees inside and outside my house even though I have received not only positive but also negative comments about it.

What deeply impacts my students as they immerse themselves in the expressive richness of the icon, is the diversity and the explanation behind each brushstroke that is charged with symbolism. Once they understand the icon, my students get to love it so much that I feel they take something away from my own immense love for it. In order to appreciate the byzantine icon, they need to understand its philosophic interpretation: the illustration of any natural or perishable element is to be avoided; the illustration of a sainctified, transcedental face is very different from a common portrait or photograph; the rule of the two dimensional illustration with the abolition of dephth and perspective; the beauty of the illustrated face which is understood once we analyse the proportions and the inclination of the face (always in three-quarter view). Finally, the rich colour palette that is used for the dresses as well as the way a woolen dress is differenciated from a silk one are some of the various elements that highlight the unique artistic expression of the byzantine icon and raise many questions with my students.

Have the workshops inspired your students to learn more about Greece and the Greek culture?

Koreans know a lot about Greek civilisation and culture and want to come to Greece to see for themselves all the things they have read about or learned during the workshop. For instance, they are familiar with Manuel Panselinos, Theophanes the Cretan and Theophanes the Greek, the teacher of Andrei Rublev. They also express great love for the ancient civilization and a great interest for its continuation, the Byzantium. Many ask me to be their guide when they visit Greece. They are good-souled people, eager to enrich their knowledge of the Greek civilisation and tranfer it to their own country.

I would like to digress a moment to note that in the basement of the Metropolitical Church of Seoul there are a lot of plaster casts of ancient works of art (donated by Melina Mercouri when she was Culture Minister). They include works of Cycladic, Minoan, Archaic, Classic, Hellenistic, Roman and, of course, Byzantine art that is taught up to date. A result of that teaching is the decoration of the Metropolitan Church of St. Nicholas that was completed in three phases of 20 days each.

Are there similarities between byzantine iconography and Korean traditional painting?

There are indeed some similarities between the Byzantine and the very old Korean and Chineese art. An exemple would be the halo that we find in both Buddha and Jesus. Of course the halo is something that exists since the Hellenistic times, and it is to be found around the heads of Dionysus and Apollo (see the mosaic of the birth of Dionysus, in Paphos, Cyprus) and other Greek Gods. Other similarities would be the fine, clear line, the pastel coulours, the flat surfaces in the dresses and faces. Also, the casual placement of the figures on the surface, like a child who places all figures in the foreground. On the other hand, there are huge differences that have to do with the symbolism and the dogmatic interpretation of the two arts.

*Interviewed by Lina Syriopoulou

TAGS: ARTS | CYPRUS | EDUCATION | GLOBAL GREEKS | HERITAGE | INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | RELIGION