Romeyka is an endangered form of Greek that is spoken by only a few thousand people in remote mountain villages of northern Turkey. It is considered by experts to be a “linguistic goldmine” and a “living bridge” to the ancient world as it has characteristics that have more in common with the language of Homer than with modern Greek.

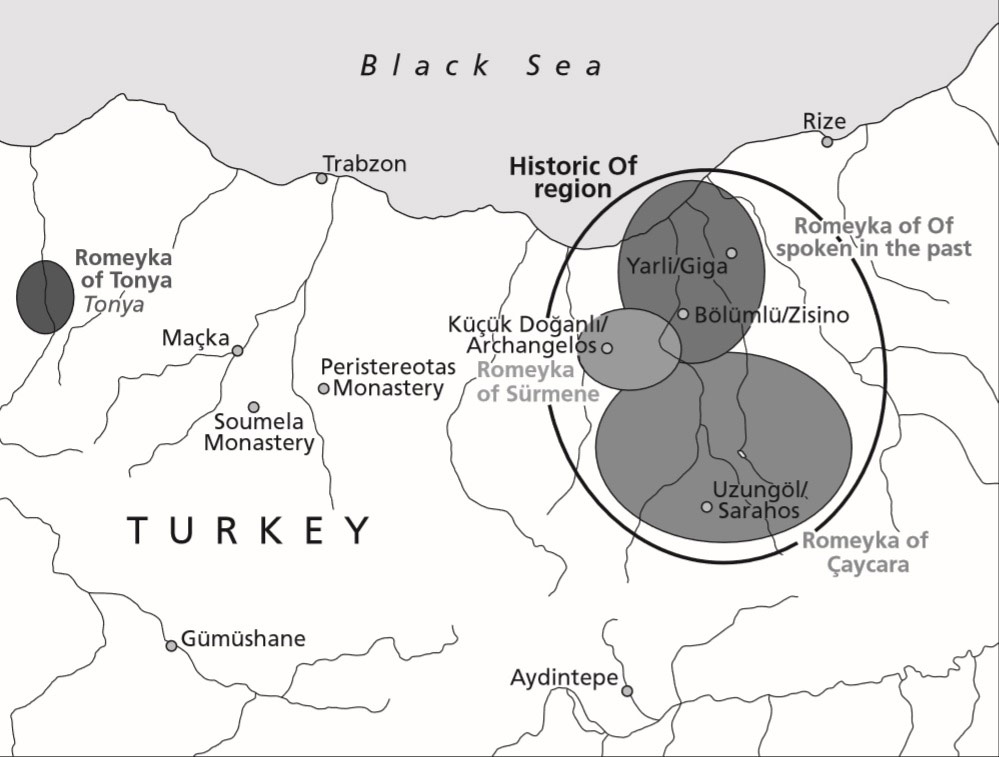

Romeyka is the last surviving variety of Greece spoken in North-Eastern Turkey, in the area traditionally known as Pontus. The precise number of speakers of Romeyka is hard to quantify, but has survived orally in the mountain villages around Trabzon, near the Black Sea coast. Romeyka is thought to have only a couple of thousand native speakers, but the precise number is hard to calculate especially because of the fact that there are also a large number of heritage speakers in the diaspora and the ongoing language shift to Turkish.

Romeyka does not have a writing system and has been transmitted only orally. Extensive contact with Turkish, the absence of support mechanisms to facilitate intergenerational transmission, socio-cultural stigma, and migration have all taken their toll on Romeyka. A high proportion of native speakers in Trabzon are over 65 years of age and fewer young people are learning the language.

As the remaining speakers of the dialect grow older, the language faces the threat of extinction. In response, Ioanna Sitaridou, a professor of Spanish and historical linguistics at the University of Cambridge academic has launched a “last chance” crowdsourcing initiative to document its unique linguistic features before it’s too late, the Crowdsourcing Romeyka project.

The initiative, contributes to the UN’s International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-32), which aims ‘to draw global attention on the critical situation of many indigenous languages and to mobilize stakeholders and resources for their preservation, revitalization and promotion.’

Romyeka Project: an innovative “speech crowdsourcing” tool

The trilingual Crowdsourcing Romeyka platform invites members of the public from anywhere in the world to upload audio recordings of Romeyka being spoken. Ioanna Sitaridou, expects that many contributors will be from the US, Australia, and various parts of Europe. “There is a very significant diaspora which is separated by religion and national identity [from the communities in Turkey], but still shares so much,” she told the Guardian.

“Speech crowdsourcing is a new tool which helps speakers build a repository of spoken data for their endangered languages while allowing researchers to document these languages, but also motivating speakers to appreciate their own linguistic heritage. At the same time, by creating a permanent monument of their language, it can help speakers achieve acknowledgement of their identity from people outside of their speech community,” according to Professor Sitaridou, who has been studying Romeyka for the last 16 years.

The innovative tool is designed by a Harvard undergraduate in Computer Science, Mr Matthew Nazari, himself a heritage speaker of Aramaic. Together they hope that this new tool will also pave the way for the production of language materials in a naturalistic learning environment away from the classroom, but based instead around everyday use, orality, and community.

Important findings: Modern Greek might not be an isolate language

Sitaridou’s most important findings include the conclusion that Romeyka descends from Hellenistic Greek not Medieval Greek, making it distinct from other Modern Greek dialects. “Romeyka is a sister, rather than a daughter, of Modern Greek,” said Sitaridou, Professor of Spanish and Historical Linguistics. “Essentially this analysis unsettles the claim that Modern Greek is an isolate language”. Sitaridou’s findings have significant implications for our understanding of the evolution of Greek, because they suggest that there is more than one Greek language on a par with the Romance languages (which all derived out of Vulgar Latin rather than out of each other).

Over the last 150 years, only four fieldworkers have collected data on Romeyka in Trabzon. By engaging with local communities, particularly female speakers, Sitaridou has amassed the largest collection of audio and video data in existence collected monolingually and amounting to more than 29GB of ethically sourced data, and has authored 21 peer-reviewed publications. A YouTube film about Sitaridou’s fieldwork has received 723,000 views to-date.

In Greece, Turkey and beyond, Sitaridou has used her research to raise awareness of Romeyka, stimulate language preservation efforts and enhance attitudes. In Greece, for instance, Sitaridou co-introduced a pioneering new course on Pontic Greek at the Democritus University of Thrace since the number of speakers of Pontic Greek is also dwindling.

“Raising the status of minority and heritage languages is crucial to social cohesion, not just in this region, but all over the world,” Professor Sitaridou said. “When speakers can speak their home languages they feel ‘seen’ and thus they feel more connected to the rest of the society; on the other hand, not speaking the heritage or minority languages creates some form of trauma which in fact undermines the integration which linguistic assimilation takes pride in achieving”.

Although disentangling the history of the Greek presence in the Black Sea region from legend can be challenging, it is clear that the Greek language spread significantly with the advent of Christianity. “Conversion to Islam throughout Asia Minor often resulted in a shift to the Turkish language, but communities in the valleys managed to retain Romeyka,” Ioanna Sitaridou explained to the Guardian.

In contrast, Greek-speaking communities that remained Christian gradually aligned more closely with modern Greek, especially due to the widespread Greek education in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne resulted in a population exchange between Turkey and Greece based on religious identity, but the Romeyka-speaking Muslim communities in the Trabzon region were not relocated and thus stayed in their homeland. However, extensive contact with Turkish, cultural stigma, and migration have endangered the Romeyka language.

A Romeyka speaker’s view

It is rare for Romeyka speakers to discuss their language publicly. Reflecting on her interactions with Professor Sitaridou, one such speaker, Mrs Havva Sarı, said:

“For me, it is very sad that the Romeyka language is lost, and it is also sad that young people do not speak it. We can only express ourselves with this language. Our jokes, our cries, and our folk songs are all in the Romeyka language. I raised my children in this language because I did not have another language. I would love for them to teach this language to their children, but everyone goes to the cities. They settled down and married people from different cultures. My children’s children cannot speak the Romeyka language anymore, which makes me very sad.”

“I was very happy that there was someone from a different country who showed interest in the Romeyka language. It means that our language is very valuable. Ioanna, who did this research, communicated with me in the same language. I love her like a daughter.”

I.L, with information from Cambridge University, Romeyka.org and the Guardian.

TAGS: GREEK LANGUAGE | HERITAGE