The exhibition Thessaloniki 1922: Monuments and Refugees, takes visitors through the city’s long history as a haven for refugees, focusing on the role of the city’s monuments as shelters. Organised by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki City, on the occasion of the centenary of the Asia Minor Catastrophe, it is hosted at the Rotunda, in the heart of the city, until 31 December 2022.

1912-1922: A pivotal decade for the city

Long after the liberation of Greece, Thessaloniki remained part of the Ottoman Empire. In 1912, Greece along with Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro formed an alliance against the Empire, called the Balkan League; in the ensuing Balkan Wars, the Ottomans lost most of their European territories, with Greece significantly expanding to the north, including Thessaloniki.

As a new territory for Greece, and with most of its Ottoman population leaving the city, Thessaloniki became a pole of attraction for many, at a time when vast populations were persecuted, threatened and/or displaced in the surrounding areas. The city thus welcomed refugees from the Balkans (1912-17), as well as from the heart of the Ottoman Empire during the persecutions of the Greek, Armenian and Assyrian populations (1913-1923), World War I, the Greco-Turkish War which culminated in the Asia Minor Catastrophe (1919-1922) and the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

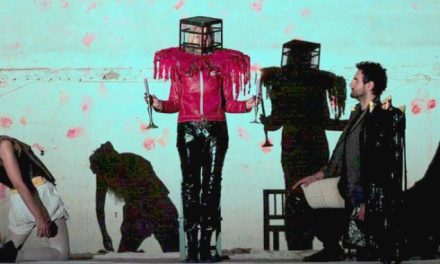

View of the exhibition, chancel of the Rotunda (from the official Facebook page of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki City)

View of the exhibition, chancel of the Rotunda (from the official Facebook page of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki City)

Thessaloniki 1922: Monuments and Refugees

The exhibition Thessaloniki 1922: Monuments and Refugees takes visitors on a journey through the city’s first years as a part of the Greek state. Thessaloniki –dubbed the “refugee capital”– was a haven for many people caught in the whirlwind of early-20th century history of conflicts, state formation and ethnic cleansing in Southeastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

The exhibition traces the refugees’ passage from their places of origin to Thessaloniki, but also focuses on a lesser-known aspect of the city’s history: the role played by monuments during the refugee crisis but also on the historical relics brought along by refugees.

The first section of the exhibition, titled “Refugees in Thessaloniki ‘s monuments”, is thus dedicated to documenting the use of monuments for the accommodation of refugees, through the use of historical photographs, postcards and newspaper clippings.

It traces, for instance, the use of Church of the Acheiropoietos –a three-aisled basilica in the city centre, dating to the 5th century– as a shelter for refugees, first during World War I, the Great Fire of 1917 and the Asia Minor Catastrophe. The church was chosen because it hadn’t yet been consecrated, as there had been plans to re-purpose it as a museum. Refugees also found accommodation in other churches as well as mosques, while some would put up shacks against the medieval walls of Thessaloniki’s Upper Town (Ano Poli).

It traces, for instance, the use of Church of the Acheiropoietos –a three-aisled basilica in the city centre, dating to the 5th century– as a shelter for refugees, first during World War I, the Great Fire of 1917 and the Asia Minor Catastrophe. The church was chosen because it hadn’t yet been consecrated, as there had been plans to re-purpose it as a museum. Refugees also found accommodation in other churches as well as mosques, while some would put up shacks against the medieval walls of Thessaloniki’s Upper Town (Ano Poli).

The exhibition’s second section, titled “Refugee heirlooms”, is dedicated to the relics brought to Thessaloniki by refugees arriving from Eastern Thrace, Constantinople, Smyrna and elsewhere. It showcases family heirlooms including antique books, portable icons and other religious artefacts, belonging to private individuals but also donated to churches by the refugees.

The Rotunda (by Filip Maljković via flickr)

The Rotunda (by Filip Maljković via flickr)

The Rotunda

The Rotunda, which hosts the exhibition, is one of the city’s most iconic monuments; a circular building of around 306 AD, commissioned by Emperor Galerius as part of an imperial precinct linked to his Thessaloniki palace. Originally intended as a temple for Zeus or, according to others, as a mausoleum for Galerius himself (hence the name Tomb of Galerius, by which it known mostly outside of Greece) it was later converted into a church (now consecrated to St George). As shown by the excavations, at the time of its construction the Rotunda and the imperial palace were connected to the Arch of Galerius by a triumphal road. It has undergone extensive restructuring and enlargement over successive periods, and contains some of the most splendid mosaics of early Christian art.

Read also via Greek news Agenda: “Asia Minor Hellenism: Heyday – Catastrophe – Displacement – Rebirth” at Benaki; Early Christian and Byzantine Monuments of Thessaloniki; All of Greece, One Culture | Commemorating the Asia Minor Catastrophe, 1922-2022

N.M.