Ioannis Kapodistrias was the first head of state of Greece. Arguably the most illustrious Greek of his time, he became Governor of the newly-founded independent Greek state after a notable career in international diplomacy. He championed the recognition of Greece’s sovereignty by the Great Powers and worked tirelessly to set the foundations for the nascent republic, although his form of administration prompted controversy among leading figures of the Greek society, culminating in his assassination.

Early life and political career in the Septinsular Republic

Count Ioannis Kapodistrias was born in Corfu on 10 or 11 February 1776 (O.S.). At the time, the island of Corfu formed part of the Venetian Ionian Islands, an overseas possession of the Republic of Venice. His father was Count Antonio-Maria Kapodistrias, a diplomat and politician descending from an old noble Greek family inscribed in the Libro d’Oro of Corfu. His family line can be traced back to at least the 13th century, and is believed to have originated in Constantinople; the family name is a title (Conte Capo d’Istria in Italian) referring to the city of Capodistria (now Koper, modern-day Slovenia), then part of the Republic of Venice. His mother was Countess Adamantine Gonemis, who came from a noble family (also listed in the Libro d’Oro) originating in Cyprus, Crete and Epirus.

In 1794 young Ioannis left for Venice, and studied Medicine, Philosophy and Law at the University of Padua in 1795–97. After obtaining a doctorate in Medicine in 1797, he returned to his native island and worked as a physician and surgeon. He is said to have consistently offered pro bono services to the poor.

Heraldic badge of the Septinsular Republic (1800-1815, via Wikimedia Commons)

Heraldic badge of the Septinsular Republic (1800-1815, via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the Fall of the Republic of Venice at the hands of Bonaparte in May 1797, the Ionian Islands came under the possession of the French Republic. In 1798, a joint Russo-Ottoman campaign was launched against the islands; at some point during the ensuing four-month siege of Corfu, Kapodistrias was briefly appointed chief medical director of the ottoman military hospital.

After the end of French rule, the Ionian Islands were intended to form an independent state, but were eventually reorganised in 1800 as a Russo-Ottoman protectorate, called the Republic of the Seven United Islands (usually referred to as the Septinsular Republic). Two of the delegates, including Ioannis’s father, Count Antonio Maria Kapodistrias, had been entrusted with conducting negotiations with the High Porte in Constantinople; there, they drew up a new constitution, envisaging an aristocratic federal republic with a local administration for every island.

The two envoys returned to Corfu as “Imperial Commissioners”, with the task of overseeing the implementation of the new constitution. In 1801, Ioannis Kapodistrias replaced his father in the position. The reactionary nature of the constitution alienated the populace, and mounting political passions led to general unrest, rebellions and secessionist movements, resulting in Russian intervention in 1802 and the establishment of a new provisional government. In 1803, new electoral colleges, a legislative body and a Senate were created, which passed a more progressive constitution. The Senate appointed Ioannis Kapodistrias Minister of State.

Statue of Ioannnis Kapodistrias in Saint Petersburg (by Egorov.eugene via Wikimedia Commons)

Statue of Ioannnis Kapodistrias in Saint Petersburg (by Egorov.eugene via Wikimedia Commons)

In March 1802, Kapodistrias had founded the College of Medicine (Collegio Medico) in Corfu, a medical association (the first of its kind in any part of Greece). As a member of the government, he undertook initiatives to establish a system of public education –virtually non-existent until then– and in 1805 founded the Archigymnasion, the first Greek school of public service.

In 1807, the Ionian Senate entered the War of the Fourth Coalition on the side of Russia, and the Ali Pasha of Yanina took the opportunity to attack the islands, besieging Lefkada. Kapodistrias was named Commissioner Extraordinary of the island’s fortification programme. Several klepht captains from the mainland, including Katsantonis and Kitsos Botsaris, took part in the defence of Lefkada. This led to the first acquaintance of Kapodistrias with some of the chief military leaders of the subsequent Greek War of Independence. At the end of the war, the Septinsular Republic was annexed to France.

Russian diplomatic service

In 1808, Kapodistrias was informed by the Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire that he had been awarded the Order of St. Anna, 2nd class, and he was invited to St. Petersburg. In 1809, he entered the service of Alexander I as State Councillor. After two years in St. Petersburg, he was transferred to Vienna as Embassy Secretary in 1811, and then to Bucharest as Head of the diplomatic office of the commander of the Danube Army in 1812. That same year he was appointed Chancellor of State in service and was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir, 3rd class. In 1813 he was presented with the Order of St. Anna, 1st class.

In 1813, he was the Tsar’s special envoy to Switzerland, with the objective of acting as an unofficial mediator between the cantons in their negotiations that lay the foundations for the creation of the Swiss Confederation. He also played an important part in drafting the Federal Constitution. In the 1814-15 Vienna Congress and the 1815 Paris Conventions he was instrumental in the integration of Geneva to the Swiss Confederation, and the formal acknowledgement of the perpetual neutrality of Switzerland. In 1816 he became the first person to attain the title of honorary citizen of the city of Lausanne.

Left: Portrait of Ioannnis Kapodistrias by Thomas Lawrence, 1818/1819, (Royal Collection via Wikimedia Commons); right: Anthimos Gazis (via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Portrait of Ioannnis Kapodistrias by Thomas Lawrence, 1818/1819, (Royal Collection via Wikimedia Commons); right: Anthimos Gazis (via Wikimedia Commons)

While in Vienna as a member of the Russian delegation to the 1814-15 Congress, Kapodistrias was approached by Greek scholar and cleric Anthimos Gazis, who resided in the city (an important centre of the Greek diaspora at the time). Gazis informed him about the founding of a “Philomuse Society” in Athens the previous year, with the purpose of promoting the preservation of the antiquities, but also of advancing the education of young Greeks; the society received the direct support of British diplomats and philhellenes. Kapodistrias decided to found a Philomuse Society in Vienna, with the main purpose of aiding young Greeks to pursue a “European education”, and the Tsar’s endorsed it as a means to counter British influence in the Balkans.

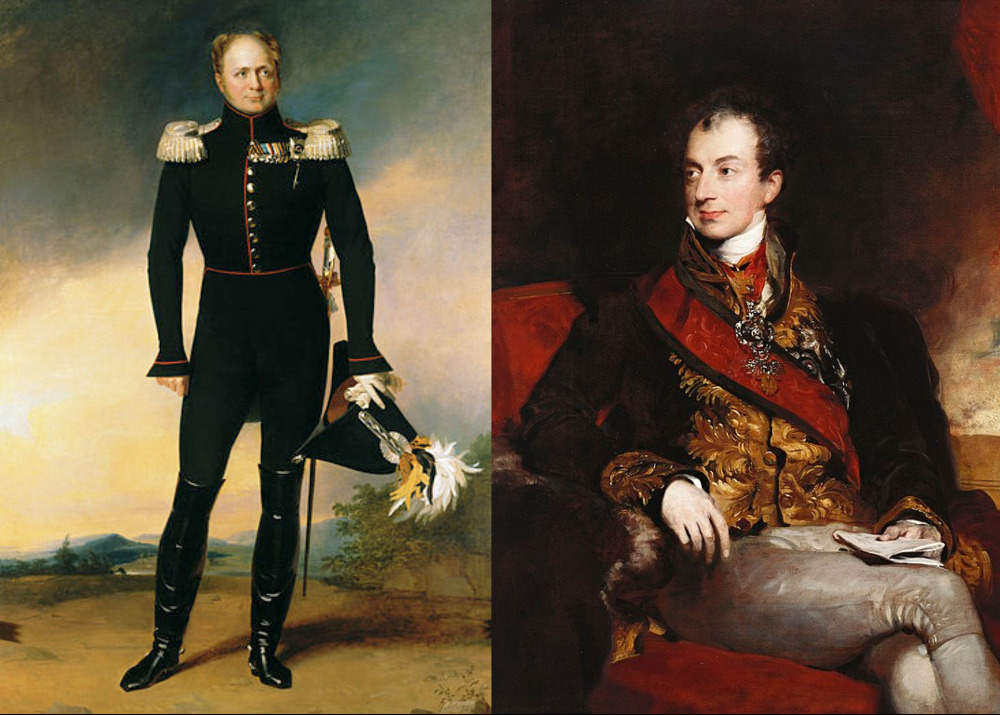

Following his diplomatic successes, Alexander I appointed Kapodistrias State Secretary in charge of Foreign affairs jointly with Karl Robert Nesselrode. As of 1816, Kapodistrias would act as de facto Foreign Minister of Russia alongside Nesselrode. While in office, Kapodistrias became known for his liberal ideas, and he came to represent a progressive alternative to the conservative influence of the Austrian foreign minister Prince Metternich.

Metternich was a central figure of the Holly Alliance, a coalition linking the monarchist Great Powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia at the wake of Napoleon’s defeat; he promoted the aggressive suppression of the various liberal and nationalist movements and popular uprisings in Europe, in the interest of maintaining the balance of power, peace and the existing unity among the Great Powers. Kapodistrias instead advocated a less rigid stance, believing that yielding to some moderate demands of the bourgeoisie would be more effective in achieving a lasting peace. Despite Alexander’s trust in Kapodistrias, Metternich would eventually maximise his own influence over the Tsar.

Left: Portrait of Alexander I. Emperor of Russia by George Dawe, 1826, Peterhof Palace (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Portrait of Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich by Thomas Lawrence, 1815 (Royal Collection via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Portrait of Alexander I. Emperor of Russia by George Dawe, 1826, Peterhof Palace (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Portrait of Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich by Thomas Lawrence, 1815 (Royal Collection via Wikimedia Commons)

In January 1817, an emissary from the secret Greek revolutionary organisation Society of Friends (Filiki Eteria) arrived in St. Petersburg to offer Kapodistrias the leadership of the movement. Kapodistrias declined, deeming the goal of Greek liberation honourable but entirely unachievable. He remained adamant in his refusal when he was twice more approached by members of the Society, with requests for Russian support of a Greek uprising; he also advised Prince Alexander Ypsilantis, senior officer of the Russian Army and leader of the Society, whom he deeply esteemed, to abandon his plans which he believed were doomed to fail miserably.

In 1819, Kapodistrias made an unsuccessful effort to persuade the British government to withdraw Sir Thomas Maitland from the position of Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands (which, since the fall of Napoleon, had become a federal republic under the “amical protection” of the UK), due to the local population’s deep dissatisfaction with his form of government.

Kapodistrias formed part of the Russian delegations to several important congresses such as those convened in Aachen (1818), Troppau (1820) and Laibach (1821). At the Laibach Congress, the European leaders received the news of Ypsilantis’s invasion of the Danubian Principalities, which heralded the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence. Kapodistrias was utterly surprised by the development, and addressed a letter to Ypsilantis refusing any support from Russia.

Left: Ioannis Kapodistrias, 1820s (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Alexander Ypsilantis crossing River Pruth into the Danubian Principalities by Peter Von Hess, (via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Ioannis Kapodistrias, 1820s (via Wikimedia Commons); right: Alexander Ypsilantis crossing River Pruth into the Danubian Principalities by Peter Von Hess, (via Wikimedia Commons)

Soon, however, the Ottomans’ harsh reprisals against the Greeks of Constantinople –notably, the public execution of Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V in April 1821, on an Easter Sunday– forced Alexander to present the High Porte with an ultimatum, drafted by Kapodistrias, proclaiming that the Sultan’s actions had “legitimised the defence of the Greeks”, obliging Russia to help its Christian brothers against persecution. Following the Port’s disregard of the ultimatum, Russia broke off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire.

Alexander was however reluctant to take steps to actively protect the Greek population from Ottoman attacks, fearful of a war with the Ottomans and sympathising with Metternich’s stance. Kapodistrias found himself torn between his patriotic duties and desires and his duty to the Tsar; in a private meeting with him in 1822, he exposed his situation. Alexander did not accept his resignation, not wanting to attract attention to internal dissent in his government, but instead placed him on an extended leave of absence for “medical reasons”.

Kapodistrias retired to Geneva, where he was cordially received due to his previous role in the formation of the Swiss Confederation, and remained there for the greater part of the following five years. There he received news of the developments of the revolution, and functioned as an advocate of the Greek cause, raising funds for the war-stricken population and meeting with important figures such as Stratford Canning.

Governor of Greece

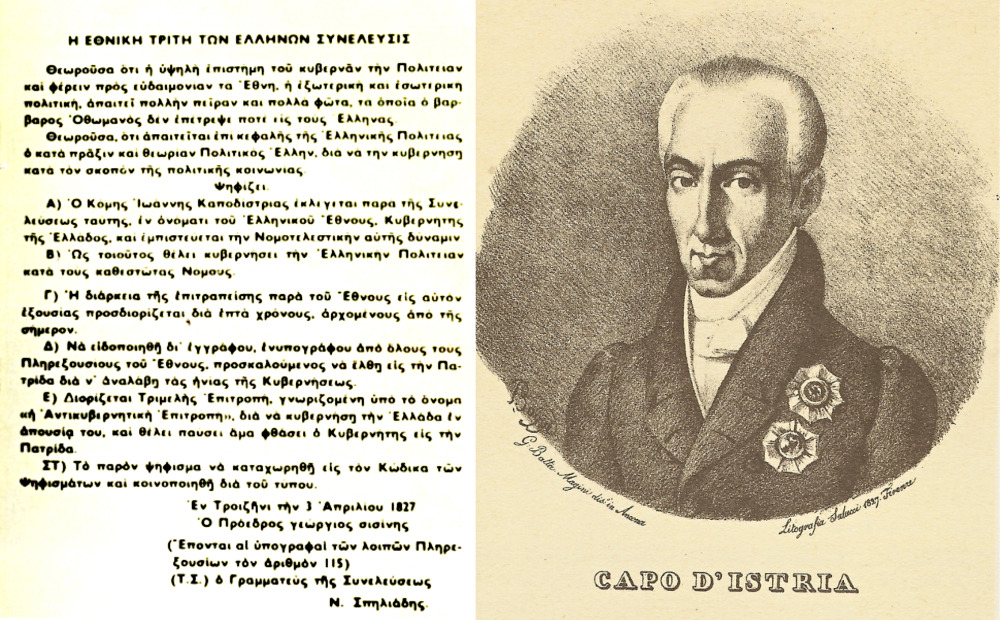

Several members of the Provisional Administration of Greece had, since the early stages of the Greek Revolution, considered the idea of appointing Kapodistrias to a leading position. Finally, in April 1827, at the Third National Assembly at Troezen, they officially established the office of Governor, and elected him for a seven-year term. They also approved the Political Constitution of Greece, by which the Governor would be bound.

The text of the April 2nd, 1827 Resolution of the Third Greek National Assembly at Troezen, appointing Ioannis Kapodistrias Governor of Greece for a seven-year term (via Wikimedia Commons)

The text of the April 2nd, 1827 Resolution of the Third Greek National Assembly at Troezen, appointing Ioannis Kapodistrias Governor of Greece for a seven-year term (via Wikimedia Commons)

Kapodistrias was informed of his appointment while in Geneva and, before accepting it, travelled to St. Petersburg to officially disengage himself from the service of the Tsar. Over the following months he toured Europe to rally support for the Greek cause, and finally landed in Nafplion in January 1828, where he was received enthusiastically. The situation he encountered was nevertheless disheartening, since Greece was still ravaged by war and poverty, as well as by the ongoing rivalries between different factions of revolutionary leaders.

Kapodistrias declared the foundation of the Hellenic State; he created and organised regular forces, placing Sir Richard Church (ex-military British officer), Demetrios Ypsilantis (ex-Imperial Russian Army like his brother Alexander) and Augustinos Kapodistrias (his own brother) as commanders-in-chief; he also set Andreas Miaoulis as his Admiral, and assigned him the task of countering piracy.

One of his first priorities was the establishment of the first National Bank of Greece. In April 1828 he signed a decree authorising the minting of the phoenix, the first national currency of Modern Greece. He also founded the first printing house on the island of Aegina (then provisional capital of Greece) as well as the first Archaeological Museum. In 1829 he made Nafplion the capital of Greece, where he also founded the Hellenic Army Academy.

He was not satisfied with the terms of set by the first London Protocol signed by the three Great Powers on November 1828, which limited the tributary Greek state to the Peloponnese and the Cyclades islands. He instructed his generals to continue warfare in Central Greece, despite calls by the new British ambassador Edward Dawkins and Admiral Malcolm to retreat the Greek forces to the Peloponnese. He had also supported two campaigns undertaken by Greek and Philhellene soldiers to capture Chios and Crete, which however proved fruitless.

Left: Bust of Ioannis Kapodistrias in the National Garden of Athens (by Stolbovsky via Wikimedia Commons); right: Statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias in front of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (by C messier via Wikimedia Commons)

Left: Bust of Ioannis Kapodistrias in the National Garden of Athens (by Stolbovsky via Wikimedia Commons); right: Statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias in front of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (by C messier via Wikimedia Commons)

Kapodistrias also engaged in tireless diplomatic efforts to gradually widen Greece’s borders and increase its recognised independence, aided by the Greek and French army’s advance in Central Greece and the Peloponnese, respectively, and taking advantage of each Great Power’s aspiration to control the influence of the rest of the powers in the Balkans. In the third London Protocol, signed on 3 February 1830, Greece was recognised as an independent, sovereign state.

Regarding his policy in state affairs, Kapodistrias had asked the Senate to give him full executive powers and to have the constitution suspended while the Senate was to be replaced with a Panhellenion, whose 27 members were all to be appointed by the Governor. His administration was influenced by his sympathy for the ideas of enlightened absolutism; this approach was further cemented by his distrust towards the various factions of the revolutionary forces, who he believed might be motivated by opportunism, as well as the complete lack of infrastructure and national coordination in the country, which created the need to build a state from the ground up.

Kapodistrias took over the task of the reconstruction of ravaged cities and a waning economy. He set the grounds for the Hellenic state’s first education and welfare systems, founding monitorial schools (i.e. schools employing the “mutual instruction system”), crafts schools and the country’s first organised orphanage. He also established the first model farm and School of Agriculture, close to the city of Nafplion. He showed particular interest in boosting agriculture, since most Greeks at the time were farmers, and introduced new crops (such as the potato), while he also supported and subsidised shipping and the construction of shipyards on the islands.

He also laid the foundations for a judicial and public administration system, introducing a Code of Civil Procedure and a set of laws, establishing courts of first instance in the seats of the prefectures, local courts in the towns, and courts of appeal. Despite his efforts, he was not able to secure loans from foreign banks; he did however receive financial aid from foreign governments, especially Russia and France. He even used his personal fortune to contribute financially to the many needs of the Greek state, while also refusing to receive any salaries as a Governor.

The assassination of Ioannis Kapodistrias by Charalambos Pachis, Corfu Municipal Library (via Wikimedia Commons)

The assassination of Ioannis Kapodistrias by Charalambos Pachis, Corfu Municipal Library (via Wikimedia Commons)

Controversies and Assassination

Despite his many efforts, the nascent Greek state faced multiple problems on all fronts. The economy remained weak and, although Kapodistrias was loved by the common people, his autocratic style of government had alienated many former leaders of the Greek Revolution, who wished to have a more decisive part in state matters, and especially the kodjabashis, local rulers who had accrued substantial power under Ottoman rule and were reluctant to give up their prerogatives. Local, factional and clan rivalries were often exacerbated by foreign actors who sought to further the influence of their respective countries. Liberals were also disappointed by his reluctance to draw up a constitution and call a national assembly.

Hydriot ship-owners were particularly incensed with the Governor’s reluctance to offer them financial reparations for their extensive (practical and economic) contribution to the Greek War of Independence; given the dire economic situation of Greece, Kapodistrias had chosen to direct the state’s limited resources to more pressing matters, and delayed these compensations.

He also faced stark opposition by the Mavromichalis family, a large and prominent clan who acted as rulers (bey) of the semi-autonomous Mani Peninsula in the Peloponnese. The family refused to give up their privileges and authorities to the central government, and incited an open rebellion in Mani against Kapodistrias in 1830. Some of them were arrested and put to prison, which further fuelled their animosity and was viewed as an insult to their honour. On 27 September 1831 (O.S.), the Governor was assassinated by two members of the family in the city of Nafplion, on his way to Sunday mass.

He was succeeded in the office by his brother Augustinos, who resigned six months later; a series of collective governing councils were then established, but civil strife plunged Greece into confusion, until the Great Powers designated Prince Otto of Bavaria to become Greece’s first Monarch in 1832.

Sources (in Greek):

Ioannnis Kapodistrias Digital Archive (John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation)

Ioannnis Kapodistrias (“Switzerland and Greece”; Official page of the Swiss Confederation)

“Ioannnis Kapodistrias. His path in time” (historical blog)

Ioannnis Kapodistrias (Argolikos Archival Library of History and Culture)

“Kapodistrias’ diplomatic struggles for the demarcation of the borders of the modern Greek state” (paper by Kostas Hatziantoniou presented at the Conference “Rigas Ferraios, Ioannis Capodistrias, Francisco de Miranda”)

Ioannnis Kapodistrias (Wikipedia)

The Government of Ioannnis Kapodistrias (Wikipedia)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: 3 February 1830: Greece becomes a state; “Greece 2021” | The celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the country’s Independence War; Greek Independence Day: 25 March, 1821 | The Making of a Modern European State; Alexander Ypsilantis, a leader of the Greek Revolution; Theodoros Kolokotronis: The archetypal Greek hero; A New Digital Archive for Greece’s First Governor, Ioannis Kapodistrias

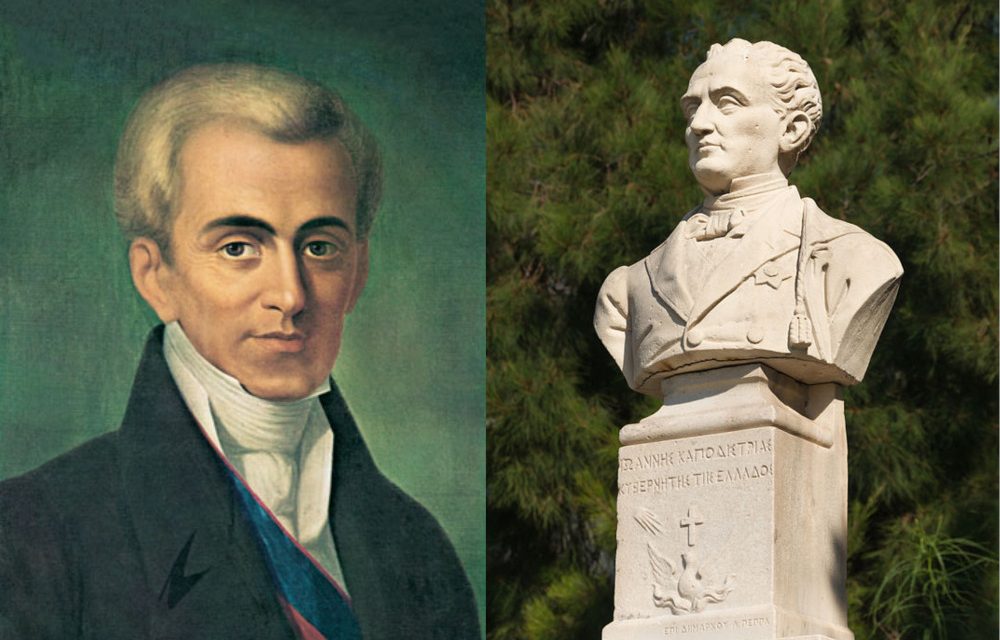

N.M. (Intro, Left: Portrait of Ioannnis Kapodistrias by unknown author, National historical Museum of Athens [via Wikimedia Commons]; Right: Bust of Ioannis Kapodistrias by Karakatsanis, 1887, on the island of Aegina [by Jebulon via Wikimedia Commons])