The Civil Rights Movement was one of the most important political movements in American history. It was the reaction of the Black community to systematic racial discrimination, and resulted in the passing of landmark laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Martin Luther King Jr. stood out among several leading figures of the community who emerged in that period.

While many were those who opposed the movement, choosing to uphold the status quo, others were supportive of the Black Americans’ struggle to gain equal rights under the law. Greek Americans were, traditionally and to a great extent, supportive of the African American cause; after all, Greeks in the USA had themselves fallen victims to discrimination in earlier times, especially in the Southern states, where people of Greek origin were, among several other races and ethnicities, targeted by the KKK.

Archbishop Iakovos and the march in Selma

At the height of the civil rights movement, the African American cause found a spirited ally in the face of one of the most eminent and influential figures of the Greek community in the USA: Iakovos, Archbishop of the Greek Orthodox Church of North and South America.

Archbishop Iakovos (1911–2005), who had, from a young age, experienced discrimination as a member of the Greek minority in the Ottoman Empire, had always been a champion of freedom, equality and integration. Already in 1958 and in 1962, the Director of Public Relations of the Archdiocese had written, on behalf of Iakovos, (in letters addressed to a theology student and to a researcher, respectively), that the Greek Orthodox Church was ” without prejudice in reference to race or color” and stood “unequivocally against segregation of any kind”.

Archbishop Iakovos marches with Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy on 15 March 1965 (from Penn State Special Collections via flickr)

Archbishop Iakovos marches with Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy on 15 March 1965 (from Penn State Special Collections via flickr)

On 28 September 1963, the Archdiocesan Central Council of the Archdiocese passed a resolution on racial equality, signed by Iakovos, condemning segregation and racial bigotry. Then, in April 1964, while the Civil Rights Bill was discussed in the Senate, the Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas, chaired by Iakovos, issued a statement against racial bigotry, pointing out that “persecution, prejudice and intolerance is the greatest sin that the free soul of man can bear”.

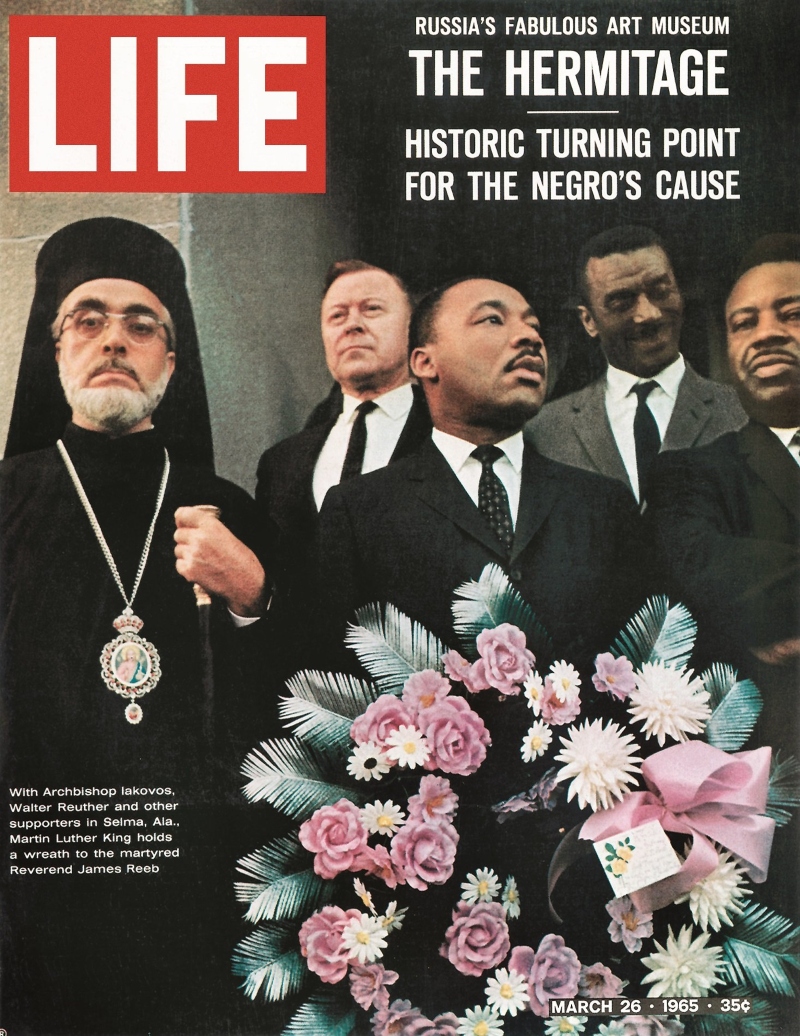

In 1965, when state troopers killed activist Jimmie Lee Jackson by at a demonstration in Selma, Alabama, a voting rights march was held from the city to the state capital, Montgomery, to confront Alabama’s segregationist Governor George Wallace about the event. After the first March, on 7 March, was violently suppressed by police, a second one was led by Rev. Martin Luther King, two days later. James Reeb, a white minister and civil rights activist, who had participated in the second march, was beaten to death by Ku Klux Klan members that same evening, causing a national outcry against white supremacist violence; on 15 March, a memorial service for Reeb was held at the Brown’s Chapel AME Church.

Iakovos, along with his Chancellor Fr. George Bacopoulos and several other clergymen from the Commission on Religion and Race, flew to Alabama and attended the service, although his advisors’ strong reservations about safety; he was the highest ranking clergyman present. The crowd then walked in procession to the Dallas County Courthouse. Martin Luther King Jr. led the march with Iakovos and Reverend Ralph Abernathy beside him. As they reached the courthouse, those at the head of the procession walked up to the steps at the closed entrance to address the large crowd. This moment was captured by a Life magazine reporter, and the photograph appeared on the cover of the March 26, 1965 issue.

Cover of a Life magazine’s March 26, 1965 issue featuring Archbishop Iakovos, Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy and Walter Reuther at James Reeb’s memorial service (source: SNF)

Cover of a Life magazine’s March 26, 1965 issue featuring Archbishop Iakovos, Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy and Walter Reuther at James Reeb’s memorial service (source: SNF)

As the New York Times would report, the “striking cover of [Life] magazine that showed Dr. King side by side with the black-garbed Archbishop Iakovos marked a new presence of Greek Americans and the Greek Orthodox church in American life”.

In a statement issued following the memorial service, Archbishop Iakovos said that he went because he believed that was “an appropriate occasion not only to dedicate [him]self as well as [the] Greek Orthodox Communicants to the noble cause for which […] Reeb gave his life; but also in order to show [their] willingness to continue this fight against prejudice, bias and persecution”. That same evening, President Lyndon Johnson addressed the Congress in support of a Voting Rights Bill; the following day, Iakovos sent him a telegram to express feelings of gratitude on behalf of his people for “marking the dawn of a new era of the American Democracy”.

The Archbishop’s public stance was met with generally positive reactions from USA’s Greek Orthodox community; although the Archdiocese did receive several letters from parishes in southern states voicing concerns over economic reprisals against local Greek communities (who mainly relied on businesses such as restaurants), most of the letters and telegrams (especially from northern states) expressed enthusiasm over his actions, finding them to be true to the spirit of Christianity and orthodoxy but also of “the American promise”.

Iakovos remained a lifelong foe of racial intolerance. He opposed the Vietnam War, voiced support for Soviet Jews’ rights and tried to influence Arab Christians to work for peace in the Mideast. In 1980, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, one of the two highest civilian awards of the U.S., by President Jimmy Carter. In his remarks, delivered at the presentation ceremony, the President described the Iakovos as a “progressive religious leader concerned with human rights”, admired by Greek Americans as well as by the Carter himself, noting that the Archbishop “ha[d] long put into practice what he ha[d] preached”.

Martin Luther King III, Bernice Albertine King and Archbishop Demetrios of America at an event for the 50th Anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery Marches (© the website March on Selma – Orthodoxy and the Civil Rights Movement)

Martin Luther King III, Bernice Albertine King and Archbishop Demetrios of America at an event for the 50th Anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery Marches (© the website March on Selma – Orthodoxy and the Civil Rights Movement)

Half a century later, at the commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery Marches, Archbishop Demetrios was among the distinguished guests who delivered his own remarks, while the Archdiocese also launched a website dedicated to its long support of the Civil Rights Movement.

Contributions of everyday Greek-Americans

Although, among the examples of Greek American support for desegregation and racial equality, the one set by Archbishop Iakovos was by far the most famous and prominent, there were several smaller ones, usually not known beyond local communities, and thus more difficult to identify and document.

Such was the case of Alex Gulas, a native of Birmingham, Alabama, with a long career in the restaurant and entertainment business. Among his ventures was the establishment of the Key Club, where he played an instrumental role in integrating the jazz industry in the state, even though the city which was segregated at the time, with the KKK exerting great influence on the authorities. For this, he inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame in 1991, after having been nominated by Avery Richardson, one of the many black musicians who had played at the club.

Photograph of a Greek-owned dinner serving black customers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (possibly in the 1920s or 1930s; source : Shorpy.com)

Photograph of a Greek-owned dinner serving black customers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (possibly in the 1920s or 1930s; source : Shorpy.com)

An article in the 8 Dec 1961 issue of Life magazine (p.p.38-39) also documents the case of Anthony (Tony) Konstant from Baltimore, who owned a restaurant on Route 40. All the restaurants and bus terminals on the highway in the state of Maryland served only white customers, and were thus targeted by the civil rights activist group “Freedom Riders” in 1961. Although the White House and State Department became involved in the matter, restaurant owners resisted change, and desegregation bills were blocked in the state legislature. When the debate seemed to reach an impasse, a “Committee of Eight” restaurateurs, chaired by Konstant, began meetings and intensive negotiations with the rest of restaurant owners in the area in November of 1961, finally persuading almost half of them to desegregate their eateries. In 1962, the Maryland General Assembly would finally pass an anti-discrimination bill.

In more recent times, it is worth noting that, in celebration of the bond between the Greek and African American communities, Anthony Brown, then Maryland’s Lieutenant Governor, presented a Proclamation designating 27 March 2013 a day dedicated to the unity of the two communities, following a partnership between the American Hellenic Progressive Association (AHEPA) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to combat bigotry. On this occasion, an event took place at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History in Baltimore.

Watch a video created by the Hellenic American Leadership Council (HALC) and the Embassy of Greece in Washington on the occasion of Black History Month on the occasion of Black History Month.

Reads also via Greek News Agenda: Louis Tikas: a Greek-American trade union hero; Rethinking Greece | Antonis Chaldeos on the Greeks of Africa

N.M.

TAGS: GLOBAL GREEKS