In her feature for Greek News Agenda, Dr. Alexandra Kouroutaki writes about Christmas iconography, especially the Nativity scene, as depicted in both icons and frescoes of the 20th century in historical temples of the region of Chania, focusing on the Western (modern) and traditional elements found in these works.

Alexandra Kouroutaki works as a Lab and Teaching staff (EDIP member) at the School of Architecture, Technical University of Crete. She holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, and a Postgraduate Diploma in French Literature from the School of Humanities of the Hellenic Open University, and is an honours graduate of the Department of French Language and Literature of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Christmas; who can remain indifferent to the Birth of the son of God? The scene of the Nativity, the Shepherds’ pilgrimage and the adoration of the Magi, as depicted in both icons and frescoes in historical temples of the region of Chania, presents an occasion for an interesting overview of homegrown hagiography. In particular, it gives the creative imprint of an inspirational religious art in Chania of the 20th century, an extremely interesting time for the development of hagiographic art. The purpose of this study is to explore the paths taken by these hagiographers and to highlight the Western (modern) and traditional elements in their works, both in terms of iconography and style.

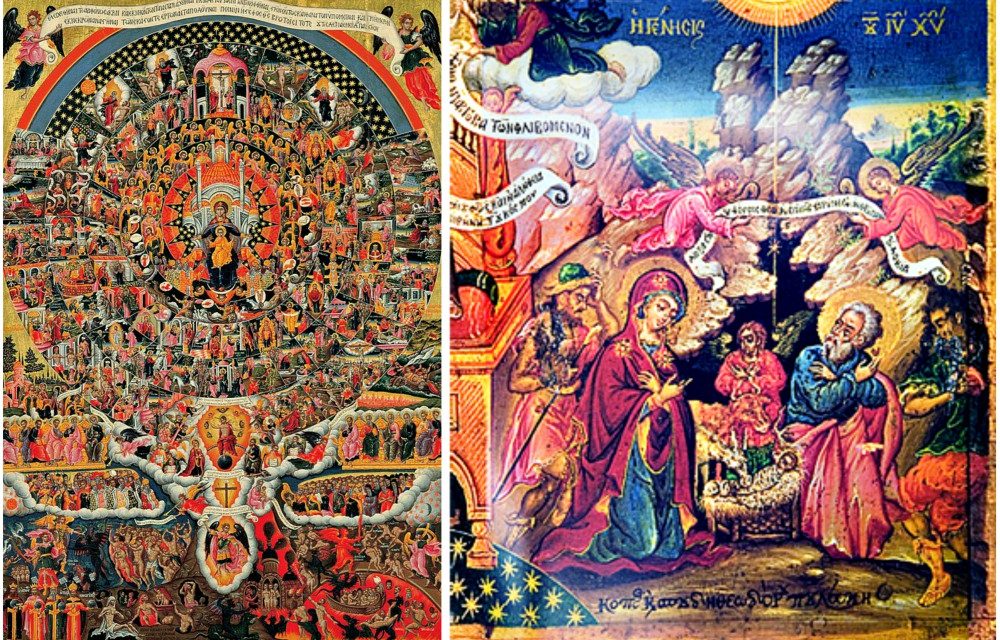

In this context, there is initially a brief historical overview regarding the adoption of Western models in Orthodox hagiography in Crete, with reference to the Cretan (from Kydonia, Chania) post-Byzantine iconographer Theodoros Poulakis, who is considered one of the most important artists of the Cretan School. This is followed by a presentation of the movement of artistic ideas in hagiography in the early decades of the 20th century, highlighting the influence of Nazarene-neorenaissance art and the art of Mount Athos on hagiographers from Chania.

Finally, hagiography’s shift after 1950 towards Byzantine tradition is examined, as well as church frescoes of the Nativity in Chania, painted by students and associates of Fotis Kontoglou and continuators of the tradition of the Cretan school of hagiography.

Alexandra Kouroutaki

Alexandra Kouroutaki

1. Historical perspective: The adoption of western elements in Orthodox religious painting in Crete

The introduction of western figurative templates in Orthodox religious painting in Crete was the result of the influence of developments in Western European art during the Renaissance on Cretan hagiographers. In Venetian-occupied Crete, the painting of religious icons gains considerable momentum[1]. The work of indigenous artists was infused with elements of Western art as early as the second half of the 15th century[2], continuing through the 16th century with the leading hagiographers of the Cretan School, Theophanes, Michael Damaskinos and Georgios Klontzas. The Cretan school of hagiography will develop a unique style under the impact of both eastern and western influences, combining Byzantine tradition with realism and elements of naturalness[3] characterising Western painting.

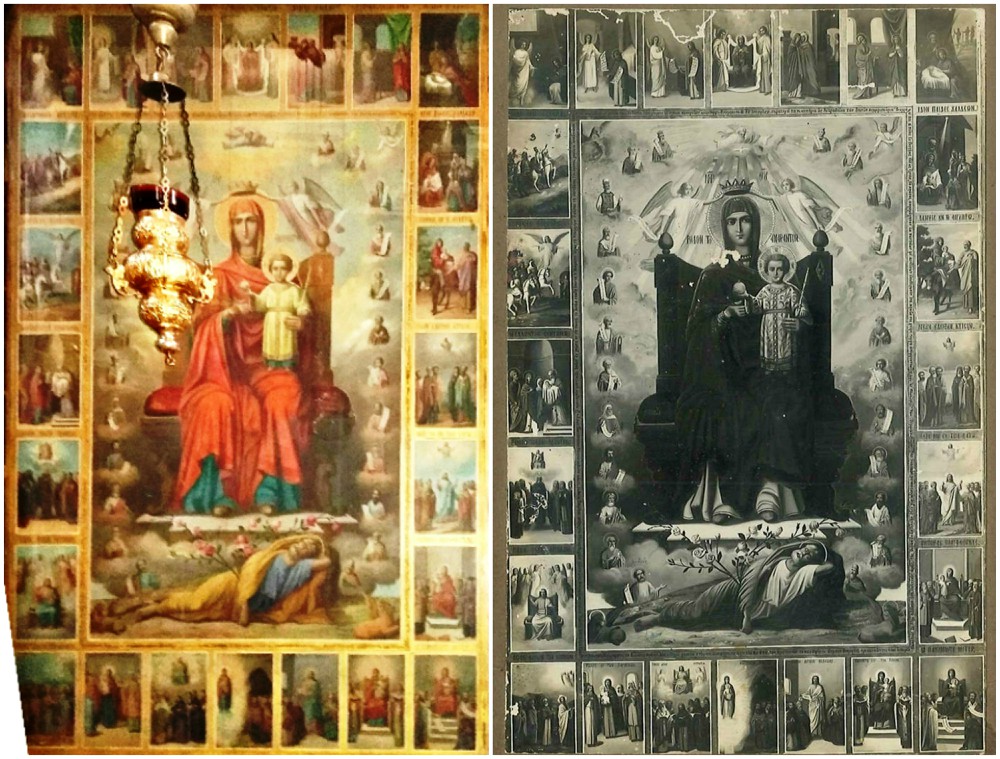

The opening towards Italian artistic modes became more intense in the course of the 17th century. Of note is the case of the progressive post-Byzantine iconographer Theodoros Poulakis (1622-1692) who mentions the region of Kydonia in Chania as his place of origin in the icon Epi Si herei (All creation rejoiceth in thee)[4]. It is an intricate, signed icon centred on the figure of the Virgin Mary and Child and scenes from the Passion of the Christ and the Old Testament in circular order. A major example of miniature art, the icon also includes the Nativity scene. Poulakis upholds Byzantine standards but incorporates an abundance of western influences in his iconography, including: expressive postures and movements of figures, realistic processing of details such as fabric folds, the use of bright and glowing colors and the perspective rendering of space are influences that the artist accepted from western art, and in particular from Baroque and the naturalism of Flemish painters[5].

Poulakis uses the egg tempera painting technique in wood and he was not interested in oil painting. He contributed significantly to the establishment of European aesthetics in Orthodox religious painting, a tendency enshrined in the Ionian School of Hagiography.

Left: Stylianos Perrakis, Rodo to Amaranto, Right: Stylianos Perrakis, Rodo to Amaranto (1928)

Left: Stylianos Perrakis, Rodo to Amaranto, Right: Stylianos Perrakis, Rodo to Amaranto (1928)

2. The influence of Nazarene style and the art of Mount Athos on religious painters in Chania[6]

The Nazarene style was “imposed” in Greece under Otto’s political leadership in the context of the secularisation of religious art and the general attempt to Europeanise the newly established Greek state. Nazarene religious art influenced Cretan hagiographers as well[7]. The coexistence of indigenous hagiography with western Nazarene art contributed to its further distancing from traditional Byzantine models. The move towards neo-Renaissance concepts was also reinforced by the apprenticeship of many indigenous painters-hagiographers at Mount Athos, mainly during the first three decades of the 20th century. In the art of Mount Athos, both iconographic types and color scale were influenced by Nazarene painting and western Russian art[8]. In the interwar period, two well-known hagiographers from Chania, Stylianos Perrakis and Georgios Polakis, produced rich hagiographic work. They were influenced by the western mode of Mount Athos art of the time and adopted elements of Nazarene art. Their works adorn many churches in the city and prefecture of Chania[9].

In Stylianos Perrakis’ icon, Rodo to Amaranto (Unfading Rose) 1928, which adorns the Church of St. Nicholas in the area of Splantzia, Chania, the hagiographer depicts the Nativity scene in the upper right corner and under this the Adoration of the Magi. The hagiographer follows western standards in his iconography and adopts a naturalistic approach. In the centre of Perrakis’ icon, the figure of the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus is surrounded by angels. Surrounding the central figure are scenes from their lives. Perrakis’ “Nazarene” style of painting maintains the sanctity of Byzantine art, while also seeking technical perfection, emphasising color variation, perspective and structure principles established by the Renaissance. Perrakis’ technique follows the Nazarene Western style and he replaces egg tempera with oil.

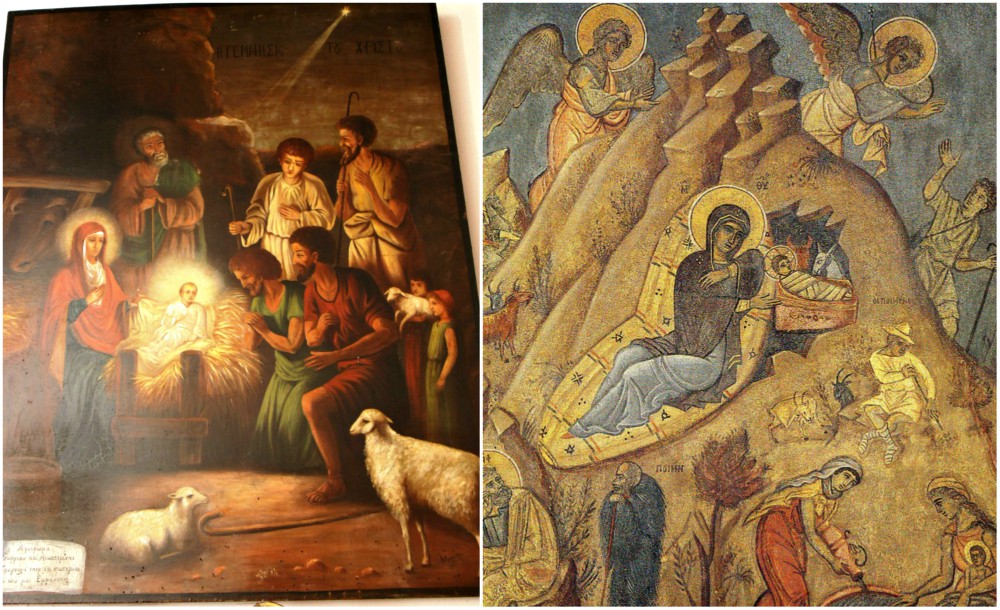

Georgios Polakis, Nativity

A well-known hagiographer during the interwar period, influenced by the Western-style art of Mount Athos[10], was Georgios Polakis (1880-1951), a native of Kefali of the Nine Villages of Kissamos, in Chania. He attended the School of Fine Arts and studied the current Mount Athos style of painting on the Holy Mountain (1900-1905)[11]. He practiced the Neo-Renaissance style in his hagiographies, in the context of academicism. In the icon of the Nativity that adorns the iconostasis of Saint Constantine church, Polakis draws his iconographic templates from the West. The figure of the Virgin Mary is presented in the foreground, kneeling towards the Divine infant. Mary is surrounded by Joseph who is portrayed thoughtful, and four angels, kneeling in awe. Outside the cave-manger, an angel announces the miracle to the shepherds. Polakis depicts his figures with plausibility and realism. The technical excellence, the elaborate drawing and the use of bright and harmoniously blended colors characterise the whole work.

The portable icon that adorns the Church of St. Demetrios in Ano Platanias, Chania, painted by the iconographer Ch. Progoulis, depicts the scene of adoration of the shepherds in a cave. The central figure of baby Jesus dressed in white is depicted sitting in a manger filled with hay, with a halo above his head. The wrapped infant reminds of the dead in burial shrouds, of the death and the burial of Jesus for the salvation of men. The hagiographer adopts a naturalistic approach, using bright and harmoniously combined colors.

Left: Ch. Progoulis, Αdoration of the shepherds, Right: F. Kontoglou, Nativity of Christ

Left: Ch. Progoulis, Αdoration of the shepherds, Right: F. Kontoglou, Nativity of Christ

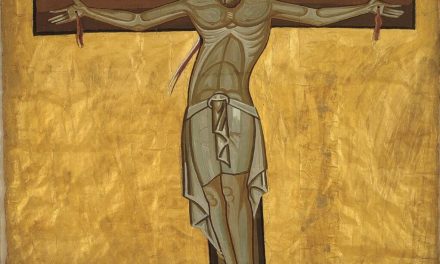

3. The shift of Religious painting towards Byzantine tradition sources

The shift from the principles of naturalistic art to Byzantine figurative styles began taking place in Greece and Crete since the ΄50’s, under the heavy influence of Fotis Kontoglou who followed that direction[12]. Thanks to Kontoglou, a revival of Byzantine iconography was set in motion. This shift was accompanied by the return to the egg tempera technique which replaced oil painting. In his ecclesiastical art, Kontoglou continued the post-Byzantine tradition and created with his students a large number of icons. Kontoglou depicts with devoutness the Nativity of Christ[13] in the fresco paintings in the church of Zoodochos Pigi, in Liopesi and in the chapel of the house of Pemazoglou in Kifissia.

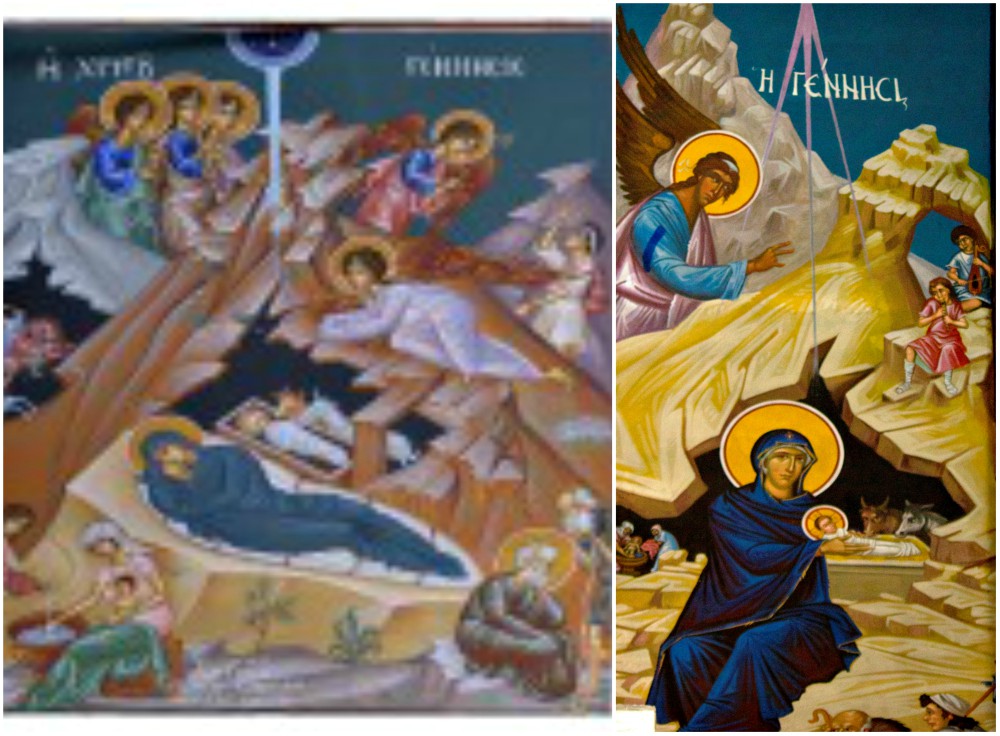

Kontoglou was a reference point for the young hagiographers of his time who followed their teacher’s standards. One of them was Cretan iconographer Stylianos Kartakis (1912-1988), from Placalon, Kissamos, who painted in genuine Byzantine style[14]. Kartakis’ foremost work was the Byzantine frescoes adorning many churches in Crete and all over Greece, such as the Nativity of Jesus Christ fresco at the Church of St. Nectarius in Chania. Kartakis’s painting is characterised by the elaborate design, color harmonies and the contrasts of warm and cold tones.

In his fresco, Kartakis follows Kontoglou’s iconographic style and the Byzantine iconographic tradition in depicting the Nativity. In the middle of the composition lies the triangular cave surrounded by “crystal rocks”. In its black opening, symbolising the darkness of the pre-Christian world, is the manger with the newborn Jesus glowing in his white swaddling clothes. An ox and a horse warm him with their breath, while the Virgin Mary lies down next to the Divine Infant. Above them, at the top of the cave, a chorus of angels sing praises rejoicing for the coming of the Messiah, while on the left another angel carries the joyous message to the shepherds. At the bottom, Joseph is immersed in his thoughts, talking to an elderly shepherd. Two women prepare to bathe the infant Jesus in a baptismal font. On the left of the composition, in the mountains, the three Magi could be seen on horseback on their way to worship the divine infant.

Left: Stylianos Kartakis, Nativity of Jesus Christ, Right: Giorgos Kounalis, Nativity

Left: Stylianos Kartakis, Nativity of Jesus Christ, Right: Giorgos Kounalis, Nativity

Kontoglou’s assistant was the painter and iconographer Giorgos Kounalis, a native of Neapolis in Lassithi, Crete. Born in 1935, he lived and worked in Chania, and painted in the Byzantine style. He studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts and at the Frescoes and Icon Workshop. He studied Byzantine Hagiography in Mystras and Mount Athos. The experience he gained while working as an assistant to Fotis Kontoglou (1963-1964) was decisive.

Kontoglou’s influence on Kounalis is evident in the painting of forms. Stylistically, Kounalis shapes his forms with dark patterns, while with white light strokes he illuminates facial aspects. In the photomorphic Byzantine style, successive layers gradually develop into lighter tones with the addition of white color. Garments are shaped with tonal gradations of the same color, and folds are slightly emphasised. The children welcoming with music the coming of the Messiah are a modern element in iconography.

Left: Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity, Right: Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity (detail)

Left: Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity, Right: Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity (detail)

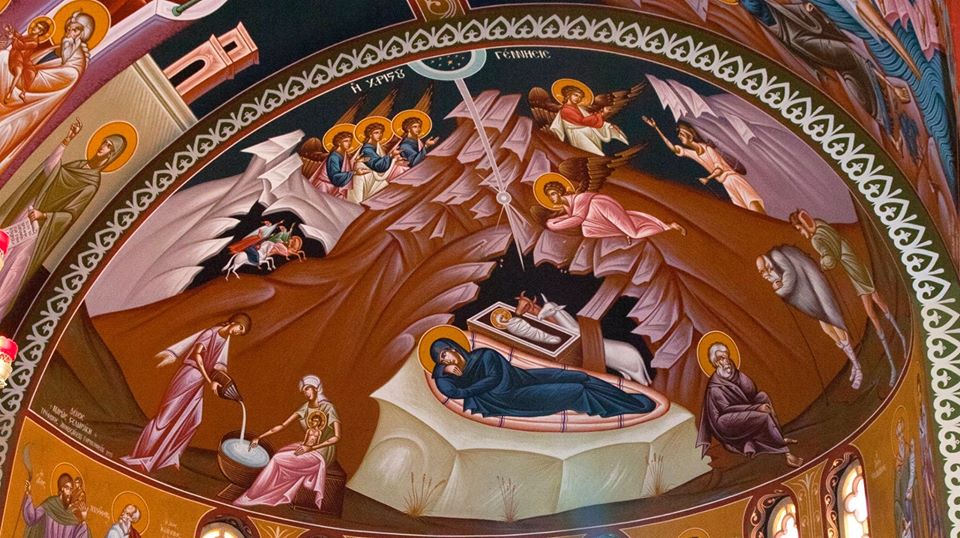

And we conclude the overview of indigenous hagiography with a brief reference to contemporary painter-hagiographer Nikos Giannakakis, from Gramvousa, Kissamos. Giannakakis was an apprentice to Kartakis and worked with him on the painting of St. Minas Church, in Heraklion (1968). He studied painting and Byzantine hagiography at the School of Fine Arts and mosaics in Florence. In his hagiographies, he harmoniously blends the characteristics of the Cretan school with traditional Byzantine art.

Giannakakis maintains a creative relationship with Byzantine tradition avoiding its imitative reproduction. As we see in his frescoes depicting the Nativity, the peculiarity in his hagiographic style is primarily due to the intense expressiveness of both gaze and movements of the sacred figures as well as the use of color as a basic expressive mean of conveying feelings[15]. Giannakakis gives a personal quality to Orthodox religious painting. He creates a vivid ecclesiastical art that paves the way for renewal. He has worked in many churches in Greece as well as Catholic churches in Italy and France. He has been honored in Greece and internationally. His frescoes are found in many churches of the city and prefecture of Chania.

Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity

Nikos Giannakakis, Nativity

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to review the aesthetic character of religious painting in Chania through an overview of depictions of the Nativity scene. In conclusion, we find that indigenous religious art is a living means of expressing the ecclesiastical experience and is thus influenced and shaped by the impact of the wider historical context and developments in the field of arts.

The progressive integration of western elements in Orthodox iconography began in mid 15th century with the Cretan School of Hagiography. The incorporation of naturalistic elements into religious painting continued with Nazarene art which prevailed in Crete as well. In Chania in particular, the “Nazarene” style of indigenous hagiographers formed a very important and creative part of local ecclesiastical art. Thanks to its technical excellence and its idealistic style, it was much loved by the people. In the 1930s, Kontoglou began a fierce struggle for the return of religious art to the sources of Byzantine tradition and to post-Byzantine stylistic elements. Byzantine art was considered to be the only one capable of expressing Orthodox theology and creed. Younger Cretan hagiographers followed Kontoglou’s path and continue to follow it in an effort to preserve and renew the post-Byzantine tradition.

The Nativity scenes in icons and frescoes presented in this study provide evidence of the high aesthetics of indigenous hagiographers, elaborately chart the development of Orthodox painting in Chania and allow the faithful to perceive religious art both as an experience of worship and aesthetics.

Translation by Marianna Varvarrigou & Magda Hatzopoulou (Intro image: Left: Theodoros Poulakis, Epi Si herei, Right: Theodoros Poulakis, Epi Si herei [detail])

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Christmas in Modern Greek painting; Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Erotokritos’ intercultural substance and influence on Greek painting

[1] Paliouras, D. “Painting in Handakas from 1550-1600”. Treasures, Institute of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies, Volume 10, 1973, pp. 101 -123.

[2]See e.g. the icon of Our Lady of Passion at Rethymnon Cathedral, by unknown iconographer.

[3]Alevizou, Deniz-Chloe, The Crete of Artists: 19th 20th century Hagiography – Painting – Sculpture, ed. Tedmakis, Heraklion, 2010, pp. 20.”Famous Cretan painters have been painting” in the naturale since the 16th century. “Designation means imitation of nature or even oil painting technique.”

[4]The picture Epi Si herei reads: “Theodorou Poulakis, from Kydonia, of the famous island of Crete”.

[5] See Lydakis St., Dictionary of Greek painters and engravers, ed. Melissa, Athens, 1976, p.362.

[6] Iconographers from Chania influenced by the the Nazarene Western style included Xenophon Papangelakis, Michael Papadakis, Manolis Theodosakis, Nikolaos Vlachakis, Stylianos Perrakis and Georgios Polakis. They adopted academism in their work adopted, in the context of the so-called “improvement and correction” of Byzantine art.

[7] See Alevizou (2010), p.210.

[8] “Religious Issues in Modern Greek Painting, 1900-1940”, Doctoral Thesis, Thessaloniki, 1984, p.24. See also Alevizou, (2010), p.60.

[9] Biographical and other details about the iconographer S. Perrakis, see Alevizou, (2010), p213.

[10] Biographical and other information on iconographer G. Polakis, see Alevizou, (2010), p.187.

[11] See Lydakis St. (1976), p.358.

[12] See Lydakis, (1976), p.187.

[13] For the codification of the elements of Byzantine Iconography and in particular for the technique of preformations, see. Kontoglou Fotis, “Expression of Orthodox Iconography”, vol. A, ed. Papadimitriou, 2000, p. 47.

[14] Biographicaland other details about iconographer Kartakis, see Lydakis S., (1976), 167 and Alevizou, (2010), p.265 – 268.

[15] Philis Yiannis, Nikos Giannakakis: I am a Hagiographer, Chania Regional Unit, Chania, 2015, p. 47.

TAGS: ARTS | HERITAGE | MODERN GREEK STUDIES