No other painter of Greek descent shares the renown of Domenikos Theotokopoulos, universally known as “El Greco”. Evidently classic and irrefutably modern, his visionary work is continuously rediscovered and reevaluated as a paradigm of genius, originality and innovation.

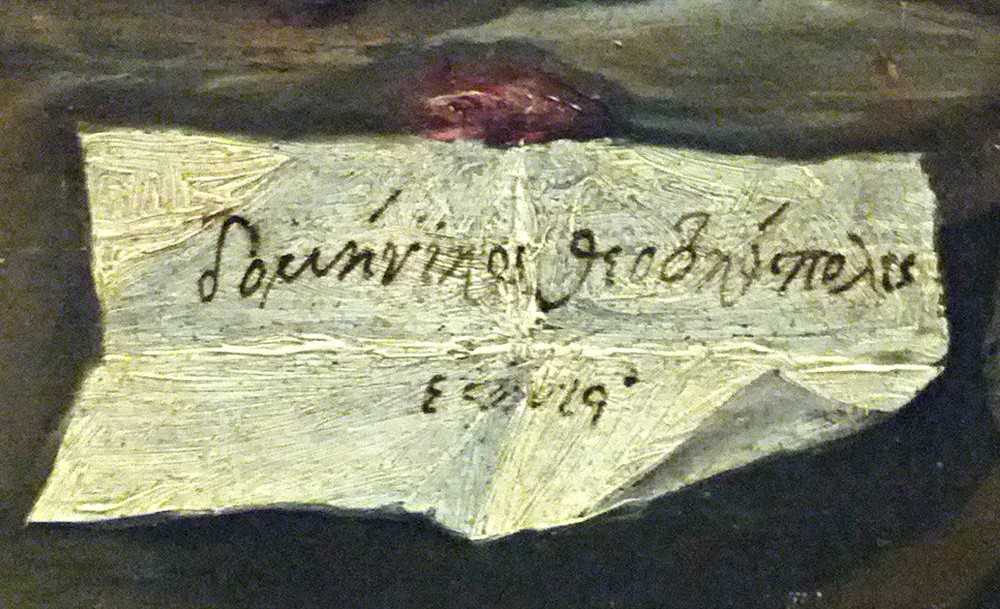

Although often cited as a Spaniard, and even considered by some to be a quintessential Spanish artist, Theotokopoulos was born in Crete, where he spent at least the first two decades of his life and received his original artistic training as an icon painter. He never rejected his origins, and signed his works in his full name in Greek.

It was probably in Italy that he began to be referred to as il Greco (the Greek), most likely by people who found his long family name difficult to remember or pronounce. Later, in Spain, he would also be called “the Greek”, i.e. el Griego. It was only posthumously that the byname “El Greco” really took hold; its eclectic quality indeed reflects the plurality of his identity: a Spanish article and an Italian adjective are used to designate someone as “the Greek”.

Left: Dormition of the Virgin, before 1567, Church of the Dormition of the Virgin in Ermoupolis, Syros; Right: Portrait of a Man (presumed self-portrait of El Greco), c. 1595–1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Left: Dormition of the Virgin, before 1567, Church of the Dormition of the Virgin in Ermoupolis, Syros; Right: Portrait of a Man (presumed self-portrait of El Greco), c. 1595–1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Crete – The Byzantine years

Domenikos Theotokopoulos was born on 1 October 1541 in the Kingdom of Candia, i.e. Crete, then a colony of the Republic of Venice. Due to its close ties with Italy, the heart of the Renaissance –at a time when the rest of Greece was under Ottoman rule– Crete had by then evolved into the most important centre of post-Byzantine art and culture. This period is often referred to as the “Cretan Renaissance”.

The Cretan School of painting, which had developed since the 15th century, had produced many important iconographers, and young Domenikos would also follow that tradition, making a name for himself as an icon painter and presumably operating his own workshop by his early twenties (in documents from that time he is referred to as “a Master”).

The few icons by his hand that have survived from this period, such as The Dormition of the Virgin, combine post-Byzantine and Italian stylistic and iconographic elements. This incorporation of Western elements in “Greek style” icons is probably the most characteristic trait of the Cretan School, and can also be seen in the works of many other artists, such as Michael Damaskenos.

The Adoration of the Magi, 1565–1567, Benaki Museum, Athens

The Adoration of the Magi, 1565–1567, Benaki Museum, Athens

Italy – A turn to the West

Given Crete’s close connection with Venice in that period, it was little wonder that a promising painter, such as the young Domenikos, left the Kingdom of Candia for the Italian metropolis, like other Cretan artists before him. The exact date of his arrival in Venice is unknown, but it is generally believed he was living there by 1567. According to the renowned Renaissance illuminator Giulio Clovio, Theotokopoulos was a disciple of the great Titian and “a rare talent”. In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he also spent a few years, operating his own workshop, before eventually leaving for Spain.

Theotokopoulos’s style was transformed as a result of his Italian apprenticeship, with a Western European style taking the place of his previous post-Byzantine one. His works exhibit a strong influence from the Venetian Renaissance style, especially in the use of rich colours, which is reminiscent of Titian’s works; the extended use of perspective and multi-figure compositions also demonstrate the strong impact of the great masters, such as Michelangelo and Raphael, whom he also considered as models.

These features are apparent in Christ Healing the Blind, a painting he created in the 1570s, where one can also already identify elements of Mannerism, especially the elongation of many of the human forms – a trait which would go on to become arguably the most distinctive attribute of his art. In his portraits of Giulio Clovio and Vincenzo Anastagi his extraordinary gift as a portraitist is also already evident.

Christ Healing the Blind, c. 1570, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Christ Healing the Blind, c. 1570, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Spain – Artistic maturity

At some point in 1576–77 Theotokopoulos would move to the Spanish capital, ostensibly in the hope of securing a royal patronage from King Philip II, who was at the time building the majestic Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. He eventually settled in the nearby Toledo, where he would remain for the rest of his life. At the time, the city was considered the “religious capital” of Spain, as the famous Toledo Cathedral was the seat of the Primatial Archdiocese of Spain.

In Toledo, Theotokopoulos began to form a circle of friends and patrons, including brothers Luis and Diego de Castilla, Spanish clerics with whom he had been probably acquainted in Italy; the latter served as dean of Toledo Cathedral, and hired the artist for important commissions. These included the altarpiece and the two lateral altars in the conventual church of the Santo Domingo el Antiguo Monastery –Greco’s first major commission– and also the renowned Disrobing of Christ (El Expolio) for the High Altar of the sacristy of the Toledo Cathedral. In these works, one can already identify the traits that went on to form the painter’s characteristic style.

El Greco even secured two commissions by Philip II in the late 1570s: the Adoration of the Holy Name of Jesus (also known as La Gloria, The Dream of Philip II or Allegory of the Holy League, 1577–1579) and The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice (1580–1582). However, the monarch was not satisfied with either of the two paintings, ending any hopes of royal patronage for the artist.

Left: The Disrobing of Christ (El Expolio), 1577–1579, Sacristy of Toledo Cathedral; Right: The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice, 1580–1582, Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid

Left: The Disrobing of Christ (El Expolio), 1577–1579, Sacristy of Toledo Cathedral; Right: The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice, 1580–1582, Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid

The painter thus remained in Toledo, where he was very well received. Classical scholar Antonio de Covarrubias, cleric and historian Don Pedro de Salazar de Mendoza, influential poet Luis de Góngora y Argote and preacher and poet Hortensio Félix Paravicino were also among his entourage.

In Toledo, Theotokopoulos had a son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, born in 1578. His mother was Jerónima de Las Cuevas, the artist’s companion, whom he is believed to have never married for unknown reasons. From 1585 onwards, he resided in the large, late-medieval palace belonging to the Marquis de Villena, which also housed his workshop.

In 1586 he obtained the commission for his most celebrated work, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, for the church of Santo Tomé (where the Count portrayed in the painting was buried), which gained immediate recognition and acclaim. In the following years, he received several major commissions, and his workshop created pictorial and sculptural ensembles for a variety of religious institutions.

In early 1614, Theotokopoulos fell seriously ill and died on 7 April, at the age of 73. He was buried in the Church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, which also houses the altarpiece that was his first commission in Toledo. His son, Jorge Manuel, initially followed in his footsteps, but later focused on architecture; in 1625, he became the Master Builder, sculptor and architect for the Toledo Cathedral.

Left: View of Toledo, c. 1596–1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Right: Opening of the Fifth Seal, 1608–1614, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Left: View of Toledo, c. 1596–1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Right: Opening of the Fifth Seal, 1608–1614, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Unique style

In a sonnet dedicated to El Greco after his death, the Trinitarian monk Hortensio Félix Paravicino, a close friend of his, compared him to the legendary Hellenistic painter Apelles and wrote that “Crete gave him life and his paintbrushes, Toledo [gave him] a better homeland, where he begins to reach eternity through death”.

It was indeed in Toledo that Theotokopoulos’s art fully transformed into what has come to be known as El Greco’s distinctive style. His tendency to elongate the human figure –in a way reminiscent of Michelangelo, evincing the strong influence of Mannerism– along with the daring use of vibrant, contrasting colours –evocative of the Venetian palette– are arguably the most striking features of his works. These traits are taken to the extreme in his later works, where the twisting, elongated forms defy the laws of nature and appear almost dematerialised, as can be seen in paintings like the Opening of the Fifth Seal (also known as The Vision of Saint John, 1608–1614) and Laocoön (1610–1614).

Laocoön, 1610–1614, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Laocoön, 1610–1614, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

El Greco was also distinguished as a remarkable portraitist, known not only for accurately rendering the sitter’s features, but also for the lifelike energy of the figures and for effectively capturing the subject’s character. Among his most famous portraits are those of Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara (1600) and of his personal friend Fray Felix Hortensio Paravicino (1609). Again in a sonnet, inspired by his own portrait, Paravicino wrote that the work of the “Divine Greek” surpassed nature, and that his own soul stood perplexed, unable to decide whether it should dwell is his own body or in the painting.

The artist never renounced his Greek heritage, and usually signed his paintings with his full name in Greek letters, often adding “Κρης” (Cretan); however, by the end, his personal style had evolved into a completely different direction compared to his early work in Crete. As art historian Keith Christiansen of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art writes, “no other great Western artist moved mentally—as El Greco did—from the flat symbolic world of Byzantine icons to the world-embracing, humanistic vision of Renaissance painting, and then on to a predominantly conceptual kind of art”.

Harold Wethey, prominent art historian and El Greco scholar, noted that, although the artist was Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, his deep immersion in Spain’s religious environment turned him into “the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism”. He notes, however, that “because of the combination of these three cultures, he developed into an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school but is a lonely genius of unprecedented emotional power and imagination”.

Left: Portrait of the Artist’s Son Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, 1600–1605, Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla; Right: Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, 1609, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Left: Portrait of the Artist’s Son Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli, 1600–1605, Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla; Right: Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, 1609, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Influence & legacy – A universal artist

Despite being widely –though not universally– appreciated in his own time, especially in Toledo, Theotokopoulos was generally overlooked by the following generations, as Mannerism fell out of fashion. His style did not appeal to Baroque artists and art commentators, who perceived his original compositions and elongated figures as eccentric or even ridiculous.

A rediscovery of El Greco’s work began in the early 19th century, thanks to the Spanish gallery of king Louis-Philippe at the Louvre and the rise of the Romantic movement. The Romantics, excited by the fantastic and the extreme, were fascinated by El Greco, especially by what famous writer Théophile Gautier described as “a depraved energy, an unhealthy strength that betrays the great painter and the madness of genius”. In 1867, art critic Paul Lefort would proclaim Theotokopoulos the founder of “the Spanish School”.

However, it wasn’t until the early 20th century that a reappraisal of El Greco’s work truly took place, thanks in great part to art historians Manuel Bartolomé Cossío and Julius Meier-Graefe. The latter wrote about Theotokopoulos that “all the generations that follow after him live in his realm.” In 1910 the El Greco Museum was founded in Toledo. English painter and critic Roger Fry described El Greco in 1920 as ”an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way”.

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–1588, Church of Santo Tomé

The dramatic, transcendental nature of his paintings and the subjective perception of reality in El Greco’s work give it a radical quality that deeply affected and inspired modernist artists. Several art historians and critics have identified a direct connection between Theotokopoulos and Paul Cézanne, Post-Impressionist and precursor of Cubism.

Another artist (and pioneer of Cubism) whose works demonstrate a strong and continuous influence from El Greco is Pablo Picasso; this can be seen not only in his series of “paraphrases” (where he pays tribute to a number of earlier artists) but also in some of his most famous compositions, such as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), as well as in statements made by the famous Catalan artist.

As art historian Ephi Foundoulaki points out, since its rediscovery by the Romantics, El Greco’s work “became the precious tool of a new approach to modern art, acting as a ‘revelatory agent’” for Impressionists, Symbolists, Modernists and Expressionists. As she notes, since the 20th century, his work “complex, diverse, singular, and contradictory, becomes open to various interpretations. The deformation of the human form, […] the contrasted values of colour and form […], the strong rhythm of broken lines, are some of the formal elements that the modern painters have detected in his work and have often adopted, considering [him] a ‘modern’ painter and inviting him to be part of the discussion concerning the art of their time. That is how the universality of El Greco’s art is being shaped”.

Signature of Domenikos Theotokopoulos, reading “Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος εποίη” [Domenikos Theotokopoulos made this] (detail from St. Andrew and St. Francis), 1595-1598, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Signature of Domenikos Theotokopoulos, reading “Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος εποίη” [Domenikos Theotokopoulos made this] (detail from St. Andrew and St. Francis), 1595-1598, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Nefeli Mosaidi (Intro image: The Burial of the Count of Orgaz [detail], 1586–1588, Church of Santo Tomé)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Art historian Alexandra Kouroutaki on Erotokritos’ intercultural substance and influence on Greek painting; Discover the National Gallery of Athens

TAGS: GLOBAL GREEKS