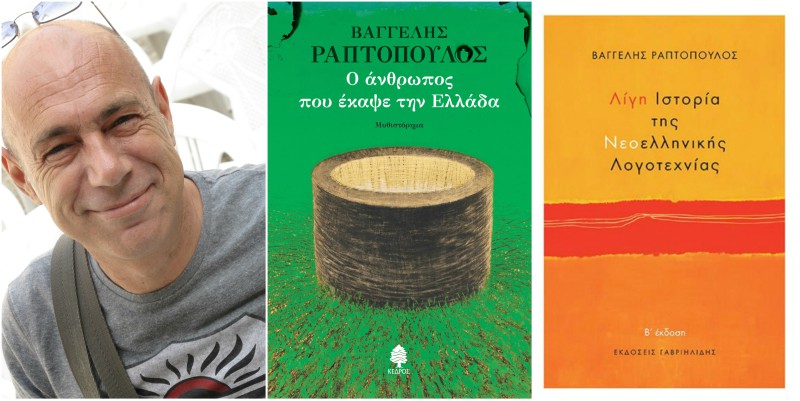

Vangelis Raptopoulos is one of Greece’s most notable contemporary writers of fiction. He published his first book, a short story collection, to wide acclaim at twenty years of age, and has since been a steady presence in Greek letters, with over twenty-five books. He mainly writes novels and short stories, but has also published collections of essays and articles. With studies in pedagogy and journalism, Raptopoulos has also worked as a publisher’s reader and script reader, as well as a radio broadcaster, and has also been a regular contributor to many newspapers and magazines of wide circulation.

Raptopoulos has taught creative writing in various colleges and institutions; his novel The cicadas (1985) has been translated in English, and The Incredible Story of Pope Joan (2000) has been translated into Italian. His first two books have been adapted for television, while his 1993 novel The bachelor has been adapted into an award-winning film by acclaimed Greek director Nikos Panayotopoulos. Raptopoulos has become known for his personal style of writing, often creating a mixture of tragedy and comedy, deliberately verging on parody. This is particularly obvious in his latest novel, The man who burned down Greece, an alternative history book inspired by Greece’s financial crisis, which has already been praised as one of his best.

The book’s protagonist is Dimitris Apostolakis, whom the author himself describes as a “modern day Don Quixote from Greece”. Born with the rare gift of pyrokinesis, the hero often sets fires unintentionally, usually in stressful or unsettling situations; for him, it is a deeply soothing experience yet one with a frightful outcome. During the Greek financial crisis, Apostolakis loses his job and eventually abandons his family to go live on the streets.

Caught in a maelstrom of misery, resentment and, in the end, fury, the hero -who has now managed to master his own powers- decides to go on a mission, targeting buildings he views as symbols of capitalist injustice; he sets a number of destructive fires that trigger massive popular revolts in Athens and all major Greek cities, resulting in extensive damages and multiple deaths – including his own. Vangelis Raptopoulos spoke* to Greek News Agenda about his latest novel, his thoughts on contemporary Greek reality and fiction, and the symbolic theme of pyrokinesis.

Your book is written in epistolary form – where did this idea come from? In fact, it shares many common traits with Dracula, one of the most widely acclaimed novels of the horror genre, which is also directly referenced in your book: it predominantly consists of diary entries but also letters (e-mails), newspaper clippings, messages, transcripts, etc. Was Dracula a strong inspiration for you?

With regard to the novel’s form, or rather its structure, my initial inspiration came from the rather unknown in Greece psychological thriller What She Left, by first-time novelist T.R. Richmond. It is a contemporary epistolary novel, a patchwork of Facebook posts, forum comments, tweets, emails, text messages etc. This book further reminded me of another celebrated debut novel, this time by one of my favourite authors: Stephen King’s Carrie, which in turn seems inspired by Stoker’s Dracula – and not just with regard to its structure. Dracula, probably the most compelling novel I have ever read and one of horror fiction’s quintessential works (together with Shelley’s Frankenstein and Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), manages to make a convincing case for one of speculative fiction’s most incredible subject matters, thanks in great part to its composite, fragmented structure. King uses a similar structure and technique to convince us of the existence of his telekinetic heroine, I use it to make my pyrokinetic hero’s existence convincing.

Photo: Urs Voegeli

Photo: Urs Voegeli

Generally speaking, you do not attempt to mask your influences. Books, films, songs, mottos that are likely to spring to the one’s mind while reading your novel are often referenced by the characters. Do you intentionally use these direct allusions, as does Brian De Palma for example, famous for recreating scenes or plots from Hitchcock or Eisenstein in his films?

This choice is as deliberate as is anything resulting from one’s disposition or temperament. In other words, there are writers who are secretive and others who are very open when it comes to their sources of inspiration, but I guess no one gets to choose which will be his type. This streak in me was sharpened from one point onward, as I incorporated many pulp elements in my work in order to more profoundly express not just myself, but also our time. A time bereft of values, ideals and a slave to money; a time of which we cannot talk by means of the high art of the past, making it almost imperative that we approach it through popular genres, starting from crime and horror fiction all the way to pornography. These choices have put me in the line of fire of literary critics and the literary status quo, so I found it necessary to inform my readers about my influences and my intentions, which the critics either overlooked or were simply unaware of.

One the novel’s central themes is the growing number of homeless people in Greece, as well as their social status. In the hero’s first-person narration you include some very disturbing details about life on the streets. Where did you draw such detailed knowledge about the homeless’ living conditions?

Some of the homeless characters portrayed in the novel are based on news stories from the media, as I mention in my postface at the end of the book. Other details I drew from my own keen observations of the homeless in the centre of Athens, mainly between 2012 and 2014. Nonetheless, I would say that, as always, most of the work was done by my imagination. The same more or less happened with Loula (when readers consistently asked how I knew so much about female orgasm) and Lesbian (with questions this time focusing on my knowledge of homosexuality), just to mention two blatant examples. A novelist observes his surroundings and then imagines the rest, that’s how it always has been and always will. A novel in Greek is very aptly called mythistorima, combining the words “myth” and “history”: it is part invention, a tale, and part history, reality. As for the homeless, they constitute the crux not just of this novel, but also of the financial crisis. In a country where owner occupancy is still the rule (and where as a rule all institutions, save that of the family, are imported and impaired) there is no greater misfortune than to not have “a roof over one’s head”. Finally, I think that, if family wasn’t as important as it is in Greece, then the crisis wouldn’t have just increased the number of the homeless, it would have literally wiped us out.

In your postface you note that a major inspiration for your book was the (Greek) Left’s fixation with social revolt, as well as “the obsession of almost all of today’s Greeks with wanting to see the world burn”. Following the hero’s path into utter deprivation, the reader empathises with his eventual catastrophic outburst; can we assume that you partly justify his destructive urge – and, in particular, his desire for catharsis by fire? Or do you agree more with the fictional commentator’s claims that no substantial change can come from destruction?

Surprisingly, I agree with both these views. After all, this is one of the privileges of writing a novel; it gives you the space to elaborate on opposing and contradictory opinions (something strictly forbidden in real life by threat of being labeled schizophrenic, at best). Our lives in this tiny corner of the globe can often become unbearable, unlivable actually, due to certain, apparently systemic, social defects and afflictions that plague us. Especially in these times, Greece can be surrealistically dysfunctional and wretched, whilst the prevalent unfairness, favouritism and apathy can often drive you to the end of your rope. So leveling everything to the ground may seem like the only solution and way to catharsis. On the other hand, I don’t believe there’s anyone in Greece who believes that this would actually change anything and bring deliverance. If you just think about it, my novel falls into the genre of political fiction or alternative history, and yet it chronicles an imaginary, invented uprising, after which everything falls back to normal, as if nothing had happened; this is quite original. In novels of this category the hero travels back in time to, say, kill Hitler’s parents and spare the world of WWII. In my novel, we pant and gasp all over again, like Sisyphus, rolling the same boulder up the hill, no matter what or how much we’ve tried to change our fate. As if we are doomed to perpetually bear our burdens, whether we fight back individually and collectively or not.

Before embarking on his ultimate arson spree, the hero, Apostolakis, gets a shave and haircut and takes a long hot shower, bringing to mind the Spartan custom before battle. Regardless of the final outcome of his rebellious mission, do you think of Apostolakis more as a fighter, like the anarchist organisations view him, or as a madman, as his own daughter describes him? Or, possibly, as a part of you which you are struggling to leave behind, as does Apostolakis’ widow, who wavers between her guilt of betrayal and her desire for a new life?

Before embarking on his ultimate arson spree, the hero, Apostolakis, gets a shave and haircut and takes a long hot shower, bringing to mind the Spartan custom before battle. Regardless of the final outcome of his rebellious mission, do you think of Apostolakis more as a fighter, like the anarchist organisations view him, or as a madman, as his own daughter describes him? Or, possibly, as a part of you which you are struggling to leave behind, as does Apostolakis’ widow, who wavers between her guilt of betrayal and her desire for a new life?

Once again, I think that he is in fact all of those things. And above all, I believe my hero is still a part of me that I myself have mocked, scoffed and scorned as much as I could. However, if I had to choose just one answer, the version I would point to would be that of a comic yet tragic hero, a noble madman, a naive rebel, a romantic radical. Dimitris Apostolakis is a modern-day, Greek-born, Don Quixote, like any self-respecting hero in a novel since the genre itself was introduced by Cervantes. Just as the other two heroes, his wife, Lena Apostolaki, and their friend, Giorgos Theodoridis, can’t help but exemplify a dual, two-headed, Sancho Panza. Maybe this is inevitable and there is no other possibility for human existence. Not to mention that, in fact, each of us incorporates both sides, Don Quixote and Panza, otherwise we are not humans, but monsters.

Mourning is another pivotal theme in the novel; the hero mourns for his parents as well as for his victims, while his own loss (made known to the reader early in the book) is mourned by his loved ones. In your postface you claim that what triggered the idea for this story was the loss of your father. You also say that pyrokinesis is the ideal metaphor for the process of writing; does this have to do with a book’s ability to spark thoughts like flames, or rather with writing as a soothing energy discharge that relieves one’s pain, reminiscent of the alleviating effect that the fire-starting occurrences have on the hero’s psychology?

It is true that mourning is a pivotal theme in the novel (although this could sound misleading since this isn’t an elegiac novel but rather a black comedy); especially mourning, one could even say, for the absence of a massive uprising, a reaction against the crisis that has crushed us all these years. And, of course, mourning for the human losses caused by the crisis. As for the writing metaphor, I believe that almost all paranormal abilities are ideal for this purpose. Especially telekinesis, since the writer essentially controls the heroes with his mind, and we have the feeling that this psychic power has been invented just to express the creativeness of storytelling. The same is more or less true for pyrokinesis, and other such paranormal powers as well. I refer to the fact that these powers are obviously fictional (as are literary heroes and their actions) as well as the fact that the creator, like a small god with supernatural powers, controls his brainchildren like a puppeteer. What’s good about metaphors is that they are open to countless interpretations which are all legitimate. For instance, I had never thought of “a book’s ability to spark thoughts like flames”, as you said, but it really befits pyrokinesis as a metaphor for writing. And, of course, this is even truer for your other suggestion, i.e., what better way to describe writing and creativeness in general than as a “soothing energy discharge that relieves one’s pain”? What’s even better however is that any other interpretation you think of for a metaphor is also true. In other words, welcome to the infinite, perpetually expanding, and thus ever uncharted realm of metaphors and their interpretations that compose and comprise the unchildlike game that is fiction.

In your novel you reference Stephen King, especially in relation to his book Firestarter, however by the end there are strong allusions to Carrie: we empathise with the tormented hero (like the bullied and domestically abused Carrie) using psychic powers to wreak havoc terrorizing the just and the unjust, and leading to his own demise. However, the story ends with the ominous revelation that those same powers have manifested in someone else. Is this a warning: “As long as injustice prevails, there may well be another fierce reaction”?

It is obviously a warning on the eternal perpetuation of events, on the endless rebirth of the notion of rebellion against authority. And, above all, it is another turn of the screw in the black comedy that is my book, as are our lives. It is also a sticking out of the tongue in front of a mirror, against even my own self, a taunting, sarcastic sticking out of the tongue by the subconscious, irrational part of me against the sensible, Apollonian, logical and reasonable part of me. This latter part of me, of each of us maybe, is the part that thinks of the future reappearance of those pyrokinetic powers in the population as something ominous. On the contrary, our fiendish, Dionysian and rebellious part is absolutely delighted at the prospect, since this would actually be its own resurfacing from the dark vaults of the subconscious. So the end of the novel tries to warn rational readers and citizens that they shouldn’t rest assured, evil lurks, sneaks and creeps, ready to rise again from its ashes like a phoenix, at any time.

Photo: Argyris Giaitzoglou

Photo: Argyris Giaitzoglou

Having just released an epistolary novel, your next project is a publication of your written correspondence with your mentor and close friend, celebrated writer Menis Koumandareas (1931-2014). How long did this correspondence last? What can the readers learn about both of you through this volume, and what insights would you wish them to gather from it?

My correspondence with Menis Koumandareas began in 1979, before I even published my first book, and continued until 2001, the time of the publication of my eleventh book, the short novel Black wedding. Yet, most of it comes from a period of barely over a year – 1981, when I lived in Sweden. The book’s title will be Confession and tutelage – because this is exactly what we did through those letters; in fact this was a mutual confession (although his reached deeper, due to his age and experience) and a mutual tutelage (because, even though I was the novice, the apprentice, Menis possessed the rare gift of not being patronising, and of constantly trying to learn, even from a beginner like me). In addition to a preface, written by me, the book will also feature an essay by Antigone Vlavianou, an academic who, by good fortune, was also a friend of Menis. Readers will know more about Menis through this book, since at the time he was one of our most prominent prose writers in his prime. As for myself, I think it’s obvious in the correspondence that I was already resolved on following the literary path I eventually took; or, to say it differently, that even when taking his first steps, a prose writer is more or less already shaped. However, what I really hope the readers will get from this publication is a feeling that its first two readers -my wife, Stavroula Papaspyrou, and Antigone Vlavianou- told me they got: they were moved by this 400-page volume, now under publication, because, apart from its literary value, it never ceases to be a deeply emotional book, bringing a male friendship to life.

You have also recently released a reprint of your book A bit of Modern Greek Literature History, featuring 39 interviews and essays on 82 contemporary Greek writers -from established figures such as Andreas Frangias and Thanasis Valtinos, to representatives of the younger generation, such as Vangelis Hatziyannidis, Angela Dimitrakaki and Sophia Nikolaidou– published between 1985-2005. Revisiting those texts now, with the benefit of hindsight, what is your assessment of that period’s literary production? Do you subscribe to the often-repeated belief that Greek fiction is overshadowed by Greek poetry, taking into account the latter’s broader international recognition thanks to our two Nobel Prize winners in Literature?

Fiction in Greece is no longer overshadowed by poetry. Not because contemporary poetry is inferior to that of the past, but because it has been marginalised in our unpoetic times. Especially lyric poetry, which had brought both local and international fame to our literary production in the recent past. I explicitly express these thoughts in an essay on the death of Odysseas Elytis, featured in this volume. The problem with prose produced in our times is that readers and good literature seem to have divorced: On the one hand, readers have developed a consumerist approach, and only look for escapist fiction of no real value, which in Greece means either historical novels or romances, whilst on the other, novelists of a certain calibre often flounder between experimental writing exercises and obsolete viewpoints or choice of subject. The result is that important works of fiction do not reach their natural readership, since readers are faced daily with piles of books that are trivial or just pointless. The last essay of my book bears the ambiguous title “The royal path”. When I began publishing my works some fourty years ago, the writer revered by the literary world of the time was Kostas Tachtsis, who had published only a few books, while the prolific Vassilis Vassilikos, who remains one of our most translated writers, was sneered at. My colleagues praised the first for his aristocratic approach to writing, and dismissed the latter as perfunctory. As things stand, it is obvious that life followed the path of the latter, hence the wordplay (vassilikos means royal in Greek); Tachtsis as a paradigm seems to be definitely a thing of the past.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi (Opening photo by Katerina Raptopoulou)

Read also on Reading Greece: Thanasis Valtinos, A Highlander at the Academy of Athens; Vangelis Hatziyannidis: “Writing for an opera was like a puzzle I really enjoyed”; Angela Dimitrakaki on Subjectivity in Global Landscapes; Sophia Nikolaidou on the Representation of Greece’s Political Past in Contemporary Literature