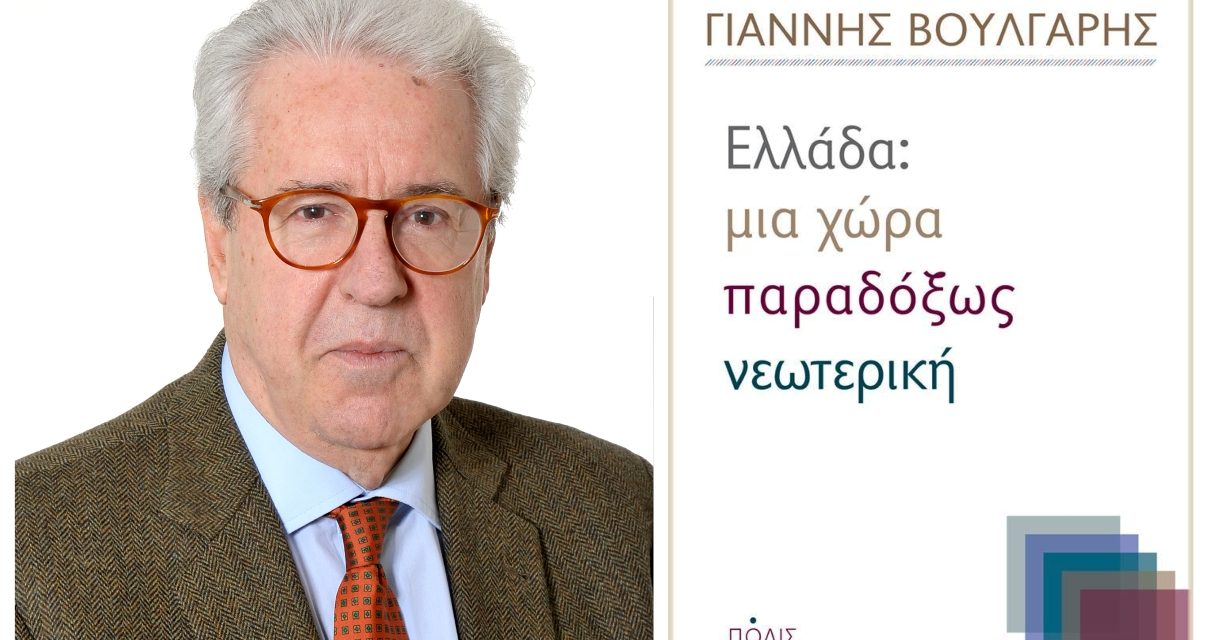

Yiannis Voulgaris is Emeritus Professor of Political Sociology at Panteion University. His scientific and research work is mainly focused on the fields of political science, modern Greek politics and the theory of globalization. Among his publications are the books “Greece: A Paradoxically Modern Country” (2019), “Post-Metapolitefsi Greece 1974-2009”, which has also been translated to German (‘Politische Geschichte Griechenlands Parteien, Institutionen und politische Kultur vom Fall der Militärdiktatur bis zur Wirtschaftskrise‘) and “Greece from the Metapolitefsi to Globalization”. His essays and articles focus on issues of democracy, the State and civil society, globalization and historical sociology. His books and articles have been published in Italian, German and English. Voulgaris was a founding member of the Archives of Modern Social History (ASKI), has served as the Director of the Centre for Political Research at Panteion University, and recently as a member of the Greece 2021 National Committee. He contributes articles to national media publications on a regular basis.

Professor Voulgaris spoke to Rethinking Greece* on modern Greece as a success story; the Greek state’s crucial contribution to the modernization of the country; the long-lasting consequences of the “twin birth” of the Modern Greek State as a democracy; how the national goals that arose from our quest to ‘catch up’ with ‘Europe’ have shaped today’s Greece; the reaffirmation of the country’s European orientation as the “conclusion” reached by the vast majority of citizens that experienced the crisis; the defining role of Geopolitics and the autonomy of politics as macro-historical features of our national evolution, and finally, how Greece has always been exposed to the sharp turns of History and what this means for the goals the country needs to set for the future.

Earlier narratives that focus on modernization in Greece are characterized by a relatively pessimistic undertone. A more recent trend in Greek historiography argues that the modern Greek state has been a success story. What is your view on the issue?

Indeed, the “national narrative”, during the post-war and early post-Metapolitefsi period has been formulated in negative terms. Greece was a case of backwardness, underdevelopment, dependence, or, to put it mildly, a delayed, distorted and incomplete modernization. Historical conditions can explain this negative assessment. Greece was the only country in Western Europe that experienced a Civil War as well as a dictatorship in the post-war period. It thus stood out like a negative exception to the “European rule”, that is, to the standard established by developed countries, and the various “schools of thought” had a different interpretation as to the causes of this backwardness. Marxists insisted on economic causes and dependence, liberals on cultural causes and the nationalists-conservatives on the injustices that the country suffered occasionally “from foreigners”.

This negative narrative began to change from the 1990s onwards, as historical circumstances changed. Democratic institutions had been consolidated, EU and EMU (Economic and Monetary Union) membership by then a reality and society was enjoying an unprecedented prosperity. The fall of Soviet communism retroactively disproved the notion of another better model that the country could have followed in the 20th century. At the same time, globalization widened the field of comparison. Previously, Greece was being compared to the most developed countries of in the West; now, the scope of comparison enveloped the entire planet. It was therefore natural to revisit the national narrative under a different perspective, more realistic and ultimately less negative, utilizing the new scientific approaches in history and sociology. We can therefore say with certainty that Greece is not among the “losers” of Modernity. On the contrary, it stayed – with discontinuities and transitions – on the path that brought it, as it wished, closer to the developed and democratic countries; to the “civilized nations” as they were called in the 19th century. It was able to absorb the advances and the great social transformations of Modernity, although it assimilated their easier aspects rather than those that required more complex changes and structures (such as industrialization). In this process, the Greeks themselves bore a great deal of political responsibility for both successes and failures, contrary to the self-victimization stereotype and the myth of the “wronged and dependent nation” that attributed failures to foreigners.

This new national narrative, this new national self-awareness has made great strides in society, but it has faced, and is still facing, two “enemies” from two opposite sides. The first is “banalization” – if I may use this word. By this I refer to some “interpretations” that fall into a historically naive and reassuring description of successes and failures and happy endings as a rule, without searching for their root causes, neither highlighting the dramatic conflicts along the way. The second is the regression to previous patterns of thought. The recent economic crisis brought back outdated schemes, either of the Marxian “Greece is a debt colony” type, or of the elitist “we are an underdeveloped country” type. These perceptions are not about the actual revival of such lines of thought, that are scientifically obsolete, but about the repetition of stereotypes which always outlive scientific theories.

There is a widespread belief in public opinion that the Greek state has always been clientelistic, oversized, inefficient and almost an obstacle to the economic and social development of the country. In your book “Greece: a paradoxically modern country” you propose a different assessment. What is your approach?

I have characterized the State as the “wronged protagonist” of our national development because it has been considered the pre-eminent culprit of the “delayed” modernization in both Marxist and liberal interpretations of the “Greek case”. In public discourse, moreover, the State is identified with Public Administration and its typical problems, while in reality the State is a broader concept and carries out broader functions. I do not deny its negative aspects, but I believe at the same time that it contributed greatly to the modernization of the country. Indeed, it functioned as a conduit for European and international knowledge, expertise, and functions that exceeded the capabilities of society. This is what I mean by the term “paradoxically modern country”. Historically, the driving forces of the country’s modernization were primarily Politics, Geopolitics and modern Institutions. In contrast, capitalism and industry contributed less, as they did not go beyond the micro-scale.

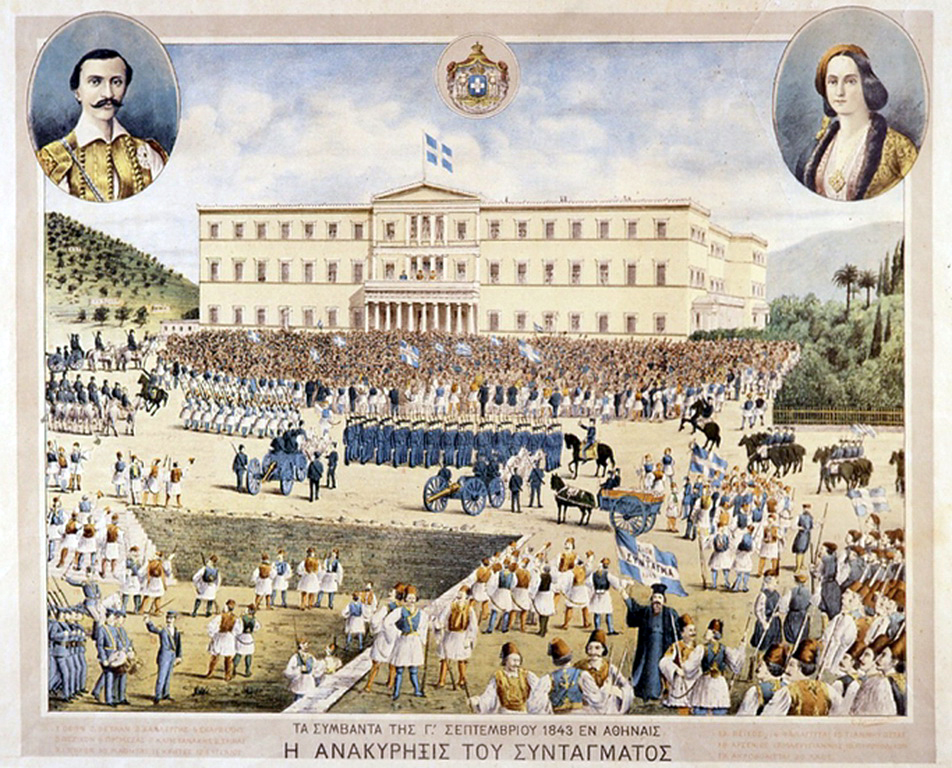

It should be noted that in the long term the Greek State has been parliamentary and democratic. Greece is indeed an interesting case of “early democratization” that has been poorly studied as such in international comparative political sociology. The peculiarity is that the Greek State was created almost from scratch and was almost immediately democratized; we are one of the first countries in Europe to adopt universal male suffrage as early as 1844. Our case was very different to that of the rest of Europe, where long-established aristocratic classes continued to control the state throughout the 19th century, while at the same time the new bourgeois forces that would later dominate the state were beginning to emerge.

This “twin birth” of the Modern Greek State as a democracy had long-lasting consequences. We were used to emphasizing the negative ones: widespread clientelism, the tendency towards political polarization and partisanship, the weight of populism that, as we know, accompanies all modern democracies like a shadow. But equally important were the positive consequences. We established an impressive parliamentary and constitutional tradition. After all, our national political life was not determined by the micro-politics of clientelism, but by the great national goals we set from time to time.

You claim that Greece’s outward orientation played a significant role in determining these goals, correct?

Precisely. These goals always arose from our quest to ‘catch up’ with those ahead – namely, ‘Europe’. In this strategic pursuit (catch up strategy) Greece reaped the benefits of a historical ‘dividend’. Ancient Greece was a focal symbol in the formation process of the modern Europe of nation-states, and conversely, modern Greeks were flattered but at the same time anxious to appear worthy of their “ancestors”. It was a complicated relationship, but, in any case, it helped that the new national consciousness, “Greekness”, was associated right from the beginning with “Europeanness”; it provided a peripheral country like Greece with a strong compass.

How can we join all of the aforesaid together? I have summed up my analysis with the phrase “we are a geopolitical, historical, democratic and small-medium nation”. That is to say, the state and the trans-national relations in our region, the historical dividend and early democratization, all these factors, gave shape and structure to a micro-capitalist society, explaining both its successes and setbacks.

In established interpretive schemes of the “Greek case”, such as those of political dualism and modernization, particular emphasis was placed on the modern / traditional dichotomy. In your book “Greece: a paradoxically modern country”, however, you talk about the ‘modernizing’ functions of tradition. Can you elaborate?

I was not talking about a specifically Greek phenomenon; sociology, history and political economy have dealt with this in many cases. It has been observed in societies going through a transformational phase, that their traditional “communitarian” elements, be it the family or local networks, can serve modernizing goals. To give you two examples: The traditional family can encourage social mobility by investing in the education of its younger members; or, it can ease the social tensions that emerge during the transitional period of moving from the countryside and adapting to life in the city. Also, family and local networks can help entrepreneurship, usually micro-entrepreneurship. All three happened inPost–Civil War Greece.

But at this point I would like to underline an issue that I consider important. Usually, the modern/traditional dichotomy, as presented in analyses based on cultural dualism, calls to mind the East- West dilemma, an ambivalence that traversed the intellectual life of modern Greece. In reality, the “East”, whatever meaning it may have acquired at various times, was never truly an option for Greek society, and even less so for its political leaders. But it was used as a concept that summed up cultural resistances to modernization, or criticisms of modernity. Resistances and criticisms constantly accompanied the emergence of the Modern World everywhere, even in developed societies, and that was not because they were remnants of tradition, but anxieties reproduced concerning the risks of modernity. In this sense, such resistances can serve as a reminder of these dangers.

If the “long” Metapolitefsi began in 1974, with the fall of the dictatorship, and ended in 2008, with the beginning of the financial crisis in Greece, what are the characteristics of the period we are going through now? Can we speak of a dominant political culture like that of the Metapolitefsi period?

Greece suffered in a unique way, and experienced the international financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent Eurozone crisis of 2010 extremely traumatically. It was not a conventional fiscal crisis, nor an ordinary debt crisis. The statist-corporatist development model of the Metapolitefsi essentially collapsed, and along with it, the structure of organized interests that it had produced, as well as the informal intergenerational social contract; incomes fell dramatically and Greece’s place in the EU was at risk. Society was divided, political polarization reached unprecedented -since 1974- levels, and for a period of time the democratic “acquis” of the Metapolitefsi period was called into question. Unlike in other countries that had also signed Memoranda [bailout programs/economic adjustment programmes], the Greek political system did not find a way to reach a general consensus, so that time spent under financial supervision would become shorter and the relevant social costs reduced. Only from 2016 onwards, when all three major political factions had each signed their own memorandum, did political tensions begin to de-escalate.

Since then, some common perceptions have been and are still being formed in society, the most basic of which is the widespread acceptance of Europe and the euro. Essentially, this perception defines the framework for exercising public economic policy for any party that aspires to govern. In a sense, the reaffirmation of the country’s European orientation was the “conclusion” reached by the vast majority of citizens that experienced the crisis. But also in the crises that followed – the corona virus, the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis – broad majorities were formed according to opinion polls as well as observed attitudes. I think that Greek society is more mature, rational and European than we often think, although there is always the risk of derailment.

But can we speak of a “dominant political culture”? I think not – or not yet, for two reasons. First, because the world and international politics are going through a period of great risk and uncertainty. In circumstances of international tensions, Greece usually “imports” these tensions and there is no present or emerging “zeitgeist” that would facilitate convergences at the national level. Second and most important, because the party system and party antagonism that took shape in the aftermath of the 2012 elections has become a self-contained factor of polarization and animosity in our national life. We are, I think, at a strange point: as if society is seeking to tame a fierce and divisive partisan rivalry that has no basis in reality. The issue is that this autonomy of politics is a macro-historical feature of our national evolution; sometimes this worked to our advantage, sometimes to our detriment. Today it works to our detriment by prolonging this divisive atmosphere and civil-war rhetoric.

There is an anxiety about Greece’s place in the world, which seems to have influenced many of the questions asked by Greek social scientists as they try to determine Greece’s position in the context of international hierarchies. What do you think is Greece’s position and prospects in today’s geopolitical environment?

From what we’ve discussed, I believe that the course of this country is characterized by uncertainty, as it is exposed to the sharp turns of History. We experienced this in the recent Eurozone crisis and it would be a good idea to keep it in mind as a lesson. Precisely because Politics, Geopolitics and the quality of Leadership have always played a decisive role in Greek history, we are always exposed to their contingency. We did not have, nor do we have now the safety net of a dynamic economy, for example, to make up for political failures; nor of a public administration that can operate with continuity in periods of political instability or absurdity like those we experienced recently.

In short, Greece is not marching straight towards Progress, nor has it bought a ticket to Hell. But it is going through an era of intense uncertainty, which should serve as a warning, because there are two dangers. The first, again, concerns the international context. We have seen that “Europe” has historically functioned as a factor that bolsters the modernization and extroversion of our country. Today, however, we do not know what weight this Europe will have in the new World that is coming, nor whether the democratic, liberal and progressive values will dominate within it. The second danger concerns the internal situation. Even if Europe finds its way, even if the international framework is balanced, Greece may find itself trapped in the low ranks of the European Union and the global hierarchy. The sources of concern are well known. The productive system remains introverted, lacking in technology, and heavily dependent on private consumption and tourism. Moreover, structural problems are added to all this which can lead to decline. The ecological crisis can take threatening forms in the Mediterranean. The demographic issue will result in an aging society if not addressed in time. Despite successive cuts, the Greek social security system’s long-term viability remains tenuous. I believe that the new national goal for the mid-21st century is to address these risks. We can achieve it, under the condition that we improve our political discourse and party antagonism and upgrade our national reform agenda.

* Interview to: Ioulia Livaditi, Translation: Ioulia Livaditi, Editing: Magda Hatzopoulou

TAGS: METAPOLITEFSI | MODERN GREEK HISTORY