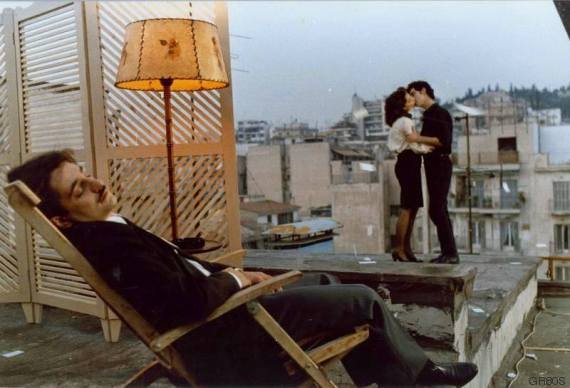

Greece in the Eighties (GR80s) is an impressive exhibition organized by the Municipality of Athens at the Technopolis cultural complex in Athens and at the Onassis Cultural Centre, running from January 25 to March 12. The exhibition introduces visitors to the Greek 80s via four thematic categories -politics, arts, lifestyle and technology- brought to life through documents, objects, audiovisual exhibits and interactive applications spanning 18 pavilions: 1) From “Change” to “Catharsis”, 2) Repression, violence and terrorism, 3) Ideology, 4) Gender, 5) Welfare state, 6) Economy, 7) Housing and public space, 8) Mass culture & consumption, 9) Fashion & Disco Music, 10) Cinema & Audiovisual Culture, 11) Working class culture and demands, 12) Youth cultures, 13) Artistic activity, 14) 80s Library – reading room, 15) Technology, 16) Communication & Mass Media, 17) Auto & Moto culture, and 18) Language: a pervasive presence.

Featuring more than 4,000 exhibits and over 30 events (including art exhibitions, concerts, theatre performances, scientific conferences and educational workshops), the project explores the events that marked a formative decade for the country and largely defined those that followed, taking visitors through a historical, social and cultural review of the politics and way of life; Greece’s glorious victory over favourites Soviet Union in the 1987 FIBA EuroBasket championship, the first Greek private television channel that broadcast in 1989, the huge political rallies in Athens starting with Andreas Papandreou’s famous slogan ‘Allagi’ (change), fashion icon Billy Bo and even a typical 1980s apartment are just some of the cultural and historical milestones revived at the exhibition.

For those born up until the early 1980s there is an emotional attachment to the era, mainly because of the sweeping social and political changes that took place during that period. The 80s represent an idealized era for Greece, characterized by upward social mobility and prosperity; however, for some they also symbolize the beginning of a long process that has lead to the current crisis. Thus, the aim of this event is not to create feelings of nostalgia for the past nor to point the finger at the supposed culprits -rather, it is an effort to record and recreate a complex and multifaceted period of modern history that has left its mark on current generations and may well define future ones.

Apart from the fact that the exhibition is bilingual and thus accessible to foreign visitors, the organizers have placed great emphasis on public participation with a large part of the exhibits (such as photos, clothes, all kinds of souvenirs and memorabilia, toys, pieces of furniture, audiovisual records and much more) coming from volunteers who lent authentic objects of the decade for the show.The chief curators of the exhibition are two academics: Vasilis Vamvakas, assistant professor of Sociology of Communication at the University of Thessaloniki and Panayis Panagiotopoulos, assistant professor Of Sociology at the University of Athens. Panayis Panagiotopoulos and Vassilis Vamvakas had published in 2010 a detailed lexicon entitled “Greece in the 1980s: A Social, Political and Cultural Dictionary” (in Greek, by Epikentro Editions) that plunged us back into the society, politics and culture of the 80s through 264 brief essays and an extensive collection of photos.

Our sister publication, Grèce Hebdo, spoke with professor Panayotopoulos on how Greek society changed in the 80s, the rise of individual along with the persistence of the collective and their paradox cohabitation, the challenges of mass democracy, Greek modernity and why the 80s exert such fascination on us all.

Why use the term “decade” and not, for example, the term “generation” as an element of interpretation?

The term decade is an analytical tool, a way of putting historical time in perspective. A tool that is actually quite new and is not always easy to use. You have the decade of the forties (the WWII), the fifties (reconstruction of the country, etc.) but for example, talking about the 70s or the 60s, we could use concept of the decade only with great caution, because these decades were “cut in half” in Greece. And then there is the decade of the eighties, which is a rather compact period that gives a overall sense of how things were to someone who wants to visit the past in a critical way. Furthermore, it is a period of transformation with characteristics that differ significantly from those of the previous decades. Considering that, and by putting into perspective the trends, for example, in France where the term is used decade as an analytical tool, we decided, together with my colleague Vassilis Vamvakas, to work on the eighties. It is a decade tjat really started with 1981 general elections and the accession of PASOK to power and came crushing down in 1989-1991 with the collapse of the Papandreou system.

Could we talk about a common South-European decade?

I don’t think so, because Italy, for example, has a different trajectory. There is always the possibility of political science comparing Portugal and Spain to Greece, countries that perhaps have more in common with Greece as regards the transition from an authoritarian regime to democracy. But the 80s were a rather interesting and almost singular decade for Greece. It was a decade in which Greece, on one hand, turns inwards (politically and ideologically) and reproduces its own norms and structures. But on the other hand, everyday life, lifestyles and consumerist culture are informed by the global trends of the capitalist and democratic culture that is spreading in the Western world. One can speak of a kind of duality: at the political level, Greece remains stuck in its archaism, while at the level of daily life, lived experience, sexuality, lifestyles, and cultural pluralism, Greece is in line with what is happening in the outside world, in Europe and in the United States.

Could we say the eighties were like a belated May of 1968 for Greece?

I do not think it was a return to the May of ’68, but we can see all the elements of individualization, self-actualization, and promotion of personal well-being that are starting to take hold. At the political level of course, the collective remains very powerful. We are seeing here the formation of a Greek identity with dual dynamics: the same people who are under the grip of the collective, of political affiliation, of clientelism and of statism – they are at the same time functioning as multi-layered beings, hedonists and as recipients of the capitalist, consumerist message of Europe. We find ourselves in a dual structure that will paradoxically work, until the crisis at least. That is, the making of a Greek personality that is dual, the product of a mix between something quite traditional and something ultra-modern.

Compared to what happened in France during the eighties –do you see some common elements?

Yes, there are common elements, such as the development of youth culture, the implementation of social policies and the construction of certain shared understandings about what Europe could be. But there are also major differences: Greek clientelism and statism have no equivalent. And then, French politics are the politics of big country, while Greece is a small country trying to make its way into a first phase of globalization, without really succeeding, in my opinion.

Let’s talk a little about the GR80s exhibition. Who is it addressed to?

This exhibition is addressed to the general public. Its ambition is to break down symbolic barriers and to make the borders of our cultural differences a little more permeable. In recent years very important cultural are events taking place in Athens, but as far as exhibitions, science and the arts are concerned, these events are generally addressed to a limited public, a community of the savvy. Our exhibition is aimed at a wider audience that will be able to reflect on itself through shared experience, the experience of the eighties. In reality, it is addressed to the middle classes in the widest sense: they are a product of the eighties. We are trying to talk to those who have lived in this decade, the people of our generation who are active today, but also to a young audience who hear the echoes of our past through the lives of their parents.

Is it a nostalgic exhibition?

No, it is not. Ultimately, we are trying to use nostalgia as a communication tool, but nothing more. There are of course nostalgic elements like, for example, the reconstruction of an apartment of the eighties built by a team of architects led by Kostas Tsiambaos. The visitor will have the opportunity to enter into a kind of bubble and this could be nostalgic, but at the same time we have the opposite of nostalgia, because this apartment can give a double impression: that of being very close to this era, and at the same time that of being very far away.

What do you hope to inspire to people who visit the exhibition?

We want to inspire a feeling of that despite our antagonisms and our rivalries, we are together. In other words, it is an attempt to bring back to the public sphere the idea of a society in which citizens, despite their cultural, class, political and ideological antagonisms can coexist. I must confess that we would like to present this through a progressive perspective. We also have an ambition of restoring symbolic and cultural value to the middle classes, who for a long time have been left behind by political and social scientists and decried by cultural elites, and of course are now in economic and social danger. So our ambition is to give everyone the opportunity to “relocate” themselves in this historical period, a period not only of antagonisms and confrontations but also of togetherness. In other words, we are trying to go back thirty years in time, so as to make projections into the future.

Can a foreigner visit the exhibition? What do you think she will take away about what is modern Greece?

The exhibition is bilingual. Our hope is that a foreign visitor will see the modernity of contemporary Greece, an aspect that is not obvious, and the creativity of contemporary Greece as well. We hope that she will be able to get a sense of certain parts of the Greek experience that are in opposition to the European experience. For example, the collusion of the Greek state of the Papandreou era with Arab terrorism. I could be of interest to a foreingn visitor to think about how the everyday and the avant-garde adapt to consumerist modernity. To see how Greece enters consumerist culture through music, products, sport or mass culture. Again, we can see the different forms of popular experience -a very interesting pavilion explores how forms of expression of lower classes were different from middle class consumerism.

How did you collect the exhibited objects?

We have worked on several levels: with public or private collections that have loaned us objects, but also, and above all, it was the work with the citizens that has borne fruit: nearly 70% of the pieces that we evaluated and included in our exhibition are objects that until a few weeks ago were locked in closets in various homes. And this is memory work, carried out by the citizens themselves, in collaboration with us. It is memory work on certain objects that were kept and that signify and represent the historical memory of social ascension. That is to say, the people who lend us the objects tell us: “This is something I kept because I could buy it with great difficulty and I was very proud, because it marked my social advancement.”

Tell us a little about social mobility. What do you think were the most striking changes in Greek society during the 1980s?

During this period we observe the phenomenon of mass social upwards mobility, that is to say the formation of a middle class that is increasingly defined in opposition to the working class and that gradually gains access to statist networks. This new class succeeded in organizing a new, modern life, but on a totally rotten economic foundation. This the great contradiction that nobody wants to talk about: how we have a democratic society, centered on the consumerist middle class, without having a competitive economy. This is something that begun in Greece during the 1980s and remains, even today, a subject that is not debated. And we can see that the very rapid and massive social mobility that began in the 1970s and was dramatically accelerated in the 1980s, is a story that in reality poses problems that must be discussed. But on the other hand -and this is a form of justification for the policies of PASOK and Papandreou- we must admit that the working classes of the fifties and sixties were outside consumer society and democratic political life. One can not say that they were totally marginalized, but they were not really integrated into the cultural and consumerist life either. Papandreou understood that this had to change. […]

Did we not see this happen a bit in the sixties in Greece?

During the sixties in Greece one can see a liberation of morals, an ascent of certain concepts, but it all remains very elitist. On the other hand, during the 1980s, the individualistic, hedonistic experience of free time, youth culture, rock culture, sexual liberation, identities, subcultures, and tribalism as well; all this happens on a massive level in Greece.

And was “kitsch” born in the 80s?

Kitsch is something that actually does not exist, it is a concept the dominant classes use to oppose or stigmatize, on the cultural level, the rise of the lower classes. It is a way to show contempt and differentiate ourselves from those that try to take our place, or to “insert themselves in our class”. Kitsch is the the result of a very rapid social rise that hasn´t that the time yet to adjust itself to existing modes of cultural recognition.

The eighties is also the decade of transgression and the cult of anomie…

This is a right-wing criticism, according to which Greek society begins to unravel in the 1980s and this is due to Papandreou’s populism. But this criticism neglects to mention what Greece was like before. Greece had been a clientelist society long before the 80s, but it was a much more inaccessible clientelism. While in the ’80s we have a clientelelism that is totally accessible and uninhibited. I do not agree with that kind of fundamentally negative descriptions of the era, because I think we have to look at the 1980s from the perspective of the defects or the problems of mass democracy. And I do not believe that you can have mass democracy without anomie, without problems, without corruption. There were, of course, catastrophic policies in the 1980s (in education, for example), but I prefer to summarize the era as follows: PASOK gave wrong answers to the right questions. The paradisiacal description of Greece in the sixties and seventies is problematic.

What was the relationship between Athens and the provinces during the 1980s?

It is during the 80’s that those two terms (Athens / provinces) are outlined, put in juxtaposition and problematized. Internal migration is stabilized and ‘eparchia’ is cut off from Athenian life. The 1980s are interesting percicely because the question of the disparity of ways of life begins to be asked. In the 1980s, we cannot really talk about two different worlds between Athens and the rest of the counrty, but there is no common way of life. In short, I believe that in the 1980s, there are still great differences between Athens and ‘eparchia’, but these differences are beginning to be understood as an important issue.

Could we say that this decade exerts a certain fascination on you?

For me, there are of course reasons related to my personal experience but these are are not interesting for an interview. I beleive however that the 80s are fascinating because it is during this period when the social bonds that will build a new society were formed. Modern Greek democratic society is created and organized in the 1980s, not in the 1970s. Furthermore, society changed rapidly during that time: color television, multiple sources of information, many TV channels and newspapers, advertising images, lifestyle etc. An important element to note is that all this constituted a mode of adjustment to the capitalist world that granted a new place to the individual in Greece. This way of empowering the individual goes hand in hand with a still considerable power of the State, the collective and the political. It is a sort of mass individualistic culture, which will paradoxically work for several decades, until today.

* Interviewed by Magdalini Varoucha and Costas Mavroidis, translated to English by Ioulia Livaditi