What do we know about women in Greek Classical Antiquity? Which was their role and the extent of their power, in a traditionally patriarchal society? Does our perception of ancient women do them justice, and which were some examples of women who managed to excel at that time?

Greek News Agenda spoke* with Professor Kostas Vlassopoulos, to try and give answers to some of these questions.

Kostas Vlassopoulos is Professor of Ancient History at the Department of History and Archaeology of the University of Crete and Director of the Department of the Ancient and Byzantine World at the Institute of Mediterranean Studies. He directs a large-scale international research project funded by the European Research Council entitled ‘SLaVEgents: enslaved persons in the making of societies and cultures in Western Eurasia and North Africa, 1000 BCE-300 CE’. She has taught an online course on women in antiquity available on the Mathesis online platform.

The image we have today of the position of women in ancient Greece is that they were completely excluded from public life. Do you think this perception corresponds to reality?

In many ways this is certainly true, but as we shall see, not entirely. First of all, we must start from the obvious, that ancient Greek societies were strongly patriarchal, and there was great inequality between men and women. Women had no right to participate in politics, the courts, or the military in any ancient Greek community. Also, in most cases they were not entitled to carry out legal transactions autonomously, but had to be represented by their male guardian or obtain his consent. Women’s activities in the public sphere were often supervised by the so-called gynaeconomes (women’s supervisors), a kind of morality police. During the Archaic and Classical periods there were no women in public office in their city, with one, but very important exception: the priestesses, who often represented the most important cults of a Greek city. The important role of priestesses suggests that women were not completely excluded from the public sphere: women were citizens of ancient cities, but they only participated in what was considered compatible with the sexist prejudices of the time, primarily participating in religious life.

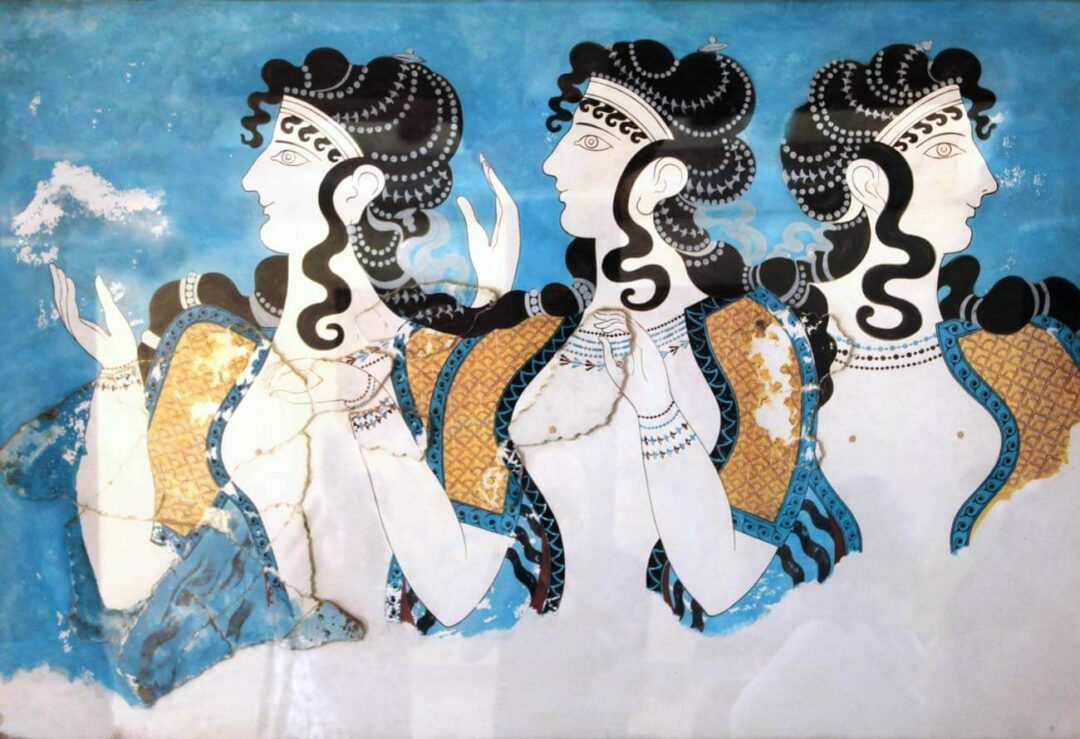

In Minoan culture, women occupied a prominent position and actively participated in all aspects of social life. To what do you attribute this increased presence and what, in your opinion, are the reasons that subsequently led to women having a less important role?

I am not an expert on Minoan culture, so my knowledge of it is limited. In any case, women seem to have had an important role in Minoan public life in terms of rituals, a role similar to that of priestesses in ancient Greece. Although patriarchy was a component of all ancient societies, there were at the same time significant differences from era to era and place to place. Although there is evident inequality between the sexes in Homeric society, we see the poet praising some women for their intellectual abilities, such as Penelope, and other women for their decision-making ability, such as Arete. In the classical era, by contrast, there is a strong sexism towards women. It seems that the development of city states from the archaic period onwards and the institutionalization of the rights of male citizens had a negative impact on the rights and image of women.

Let us come to the position of women in Athens and Sparta in Greek antiquity. What are the main differences between them, what are the reasons behind these differences and what are the opportunities for participation in public life, education and sport?

In both Athens and Sparta most women spent most of their lives in a parallel sphere that included only other women, while men spent most of their time in the male parallel sphere. The two parallel spheres therefore only touched to a limited extent. The more extreme this separation was, the more autonomy women had. In Sparta, where boys left home at an early age and ate as adults in soup kitchens with other men, women had enormous autonomy. At the same time, because of the hereditary system, Spartan women owned a large portion of the land (40% in Aristotle’s time), which gave them great economic and social power. We tend to think of Sparta as a militaristic and male-dominated society: in practice, the exact opposite was often true. When the Spartan kings Agis and Cleomenes tried to radically change the structure of the Spartan city, they knew that they had to convince their mothers and wives to support their measures and mobilize their patronage networks, or else they would fail. And they failed partly because the other Spartans opposed their plans, because they understood that they would lose their wealth and power. Political success in Sparta, then, often came through the support of women. The physical exercise of Spartan women was something that scandalized other Greeks. The dances of young girls at festivals must have been spectacular, while at the same time female homoerotic relations were visible in the public sphere to an extent unthinkable in Athens.

By contrast, in democratic Athens the role and rights of free women were very limited. They could not manage their own property or represent themselves autonomously in the courts, where it was even considered improper to mention the name of a decent woman (they were referred to as mothers, daughters or wives of a man). There was no equivalent in Athens to the women’s sports of Sparta or the girls’ dances at festivals. On the other hand, no Spartan worked for a living, since all the work was done by the helots. Spartan women were therefore by definition members of a wealthy elite. So although the rights of wealthy Athenian women were very limited, the position of poor women in Athens was much better than that of poor women in other Greek cities. Aristotle acknowledged, for example, that the institution of gynaeconomes (women’s supervisors) could not be applied in democracies, because the power of the poor meant that gynaeconomes could not stop women from stepping out of the house to earn a living.

If we were to single out the most famous Greek women we would most likely choose Aspasia, Artemisia and Sappho. In what areas did these women excel and which were, in your opinion, the reasons behind this?

Aspasia was originally from Miletus in Asia Minor and at some point in her life she emigrated to Athens. She became the partner of Pericles, but under the law proposed by Pericles himself, she could not marry him because she was not Athenian, and the child she had with him was illegitimate and he could not become an Athenian citizen. Many sources, both of that time and more recent ones, portray Aspasia as a courtesan and a brothel owner. Given that the basis of these sources is mainly Athenian comedy, we cannot be sure that this was the case, although it is obviously not unlikely. What is striking is that several sources, such as Plato’s Menexenus, describe Aspasia’s impressive intellectual abilities and her conversations with prominent thinkers of the time, which was apparently not common for most decent women of the period.

Artemisia became ruler of Halicarnassus in Asia Minor during the Persian Wars, accompanied Xerxes in his campaign and played an important role on the side of the Persians in the naval battle of Salamis, where she commanded her own trireme. Such a prominent political and military role was unthinkable for women in mainland Greece, but it was relatively common in Asia Minor, where around 400 BC we find Mania in Dardanus commanding an extensive territory and participating in Persian military campaigns. A few decades later, another Artemisia became ruler of Caria with her brother and husband Mausolus, succeeded him after his death, and was essentially responsible for building the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

As for Sappho – the ancient Greeks referred to Homer as “the poet”, and to her as “the poetess”. Sappho was not unique, however, as there were several other women poets with important work, such as Corinna and Nossis. Sappho came from a noble family of Lesbos. Her poems, which have mostly survived in fragmentary form, allow us to study the parallel sphere of women in a truly unique way: the education of young girls, women’s participation in religious life, women’s festivals, the role of women in the social and political conflicts of the time, female homoeroticism. Her poetry is distinguished by her ingenious ability to use established motifs and genres of ancient poetry in an innovative and sensitive way.

Courtesans (hetairai) played a special role in antiquity. What do we know about this category of women?

There is ample lore surrounding courtesans, stemming from the fact that Alexander the Great and his Hellenistic successors had prominent courtesans who acquired great economic and social power. The later sources, which are the most numerous, therefore refer to the courtesans of the Archaic and Classical periods in a rather anachronistic way. The main difference between courtesans and prostitutes was that prostitutes were women who were openly available to everyone in exchange for money, whereas courtesans chose their own partners and made a great effort to disguise the financial aspect of the relationship, giving the client the illusion that it was a real emotional relationship and that they desired them for their characteristics and not for their money. It is often said that the courtesans were educated, but this is very questionable. The main characteristic of the courtesans was that they were trained in the art of seduction, which included good manners, music and dancing. Many courtesans must have been freewomen, but undoubtedly several were slaves. The only woman of the classical period whose biography we can write in sufficient detail was Neaira, who began as a young slave courtesan from Corinth, gained her freedom, and ended up, according to her accusers, illegally impersonating the wife of an Athenian politician. That the woman of the classical era about whom we have the most information is a slave foreign courtesan says a lot about ancient societies, and also about the nature of our sources about women’s lives.

* Interview by Dora Trogadi; translation by Nefeli Mosaidi

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Ancient Athenian & Attic Festivals; Apokries: The Greek Carnival; Carnival Festivities around Greece; Greek and Roman origins of Christmas traditions; Kerameikos, the necropolis of Athens;

TAGS: HISTORY