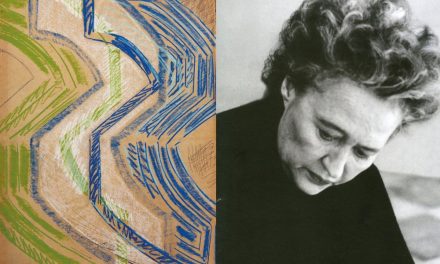

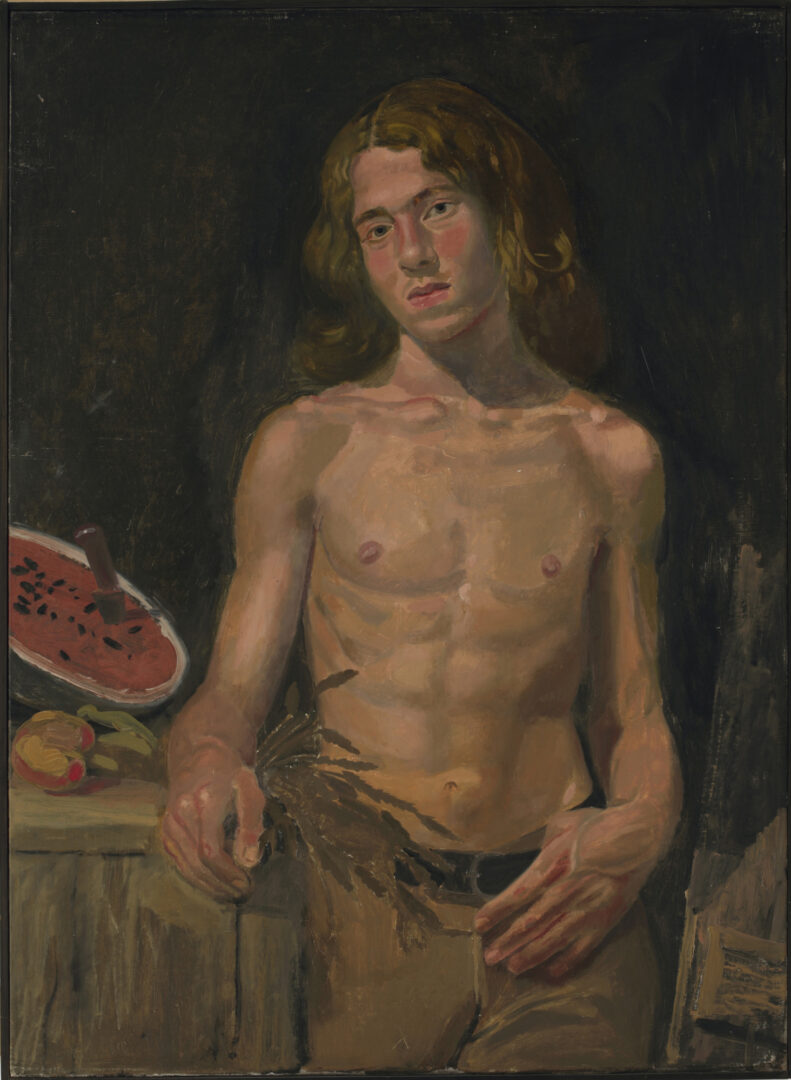

The exhibition I was and I remained a scholar and a student, currently on view at the Yannis Tsarouchis Foundation, provides a wonderful opportunity to pay tribute to Yannis Tsarouchis, one of the most popular and renowned modern Greek painters. Inspired by folk tradition, byzantine art and every day life, he captured the joy of life and established himself as one of the most recognizable and visionary artists. As poet and Nobel Prize laureate Odysseus Elytis once said about Yannis Tsarouchis, highlighting his artistic ingenuity, “A revolutionary can’t be a classic at the same time. But Tsarouchis can”.

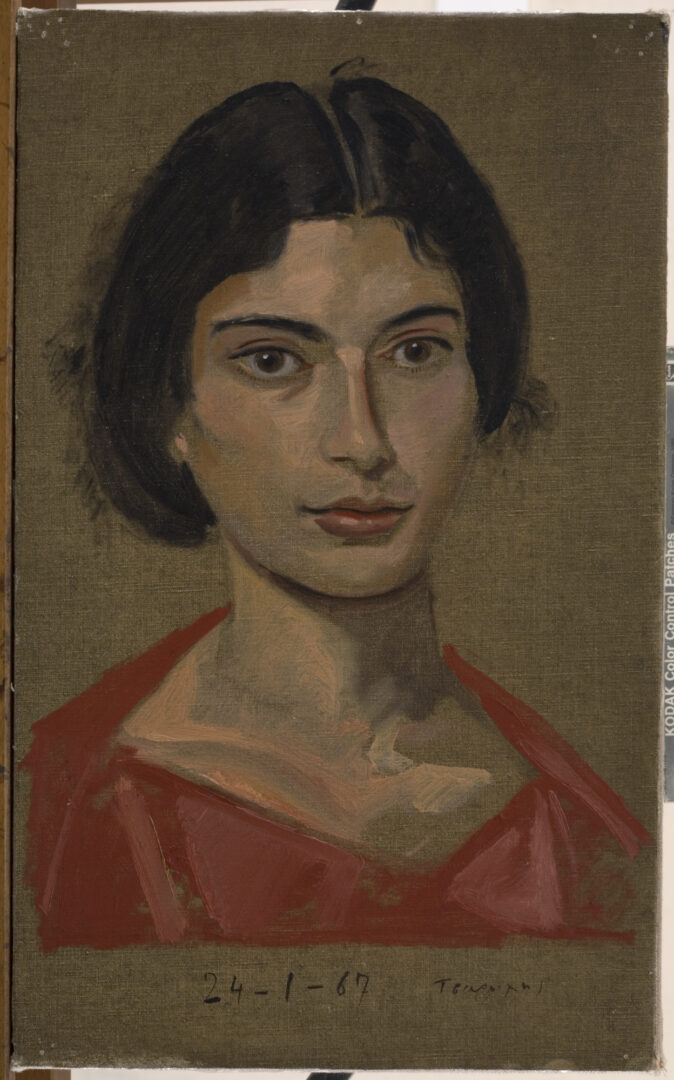

The exhibition, curated by the President of the Foundation, Niki Gripari, is thematically organized covering eight subject areas: Landscapes, Houses, Uniforms and Costumes, Portraits, Religious, Mythological, People with Wings and Still Lives. Viewers can admire artworks painted from life but also imaginary landscapes, mythological and religious paintings, and sets. They are also exposed to his work not only as a painter but also a set and costume designer and director.

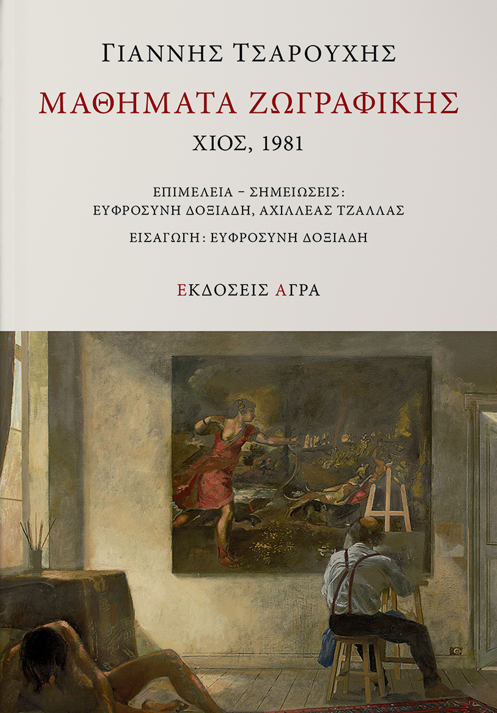

The exhibition coincides with the publication of Mathimata (Lessons), a compilation of lectures Yannis Tsarouchis gave in 1981. This is a remarkable achievement of the Foundation in collaboration with Agra Publications and a precious legacy regarding his perception of art, touching upon a wide range of technical and art history issues.

Ms Niki Gripari, curator of the exhibition and President of the Yiannis Tsarouchis Foundation spoke to Greek News Agenda* about the exhibition and the artist himself.

Which aspects of Yannis Tsarouchis’ personality does the title of the exhibition “I was and I remained a scholar and a student” highlight?

The title of the exhibition was used by Yannis Tsarouchis for the preface of the catalog of his retrospective exhibition in Thessaloniki. He also added “…not always very diligent”.

This is something he had said and written many times. And he meant it. He was close to Fotis Kontoglou as a student and assistant. He learned Byzantine painting by making copies at churches and monasteries he visited and as Kontoglou’s assistant, he worked on the frescoes. Referring to Kontoglou he said “He had made me his true pupil. He instilled in me the best he had: the courage and the love of freedom.”

At the same time, he was a student of Konstantinos Parthenis at the School of Fine Arts. As Tsarouchis pointed out “When Parthenis became a professor at the Polytechnic School, what he taught, was not as original, as many thought. What was very original for Greece was the strictness. Finally! Painting began to be taught in a strict, almost military way” adding that “The respect of talent, how much he relied on talent and how much he sought to find it in his students. That is to say, he asked much more for the expression of talent, rather than being limited to memorizing what he taught. He wanted his students to learn to see and not to imitate.”

Yannis Tsarouchis Foundation

By 1934, he had learned to read Byzantine music and chant. Sotiris Spatharis taught him the technique he used to paint his posters and Eva Palmer Sikelianos taught him to weave.

When he went to Paris for the first time in 1935, to see modern painting, he also went to the theatre and visited the Louvre, where he saw the great painters, such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Courbet. He took pictures of the paintings he saw or imprinted them in his mind. He also listened, observed people, exhibitions, and museums and kept what interested him for his painting.

Until the end of his life, when he was talking about drawings, he would point out what you should pay attention to and he would teach you what he had learned from Parthenis.

Yannis Tsarouchis was a dedicated observer of reality, which is why he painted from life. What were the possibilities offered by this choice?

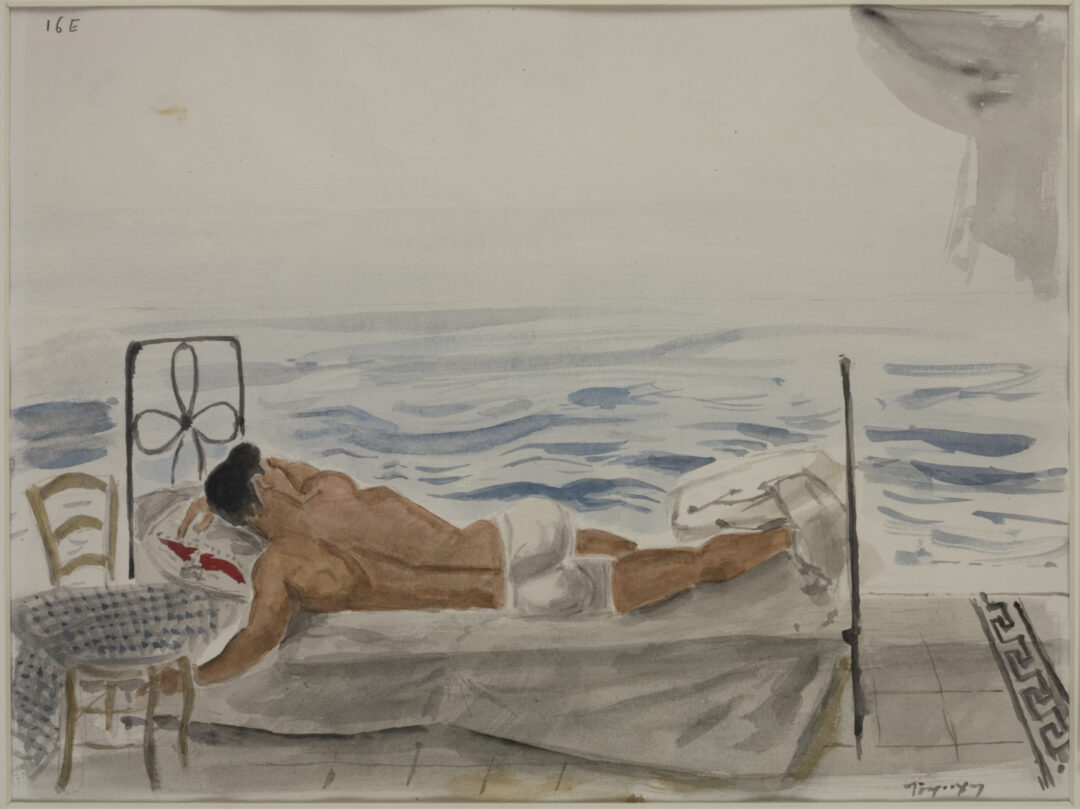

Yannis Tsarouchis was always observing around him, listening to conversations, watching people, studying their movements or what they were wearing. In this way, he was able to convey the liveliness of the coffee shops, landscapes and portraits.

His daily practice of drawing whatever caught his attention made it easy for him to also draw imaginary landscapes, book illustrations, drafts, landscapes, houses, or human figures.

In this respect, he wrote: “Empowered by the study of the natural, I became more aware of the freedoms and abstractions that were essential to the anti-naturalistic realism that interested me.”

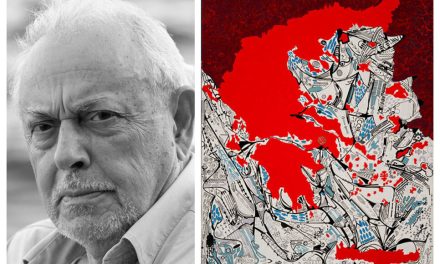

In his works, the timeless unity and the integration of elements from antiquity, folk tradition and Byzantine art are evident. How is this Greekness reflected in his work?

He did not like the term “Greekness”. He wrote: “In 1940, shortly before the Albanian war, I copied the Medusa of the Archaeological Museum, the well-known mosaic of Piraeus, and began two nude studies that were left unfinished due to conscription. The complaints of my few admirers date back to that time….they also began creating systems and theories of Greekness regarding my painting.”

In 1943 he discovered the great painters of the 19th century, the painting of Pompeii, that he visited in 1936 on his return from Paris, and the Greek mosaics: “My desire is to paint like Courbet and Ιngres, but I have neither the courage nor the means. Besides, the era does not allow it. I will later come to accomplish this desire, based on what I have learned from Byzantine Art and Parthenis”, he wrote. I am using his own words. Just by looking at Tsarouchis’ works and drawings, you can see how he is progressing while assimilating all the lessons learned.

One of the aspects highlighted in the exhibition is that of a set designer, director and costume designer. Would you like to say a few words about these aspects of him?

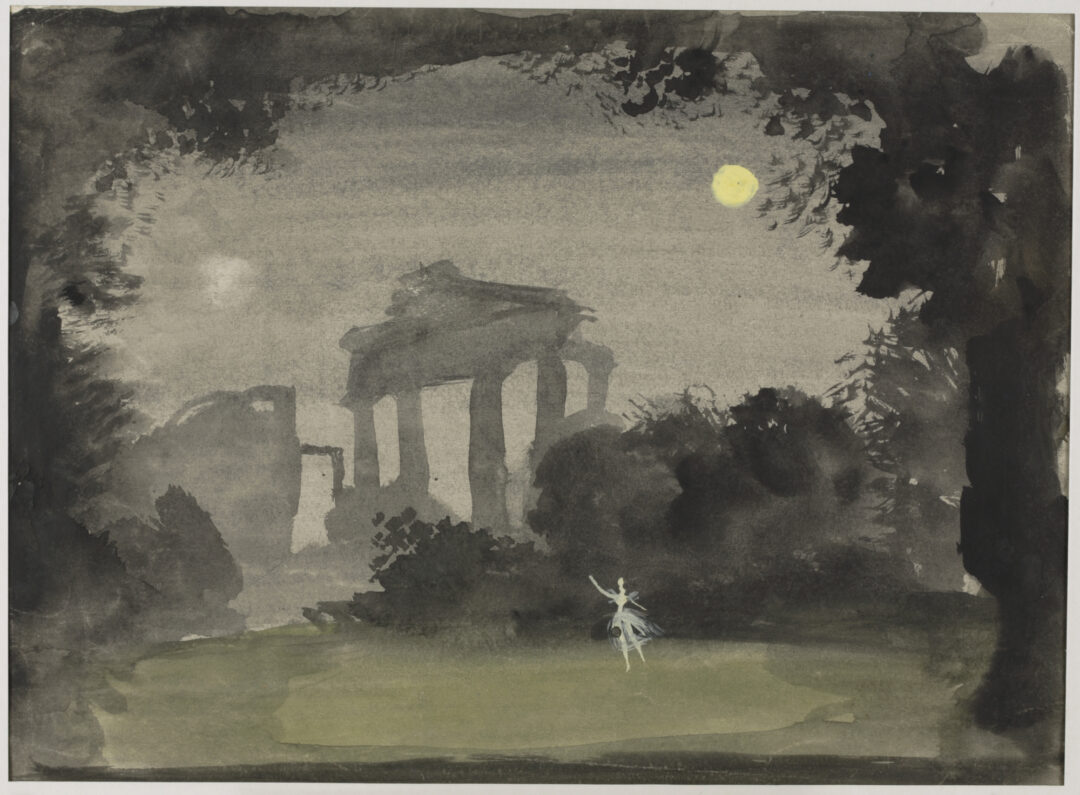

He was involved in the theater from a very young age. His parents would take him with them to the shows they went to and he would usually fall asleep in his mother’s arms. Two performances impressed him very much. Aida at the Kallimarmaro and Xifir Phaler with Panos Aravantinos’ amazing sets and costumes. He liked Aida so much that he gathered the neighborhood kids and his cousins and staged it. He would take his uncle Christos Tsarouchis’ phonograph and play the Aida record. A set showed the moonrise. So he made the moon with paper, tied it to a string, and slowly raised it. He had made a theatre and played tragedies. When his friends grew out of it, he would make his brother watch it so he could have at least one spectator.

When he was 18 he did his first professional job for the National Theater’s theater school. He designed sets and costumes for Princess Malena, commissioned by Fotos Politis. In 1934 he founded the People’s Stage together with Koun and Devaris.

They put on Chortatzis’ Erofili and he made the costumes and sets. He made a living out of theater. He worked with great Greek actors and directors such as Kotopouli, Horn, Andreadis, Paxinou, Minotis, Lambeti, Koun, and Zeffirelli. He did the sets and costumes for Medea with Maria Callas which was performed at the Dallas Civic Opera, at Covent Garden, Epidaurus, and at La Scala in Milan. He also did the sets for Norma, with Maria Callas at Epidaurus.

When he left for Paris, during the dictatorship, he did not work much in theater but painted his ideal performances for tragedies in closed theatres.

In 1977 he performed in his translation, costumes, and lighting of Euripides’ Trojan Women. Soon, he found an open-air parking lot on Kaplanon Street in Athens. He kept the demolished houses as the background, and he dressed the protagonists and the chorus in modern costumes. He presented the army as Greek soldiers, Menelaus as an admiral, and his entourage dressed as Greek sailors. He produced over 160 performances.

What was Yannis Tsarouchis’ relationship with politics and God?

He was not actively involved in politics, but he was very well aware of what was going on. At the beginning of the civil war, the same day I think, he painted the Arrest of the Three Communists. During the civil war, he painted many memorials which highlighted what was happening.

He was painting religious subjects, bringing them into our times. As a young man he had learnt to chant and read Byzantine music, so, whenever he went to church, he wanted to hear it chanted correctly. That’s how he picked the church he would go to.

*Interview by Dora Trogadi (Intro image: Copying Titian, 1971, Oil on canvas, Yannis Tsarouchis Foundation)

Read more: The glory of Greek light through Tsarouchis’ eyes, The home and workshop of Yannis Tsarouchis οpens again, Yannis Tsarouchis: Illustrating an autobiography

TAGS: ARTS