Yiorgis Yerolymbos is a photographer and architect with a Ph.D. from the School of Art and Design of the University of Derby, UK. His photographic work has been published in a number of books on landscape and architectural photography. His work focuses on the interface of nature and culture as it can be exemplified in contemporary topography. He photographs landscapes under transition, places that have sustained changes in the face of modernisation and optimisation of land exploitation.

His research interests include the process of beautification of landscape in contemporary photography, the construction of identity through lived-in space. In 2008, supported by a Fulbright scholarship, he travelled the US by car from East to West and back focusing on the American landscape and how its visitor-user perceives it. He has participated in the Venice Biennale of Architecture twice: in 2012 with large-scale works of the city of Athens and again in 2014, with landscape images of Greece. In 2013 his photographs were included in the main exhibition Everywhere but Now of the 4th Biennale of Thessaloniki, curated by Adelina Von Fürstenberg. Since 2007 and for a decade, he has been the official photographer of the construction of Renzo Piano’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (SNFCC). He recently presented his work in MoMA, New York.

Yiorgis Yerolymbos views the 20th century Greek city as a museum for the next generations and tries to give to the world his whole self while photographing. He spoke with Greek News Agenda* about his work on the construction of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, architectural photography, photography in Greece, Athens’ image and the Greek urban landscape:

You were asked to capture the work at and the construction of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center? How would you describe this experience?

It was an incredible experience and granted me the best decade of my life. I enjoyed it enormously, and had fun while working. I had the opportunity to meet thousands of people and make friends for life. On its heyday, we had more than 5.500 people in the construction site of all nationalities and backgrounds, people from India and Pakistan, from Germany, Italy, Albania and Poland; I worked with every single one of them, and consider myself very fortunate to have done so, I was somehow a privileged spectator of a closed environment which was not accessible to the general audience due to safety reasons. As you can understand, a construction site is always secured; one cannot enter without clearance, and has to wear a helmet, a jacket or special shoes in order not to step on something. It is a protected environment and I was privileged to be one of the very few witnesses of its day-by-day changes. They were so fast to take place, ephemeral in a way that they could not be found the very next day. The photographs taken are the only proof that they ever existed.

What does a building like the SNFCC add to the image of Athens?

I would say the world for a number of reasons, but most importantly, I think that Renzo Piano’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center adds a modern contemporary building to this city that already had enough ancient ones to demonstrate.

In Athens, as one easily imagines, there is no lack of ancient locations and sights to visit. What was missing was a building of contemporary architecture of the highest level, a signature building if you like. And, before the Niarchos Centre, we could only find that in power buildings of restricted access. For example, the Ethinki Bank’s Mario Botta building in Kotzia Square or Walter Gropius’ the American Embassy. So, I would consider the Niarchos Centre as the first signature building by a star architect that belongs to everybody and it is there for everybody. I think this is quite significant at this time and age.

What led you into photography? When did you realize that this is what you want to do with your life?

I was trained both as an architect and a photographer. I chose to become a photographer for two main reasons. First, being that with photography you to get to visit other people’ s worlds, which helps one enormously to broaden ones horizons. You find yourself in a environment of constant learning. For example, you get to an oil refinery to take photos, you meet the people there, you understand the process and you spend time with them, and this is a rare opportunity that very few people have. Again, you have a privileged point of view. Whatever subject matter you approach, you find yourself in multiple worlds so to speak, thus enriching your experience. Secondly and most importantly, I wanted to have a chance to see the world. It may be incredible, but the quality of world-seeing that photography provides is unparallel to any other profession, one could argue, and I think I am intitled to say so as photography has taken me everywhere in Greece, although I am pretty sure I have missed some parts (Amorgos comes to mind…). I have seen my fair share of the world precisely because I had to photograph it.

What is photography for you? What do you express through architectural photography?

Somebody far more intelligent and far more eloquent than myself gave the very definition of what photography is. It was the great Robert Adams, one of the photographers from the New Topographics movement in the 1970s, who said “what photography traditionally tries to do is to show what is past, present and future in one shot”. For a photograph to work you need ghosts of the past, the daily news and prophecy. So I think this is what makes a photograph interesting. In a successful photograph, you recognise the updated information of the current world, and at the same time you trace the past and from a proposal for the future. It goes deeper than the visual surface and that is, to my mind at least, what makes photography interesting.

As far as architectural photography is concerned, architectural photography is exactly what the title describes. It is photography of architecture and at the same time the architecture of photography itself, a structured photograph if you like and it is precisely this that takes a lot of time to reach. You need follow a very slow and careful process, you work with a tripod, you need to have a big view camera, and take your time; and through this process you methodically compose your photography. You look at the world in a completely different pace and you give it your whole self. And this puts you, at the end of the day, in an extraordinary position to appreciate the world far more than the average person who shoots thousands of photos a day and then moves on to the next point of interest.

If I have to photograph a monument, it will take me hours and hours to set everything, to look at it, to take my time and as a result I start to experience it differently. That is what architectural photography offers, in my view.

What are your thoughts regarding photography in Greece?

We really have photography of the highest level in Greece and there are fellow photographers whom I highly appreciate. If one would like to point out a problem is that photographers they will go as far as their own strength and means go, there is no institution to support or back them up. Artists of the medium will have to do everything by themselves and unfortunately the same applies to all kind of art in our country.

And this is not the case abroad, for example, all the established photographers that we know from the US or Germany enjoy the support of a number of institutions that help an artist to advance his or her work beyond his or her own reach; museums, galleries, collections that support the work and help an artist to get to the next level.

We, also, experience the same problem in education. The education system in photography, for example, is a very poor one and therefore only you have to be really exceptional to survive once you left school. Unfortunately, most of the people in photography once they earn a degree, they find themselves in a position were they have to make a living by doing something else, and practice photography as a hobby instead of a full time profession. I am afraid that the same applies in the overwhelming majority of the creative, so to speak, professions. We are alone. So if somebody has the determination and the strength to go down a lonely path, fine, we hear from him. If not, that is pretty much it.

What does the Greek city mean to you? How would you describe it?

Well, it depends really. I recently had the opportunity to describe Athens as a frozen wave, seen from a distance. If you go up the hill on Ymittos or Lykavitos, the city resembles like a huge wave of cement frozen in its current form. The city has sped basically towards all directions: it knows no barriers, no limits; and you can literally see it everywhere. It expands. There is no planning or anything of the sort. To be frank, the city is as important to me as it is to most fellow Greeks, it is our chosen habitat. The majority of us, we are people of the cities; half of the country’ s population lives in Athens, one million lives in Thessaloniki and most others live in the major cities around the country. And although we do not value Greek cities, it would be fair to admit that it is just the outcome of our own actions. We the people are responsible for the way Greek cities look like. It is our doing, our making, like looking into a mirror: it is us, whether we like what we see or not.

In the Greek urban landscape there are elements that characterize it and attribute to the Greek particularity and make it special. What is Greek particularity for you and where do you find it?

I have been a landscape photographer for the last 22-23 years and I had the opportunity to visit every single part of this country, so I would say an extraordinary diversity found within short distances. Our planet is beautiful everywhere, but the one thing I believe can be particularly distinct in our country is the variety of our landscape in such a small part of the world. For example, if one drives from Athens to Thessaloniki, one will experience mountains, lakes, and seascapes every 50 kilometres, to experience the same in France one would have to drive for a day and a half to see the scenery change. The same applies in the US, in Kansas, for example, I drove for 3 days through cornfields, 3 days of driving in flat. From the valley of Thessaloniki where everything is also flat to mountain Olympus which can be found only 30 minutes down the road, to Iliki Lake and to the Pindos mountain range, this diversity in such sort distance is literally amazing. It’ s an exceptional characteristic that inspires travelling and makes this country an attractive destination to visit again and again.

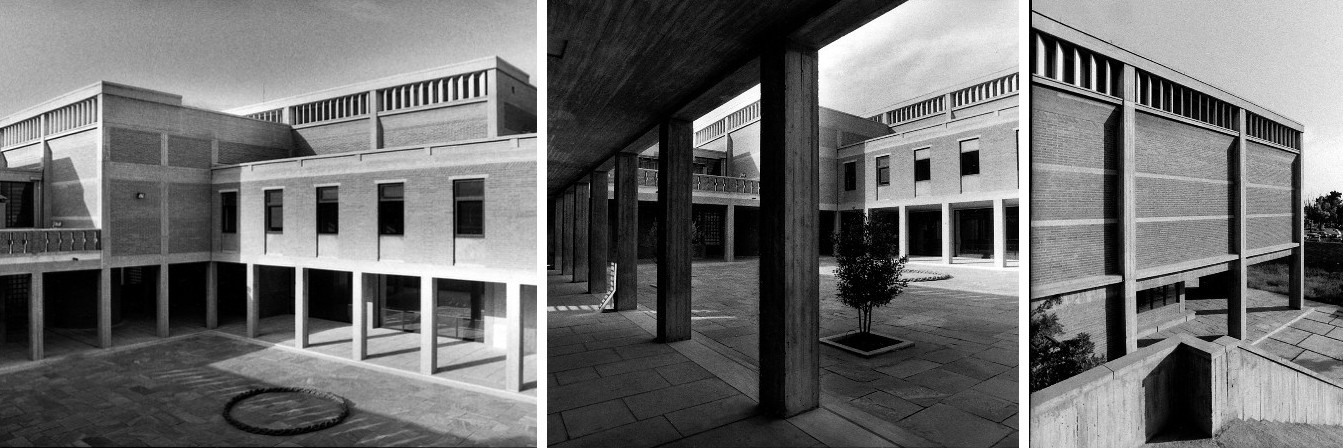

Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki (architect: Kyriakos Krokos, photographed by Yiorgis Yerolymbos)

The tension between Greekness and modernity is an important aspect of the Greek urban landscape. Typical examples are architects Dimitris Pikionis and Kyriakos Krokos, whose work has references to the Greek architectural tradition that tries to emerge through the modern waves. How do you feel about the contemporary discourse between Greekness and modernity? How does Greek modernity exist in the urban landscape and where can it be found?

In many people’s view, there is no clash between modernity and locality; Greekness is the subject in hand. It was actually one of the founders of the international style, the modern movement, and Bauhaus’ director Walter Gropius, who argued that the modern movement in architecture celebrates locality. The more successful a modern style is, the more it transcends, celebrates the local elements and features.

Now, where can Greek modernity be found in the urban landscape? Should we refer to the very successful example of Thessaloniki’s new sea front? We should be reminded that there was a huge battle at the time when plans for the new sea front were unveiled, and most of the people initially thought of it as too western, too modern, by arguing that the Byzantine past of the city has not been celebrated. Both the architects and the architectural community responded by saying that Thessaloniki had already enough of beautiful Byzantine architecture and is, certainly, in no need to add more. What it lacked, on the other hand, was a contemporary public space.

In short, we don’ t need to create everything in the form of the Cycladic house. We can experiment with new styles and ideas and, having said that, it was Le Corbusier who was gravely impressed by Cycladic architecture and used it to create the international style. So, I would go back to my point that modernity and locality, when applied successfully, intertwine. They become one interesting new form that pushes the envelope forward. Otherwise we go round the same thing again and again without really going anywhere.

What does the human-altered landscape mean for Greek Modernity? What in particular characterizes this man altered Greek landscape?

The human-altered Greek landscape is a landscape in an interim phase. It is stuck in the middle. It’ s not a pure landscape, pristine and beautiful, and it’ s not an urban environment either. For every single illicit cement structure to house a rent-a-bike or rooms to let facility our institutions were unable to stop it on time, or fix it afterwards. It seems we are bound for ever to live in an environment cement “skeletons” will be a permanent part of our landscape. This can, also, be found in our cities, everywhere around the country you can see these leftovers marring the landscape. I would say that the foremost characteristic of the human altered landscape in Greece is precisely this – stuck in the middle, in an interim phase, it doesn’ t go back and doesn’ t go forward. It is there, in many respects and works as a metaphor for what we experience right now in every single aspect of our lives.

The urban landscape has changed. In the 70’s we already had a plethora of apartment buildings emerging. The apartment buildings are a distinctive feature of Athens. How do such buildings shape the image of the city?

They do so and, possibly, in a very constructive way, as far as I am concerned. What do I mean by this? It has been argued by a number of architects and historians among whom, Jean Sauvaget and Aldo Rossi that has said that architecture represents the petrification of a society. In a few words, architecture freezes time and what can one discover of the construction of that era is the circumstances and values of that era. For example, Paris is the petrification of the 19th century and the same can be argued about London for example and the Victorian period. Equally, Athens will be the petrification of 20th century.

How did these buildings come about? Constructors approached small homeowners and offered 2 or 3 apartments for their land, on which they would built apartment buildings making a profit from the sale of the rest of the apartments. In the course of time this period ended and now, Athens and every single Greek city have frozen in a time period that reminds us of the 60’s, the 70’s and the 80’s, working, so to speak, as a living museum of that particular time frame. People will be visiting Athens in 200 years time to see how people lived in the 20th century, in the same way that we visit a medieval city in Italy.

We are used to seeing Greece projected abroad through photography in a romantic way. In your work, it’s a different case. You show that great projects exist but also continue being built. We see imposing buildings, great architectural buildings that stand out. How does all this happen? What makes you project Greece that way?

Frank Gohlke famously said that “where we live is far more important than where we visit”. You go to a mountain, you take a shot of a beautiful landscape and then you go back to a small alley in Pagkrati or Kypseli or anywhere in the suburbs and you don’ t appreciate that as a landscape. You look at a mountain or cove and that is the only landscape you acknowledge as important, your everyday surrounding are pale in comparison, or so you think.

Truth is that landscape is where we live, not where we visit, and it is the most important landscape of all exactly because we are shaped in it. So, if it looks like a environment consisting of cement buildings in an alley with a few or no trees at all, then this is the defining landscape for us You don’ t have to disregard it or throw it away. And that, I think, explains to a large extent why I photograph Greece in a way different to romantic portrayals: because I don’ t visit it, I live it, it is mine as I am hers, I am not a visitor or a tourist, it is my home.

We have reached a point in our recent history where we constantly complain about literally everything: we think ourselves as the best, we blame others for our shortcomings and I honestly think I had enough of this attitude. Considering myself a person with love of country – defining such a person as somebody who wants his country to be better, not necessary recognizing it as such- I would like to see it to a cleaner, more structured and lawful, a better place for everybody to come and visit time and time again.

And in that respect, I point my camera towards our county’s best parts. I want to show it as the dynamic, interesting and diverse country that I hope it is, that I wish it to be. I photograph multiple aspects and visit many of its parts, even the now so interesting ones, which can disappoint at times, but insist that if we look at it in a more constructive way, we will appreciate it more and eventually take good care of it. That is why I photograph what I consider interesting architecture from exciting young Greek architects that I consider worth promoting: as many of my photographs are published in international magazines, I would love to do my part for the world to see that this country produces interesting architecture and art of the highest quality.

*Interview by Veroi Katsarou

More Yiorgis Yerolymbos Interviews: Uncube; arcspace.com; lovegreece.com; Bookshelf: Orthographs – The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center

N.N.