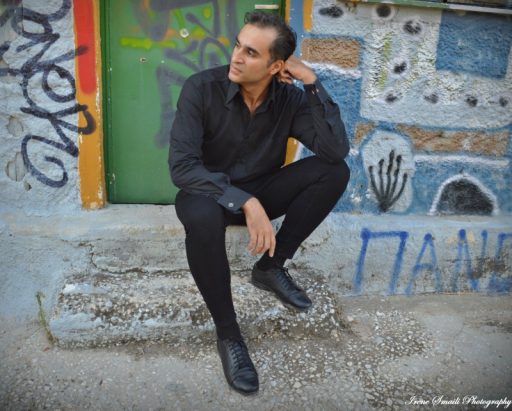

Nikolas Karagiaouris is a baritone with a rich repertoire and multiple collaborations with some of Greece’s most important artists and institutions, such as the Greek National Opera. Born in Patras, he studied violin and piano at the Municipal Conservatory of Patras, and completed his Vocal Music and Drama studies at the Athens Conservatory.

Karagiaouris has won prizes in opera competitions in Athens and Thessaloniki, and earned a scholarship from the Greek Wagner Association to participate in the Bayreuth fellowship programme (2012). His repertoire includes major roles in operas such as The Magic Flute, Carmen, The Elixir of Love, La Bohème, etc., as well as in religious music works by Handel, Rossini, Bach and Fore, while he has also appeared in roles in Greek operettas and contemporary Greek operas.

Greek News Agenda spoke* to Nikolas Karagiaouris on the history of Greek opera, as well as his thoughts on the genre’s future.

You have starred (in 2014 and again in 2016) in The Murderess, an important contemporary Greek opera, by composer Giorgos Koumendakis, who has also been the artistic director of the Greek National Opera (GNO) since 2016. What were the particularities of such a performance, taking into consideration the unique character of an opera with a Greek libretto and musical influences from Greek folk tradition?

The Murderess has been one of my happiest experiences on stage. Contemporary Greek opera is a rare and precious thing that has been thankfully met with well-deserved enthusiasm in recent years.

When a classical singer performs in his native language, he inevitably brings with him the resonance, the lived experience and emotions of an entire musical tradition, which is, in my opinion, what has set Greek opera apart for the last 150 years and made it so charged. Let’s not forget that the first Greek opera was The Parliamentary Candidate by Spyridon Xyndas from Corfu, in 1867. Other composers followed later, mainly of the Ionian School.

The GNO has since commissioned and staged more Greek language productions, often of an equally experimental character, with remarkable success. Do you think that Greek opera has a big future ahead of it?

Greek opera may not draw on a long tradition compared to French, Italian or German works, yet it has given us true gems. Our country is full of extremely talented composers who have freed themselves from pointless comparison and have found a voice of their own, drawing inspiration from the richness of Greek history, including Modern Greek history, as is the case of Pavlos Carrer with his works Marco Bozzari, Despo, Frosini etc. I am very optimistic about the future of Greek opera.

Long before the current momentum enjoyed by Greek opera, Greek musical theatre was associated with operetta, an extremely popular genre at the beginning of the 20th century that had gradually lost its appeal in the age of television. Lately however it appears to be making a comeback – a recent example being the production The princess of Sazan (1915) by Spyridon-Filiskos Samaras, in which you also starred, last June. Do you think there is really a re-appreciation of this genre? Has the audience’s interest in such works revived?

Long before the current momentum enjoyed by Greek opera, Greek musical theatre was associated with operetta, an extremely popular genre at the beginning of the 20th century that had gradually lost its appeal in the age of television. Lately however it appears to be making a comeback – a recent example being the production The princess of Sazan (1915) by Spyridon-Filiskos Samaras, in which you also starred, last June. Do you think there is really a re-appreciation of this genre? Has the audience’s interest in such works revived?

In its heyday, the Greek operetta was the most popular type of music. It’s no coincidence that it stood the test of time, as many tunes coming from there have been embedded in our collective memory and are still hummed by younger generations today. It deals with familiar themes and emotions, so for me its revival was just a matter of time.

Do younger viewers show interest in such works? Having significant experience with Greek operettas, what would you say are their defining features?

As spectators, when we listen to musical themes that we can memorise, and when these conform to the vocal standards of the opera, we are usually impressed and flattered. This combination is in my opinion the catalyst that gives operettas their unique character and makes them so popular.

Do modern productions usually try to remain faithful to the spirit of the epoch, or do they introduce innovative elements?

I feel that the only loyalty owed by any creator is to the lyrics and music; in short, to the composition, the music notation. I believe it’s almost impossible to remain faithful to the spirit of a bygone time alone. Each staging becomes interesting when it is imbued with the particular perception, spirit, aesthetics and philosophy of its contributors.

You have also starred in more popular productions, from children’s operas to musicals by N. Karvelas, next to Anna Vissi, as well as a TV show. Do you believe that a wide range in repertoire is an added quality as opposed to the strict observance of what is often associated with the practice of high art, which perhaps leads to elitism?

I have the utmost admiration for my colleagues who remain committed exclusively to the opera. They are an inspiration to me and I consider them blessed. But for me personally, what weighs more is the notion of change and adventure.

In every music genre I was lucky to have worked with people who love and honour their art. In this light, I am proud of all my collaborations so far; I have learnt a lot from them, forged my technique and expanded my range of experience.

After all, talking about quality and commercialism, lowbrow and highbrow can lead to an endless and, in my opinion, pointless discussion. What counts for me is doing one’s work with passion and devotion.

I suspect that the reason I have difficulty answering this question and picking out one part is perhaps this: in my consciousness and memory, it’s not so much the part itself that I keep, but rather the music, the essence of my collaborations and the extent of my transformation.

*Interview by Nefeli Mosaidi (All photos ©Irene Smaili Photography)

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Vassilis Karamitsanis “The Greek National Opera has decisively entered a digital path”; Composer Minas Borboudakis on his work in 21st-century classical music; Vangelis Hatziyannidis: “Writing for an opera was like a puzzle I really enjoyed”