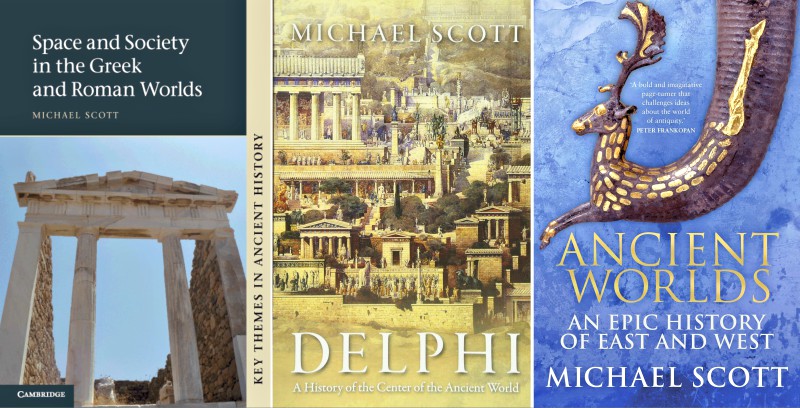

Professor Michael Scott is one of the most prominent and passionate classicists in Britain, also well known for his public engagement and outreach work as a speaker and broadcaster. His research and teaching focuses on aspects of ancient Greek and Roman society, as well as ancient Global History, while he has written several books on the ancient Mediterranean world as well as ancient Global History. In 2015, Scott was declared an honorary Citizen of Delphi in recognition of his work related to the sanctuary of Delphi.

Michael Scott is a Professor in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick and member of Warwick’s Global History and Culture Centre. He is a National Teaching Fellow and Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, President of the Lytham Snt Annes Classical Association and in 2019 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. He has written and presented a range of TV and Radio programmes for National Geographic, History Channel, Nova, BBC & ITV, including Delphi: bellybutton of the ancient world (BBC4), Who were the Greeks? (BBC2) and Ancient Invisible Cities (BBC2).

On 12 February Professor Scott gave an illustrated talk to the Anglo-Hellenic League and the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies about the making of his latest BBC2 TV series, Ancient Invisible Cities, which combines real-life exploration of hard-to-reach ancient locations with high resolution laser-scanning and virtual reality to open up spaces and landscapes never before seen on TV.

On this occasion, Professor Scott was interviewed by the Press & Communications Office at the Embassy of Greece in London, and spoke about the portrayal of ancient Greece throughout the centuries and the contribution of ancient Greek studies to self-knowledge. Studying the ancient Greek and Roman world is crucial to a good education, he notes, while highlighting the possibilities of pedagogical and technological innovation in the field of classics, as well as the importance of engaging with the wider public in discussions about the ancient world.

How did you decide to study classics?

How did you decide to study classics?

I was 17 and spent my 17th birthday in the ancient sanctuary of Olympia, on a school trip to Greece. Up to that point I had not intended to study Classics. But spending that day in such a wonderful ancient site completely changed my mind. I have never looked back since.

How have portrayals of ancient Greece changed over the centuries?

Dramatically! The ancient Romans did a good job of portraying ancient Athenian democracy for example as little more than ‘mob rule’ – an impression whose legacy can still be seen in the debates about the American Constitution by the US Founding Fathers. The 19th century however saw a crucial change in attitudes towards Athenian democracy and to ancient Greece more generally, as many European nations in particular began to express a direct link to the political, philosophical and cultural achievements of the ancient Greeks. It was at this time also that the archaeological investigation of ancient Greece began in earnest, with the Acropolis declared the first archaeological site, changing our understanding of the physical world of the ancient Greeks. But even today, the best known aspects of ancient Greece remain its philosophical debates, the democracy of Athens, and its military activities, particularly in the struggle against the Persians in the 5th century BC and in the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC.

In one of your lectures you argued that “studying the ancient Greeks actually offers us a mirror with which to study ourselves.” How relevant is ancient Greece in today’s world? What can we learn from the ancients about ourselves?

It is because we, as modern nations, have, particularly in the last two centuries, claimed such a strong link to the political, cultural and philosophical achievements of the ancient Greeks, that as a result studying the ancient Greeks tells us about ourselves. By studying them, we not only learn more about their achievements, but also more about ourselves as we continually reflect on the similarities and differences between us and them.

Classics used to be an integral part of a good education. To what extent do you feel that this still applies today?

Those who study the ancient Greek and Roman worlds today have worked very hard to ensure that the study of these incredible ancient societies is NOT only the privilege of those who go to expensive private schools. We fundamentally believe that studying the ancient Greek and Roman worlds is of importance and use to every child in every school – and thus that it should be an integral part of every education – that indeed it is crucial to a good education. We in universities work closely with teachers in schools across the country, as well as with organisations like Classics for All to ensure everyone has a chance to study this incredible moment in our bigger human story.

From the making of Ancient Invisible Cities

From the making of Ancient Invisible Cities

You have been awarded the National Teaching Fellowship for your contribution to teaching in higher education. What are the possibilities of pedagogical innovation in the field of classics?

Endless. It is often remarked at my university – the University of Warwick – that despite the fact that the Classics department teaches about some of the oldest material anywhere in the university, it is often doing so using the most advanced and new technological equipment or using the latest pedagogical techniques and ideas. Studying Classics is the study of what makes two ancient cultures tick – and there is a vast array of fun, innovative and exciting ways to do that. It is what makes my job the most fun – having the chance to constantly innovate in the ways I teach the ancient world.

You recently wrote a book on ancient Greece for 8-year-old children. How can life in ancient Greece capture the imagination of young children?

I think young children are always fascinated by ancient cultures that can be so different from our own. In the UK, all children aged 7-9 learn about the ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians as part of the national curriculum. But we currently don’t then continue that learning as a core part of the curriculum into later years – when we should!

You have written and presented some of the most fascinating documentaries on ancient Greece. What are the challenges in visualising ancient Greece on TV?

Ancient Greece has a unique problem not shared by its cousin Ancient Rome. Ancient Greece was never one place – it was a patchwork of other 1000 poleis, all quite different from one another. You cannot thus look at Athens and see Greece in the way that you can look at the city of Rome and see the Roman Empire. As such, the public I think simply does not have in their heads such a clear picture of ancient Greece as ancient Rome and this has all sorts of implications for how successfully any documentary, drama or film can represent the ancient Greek world (when no one is in agreement about how it looked or felt). Again the comparison here is with ancient Rome – where the public I think can more easily visualise what ancient Rome look and felt like – and such can buy into films set in these landscapes (think of the success of Gladiator for example).

From the making of Ancient Invisible Cities

From the making of Ancient Invisible Cities

How can the use of digital technology make the ancient world more accessible to the wider public, and especially to younger generations?

I have been lucky enough to be involved in a BBC documentary series Ancient Invisible Cities, which uses laser scanning to create 3D scans and VR worlds of ancient sites. I think these techniques have huge potential to help make the ancient Greek world more accessible to the wider public, because they offer a middle way between just looking at ruins and fully re-creating an ancient landscape which no one can agree on. I think the technology also allows us to think about how the ancient Greeks constructed their buildings, and thus puts the emphasis on the incredible craftsmanship of its artisans and architects, as well as the skill of the workmen actually building these structures, allowing us to access a different level of ancient Greek society from those normally most visible in the ancient texts (politicians, military generals, dramatists or philosophers)

You regularly take part in live online Q&As, answering questions and sharing the latest news and events on classics. How important is engagement with the wider public in debate and discussion about the ancient world?

I see it as fundamentally part of the job of being an academic to engage with as wide an audience as possible over why I think this topic is worth studying. I also see huge benefit in the two-way dialogue between my research, my teaching and my engagement with different audiences, with each of those strands of my work benefitting from being in contact with the others. I think also right now, especially as the ancient world is being employed as justification for a myriad of ideas and values in our modern society, some of which are absolutely the antithesis of the reality of the ancient Greek world, that we engaged actively in that debate over what the ancient world can and should be taken to mean, support, and justify.

In a recent article in the Guardian, you wrote that modern Athens is a “battleground of an ancient versus a modern world”. In your documentary Ancient Invisible Cities: Athens some of the most hidden aspects of ancient Athens are revealed. Which of these aspects do you find most fascinating?

Any city with an important ancient past finds itself something of a battleground: constantly having to weigh up the destruction of modern buildings to uncover ancient ones, or leaving ancient wonders covered over in order to prioritise modern structures. What we tried to do in Ancient Invisible Cities was to explore some of the ancient spaces that have ended up out of sight and reach of the ordinary visitor and use the laser scanning technology to make them visitable for everyone via laser scans and Virtual Reality.

Michael Scott in Delphi

Michael Scott in Delphi

In 2015, you were made an honorary Citizenship of Delphi, in recognition of your work related to the sanctuary of Delphi. What is unique about Delphi? In what ways did Delphi shape the ancient world?

It was a huge honour for me to be made an Honorary Citizen of Delphi. Delphi is like no other place on earth – an incredibly important ancient site in a beautiful and wonderous location, which has a magical power to it felt by I think everyone who visits. In the ancient word, Delphi was one of the most important locations across the Mediterranean and beyond: we even find sayings from the oracle of Delphi inscribed on a monument at the ancient site of Ai Khanoum in modern-day Afghanistan!

On 20 February 2019 you delivered your professorial inaugural lecture at the University of Warwick. What are your plans for the future?

My research interests at the moment are focused on the ways in which different ancient cultures interacted with one another both inside and outside the Mediterranean, across the ancient Silk Roads, all the way to China. At the same time, I am also interested in bringing modern understandings of cognitive behaviour and psychology to the study of the ancient Greek world, particularly the study of ancient Greek religious ritual. You can watch my inaugural lecture here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pa7aZHeuKSg

Read more via Greek News Agenda: Dr Stephen Miller on uncovering the Sanctuary of Zeus and the revival of the Nemean Games; Sharon Gerstel: “Byzantine History opened my eyes to a culture that has long been marginalized in our studies”; Reading Greece | Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek; Study Archaeology in Greece: English-taught Undergraduate and Postgraduate Courses

TAGS: ARCHEOLOGY | HERITAGE | HISTORY | MODERN GREEK STUDIES