Alexis Panselinos (born 1943 in Athens, Greece) is an award-winning Greek novelist and translator. He is the son of the poet and author Assimakis Panselinos (1903-1984) and Ephie Pliatsika-Panselinos (1907-1997), also a poet and novelist. He studied Law at the University of Athens. He is a resident of Athens, married to the novelist Lucy Dervis.

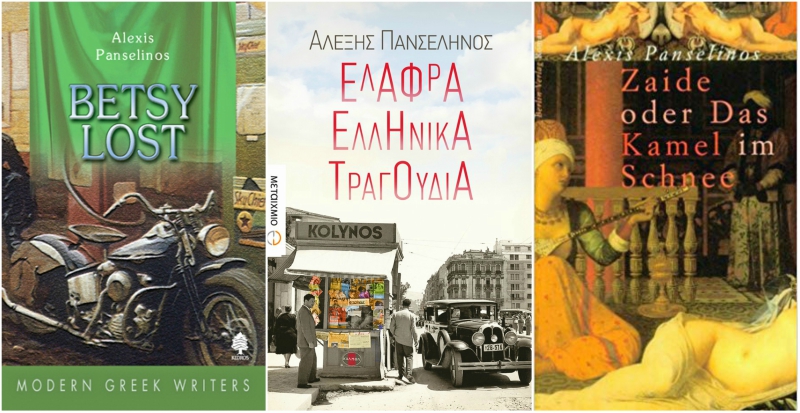

His first book, a collection of four stories, appeared in 1982. In 1986 he published his first novel, The Great Procession, which obtained a national award. In 1997 he was the Greek candidate for the European Literary Award (Aristeion) with his third novel, Zaida or the Camel in the Snow In 2012 he was awarded by ‘Diavazo’ Magazine for his novel The Dark Inscriptions in 2012.

Several of his books (The Great Procession, Zaida or The Camel in the Snow, The Dark Inscriptions and Betsy Lost) have been translated into other languages including Italian, German, English and Polish. He has also translated novels from English and German.

Alexis Panselinos spoke* to “Greek News Agenda” about the influence of his parents in his decision to become a writer, the characters of his books, the economic crisis, as well as about his latest book Light Greek Songs.

You are an awarded writer and your work has been highly appreciated. What influenced your decision to become a writer? How much did the fact that your father, Asimakis Panselinos, was also a famous writer contribute to this decision?

I was born at a time when people were reading books, went to the theatre and cinema. We had a library in our home and the presents I received on festive occasions were mainly books. I was enthralled by literature and I began writing in my early teens. Both my parents were writers. At home, we’d have poets, artists, and novelists coming and going all the time, the tone was vividly artistic in every regard, so I had the opportunity to grow and develop my flair for writing from an early age. My early works were written with the conviction that as an adult this -writing- would be my main occupation and my life.

How do you choose the characters in your books? To what degree do their toughness and imperfection inspire you and what room do you leave in your works for the optimism of life?

My approach is realistic. My writing may play fantasy games, but I use it to intensify the clarity of the view on people and life. None of my heroes is tough per se, people are complex and toughness often covers up their fears and weakness. People are imperfect, and this makes us human. Our weaknesses, our mistakes, are interwoven with our dreams, with love, with the fear of death, with our ideals which, even when betrayed by our weakness, remain within us like a festering, open wound. Life itself is an optimistic situation. As long as one is alive, he fights, hopes, dreams; and that’s optimism.

Do you like changing your narrative style, experimenting with writing forms?

Do you like changing your narrative style, experimenting with writing forms?

I actually don’t like repeating myself, and I strive for different forms with every book. This is also the case because the choice of subject every time entails a different form by itself. The subject determines the form, the subject has its own requirements and it is served more efficiently by a particular technique, a different style. My personal obsessions may not change, but there are a thousand different ways of looking at them – and that’s what I do. All in all, I write the same book over again, and a sensitive reader can grasp this.

Today, many Greeks are suffering on account of the economic crisis. Do you believe that art, and literature in particular, has been positively or negatively affected?

The economic crisis we are going through is not something new. We have experienced it in the past, and I could go as far as saying that it has never gone away. In one way or another, Greek society, as well as many others around the world, is experiencing a crisis. History, communities, people and countries, are in a state of permanent crisis. History is the process and the successive mutations of this crisis. And literature has a double role – on one hand to depict it, and on the other hand by way of metaphor to turn it into consolation, a breath of hope and optimism for the future – because the beauty of life and the world still exist to support us even in the most distressed, and the most difficult circumstances. The country has lived through a decade of foreign Occupation and Civil War, and people who lived through these horrendous times have managed to create and hope, to fight and overcome the disaster. I cannot see why the current crisis will not be overcome.

You come from Lesvos. What is the image you have of the island following the refugee wave that has overwhelmed it in recent years?

With Lesvos, I have a distant relationship, but also one of deep love. I was not born there, but in Athens – in the heart of the city as a matter of fact. I have visited Lesvos only a few times and always as a tourist rather than as a returning native. I visited the island last year in the spring, at a time when the Moria refugee camp was already in operation: refugees and migrants had already been moved from the harbor area where acute problems for the inhabitants of Lesvos had been created, but the sight of the camp in Moria, with its high metal fencing topped with coils of razor-barbed-wire, as well as the concrete shelters where these people were living in made my heart freeze. It seems that the situation has gotten much worse since then. It is both sad and outrageous.

Your last book, Light Greek Songs, refers to the 1950-1953 period, a time that was marked by the execution of Nikos Beloyannis, with the wounds of the civil war still open, but also a time when there was hope of rebuilding the country, when there was need for security and carefreeness. What prompted you to choose to depict, and very successfully too, this particular era?

In my book Light Greek Songs I endeavor to look at the history of the country as a whole, from the end of the Civil War to the present. I am concerned with the construction of a post-war and post-civil war country, in the form it took under the governance of the winning side, preserving the acrimony, rancor and spite, along with the destructive maladies that have brought us to the current crisis, which aside from economic is also moral and political. So the nostalgic gaze upon the Athens of my childhood is tinged by the awareness of the distorted evolution of our society which was based on division, preventing us in the process from realizing that we are part of the same society and that our actions concern us as a whole and not only as individuals. The so-called “light” popular songs of that era were the people’s call for beauty, optimism, peace and progress. My novel is not an ethography of the ’50s; it is an anatomy of the contemporary deadlock, the bankruptcy and discrediting of political thought and action, of intolerance and the absence of goals. The reader should see through the lines of this light-hearted, distant narration – as one should through those cheerful melodies, the buoyant rhythms and the often naïve lyrics of those 50s songs, hear the beat of peoples’ hopes, who throughout the 1940’s had been bleeding and experiencing darkness and despair.

What message would you like to convey to writers of the younger generation?

A writer must stand courageously in front of the mirror that is his art. To see his face clearly, to reject flattering disguises and to recognize in his image the image of the society that surrounds him. He must also not forget that art has its rules and that a writer’s basic tool is language.

*Interview by Marianna Varvarrigou

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Writer Vangelis Raptopoulos on “The man who burned down Greece”; Kostas Katsoularis on Books as Living Organisms and Book Readers as a Species Facing Extinction; Nikos Mandis on Fiction, Labyrinths and Athens as the Main Protagonist

N.M.