His writing, his impressions of Greece and his Greek intellectual circle

The purpose of this short note is to summarize Patrick Leigh Fermor’s perceptions of Greece and its people. A natural charmer, he made friends from all strands of life. He traveled with the nomad Saracatsans, he fought side by side with Cretan shepherds and drunk in Athenian taverns in the company of some of the most prominent literary figures of the time. The richness of his travel writing is due as much to the description of the country’s natural landscape as to the discovery of its human landscape.

Patrick Leigh Fermor (Paddy for friends and funs or Mihali for the Greek villagers) was born in London in 1915. On December 9th 1933 he boarded the Dutch steamer Stadhouder Willem. After a year and twenty-one days, having walked through Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, he reached Constantinople at New Year 1935. His walk would result many years later in the trilogy A time of Gifts – On Foot to Constantinople: From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube (1977), Between Woods and Water (1986) and, posthumously, The Broken Road (2013).

The man who Freya Stark described as “a Hellenistic lesser sea-god of a rather low period” first set foot in Greece in 1934 on his way to Mount Athos. After that and for the seventy years that followed he took part with the royalist troops in the venizelist rebellion of 1935, he met with the Sarakatsans in Macedonia, he fought in the front of Albania and in the Battle of Crete and travelled across Mani and Northern Greece. From the mid-60s he lived with his wife Joan in Kardamyli.

Perceptions of Greece

The Peasants…

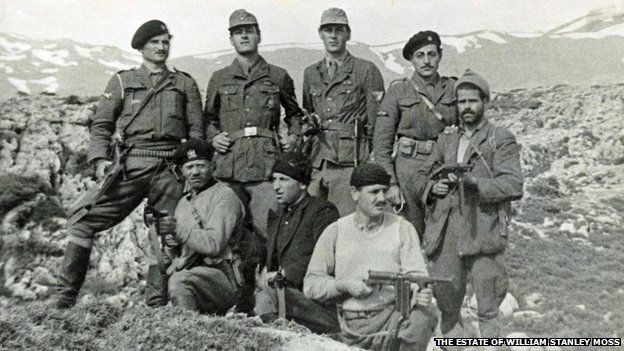

The Greece PLF most knew was the Greece of Mountains and shepherds. That was one of his assets during the war years; yet, it was a source of conflict with other British Intelligence Officers who had a formal education in classical studies. One of those was Christopher Woodhouse. In Leigh Fermor’s own words “This was always the real root of the friction, a constant jealous, unarmed struggle as to who had the greater proprietory rights to Greece”.

During his travels, his is trying to associate the ordinary people he meets with their immediate landscape and with their history. Although Crete has a central place in PLF’s biography and it is the place where his war hero legend was created, Leigh Fermor did not write extensively about the island. Michael Llewellyn Smith observes that PLF’s impressions of Crete derive from his wartime view of the generosity and bravery, the leventia, of the Cretans. He does not explore the history, architecture and folklore of the place as he does in Mani and Roumeli, his books about mainland Greece. Already during this first sojourn in Crete he affirmed that “Cretans were like the Greeks, only more so”. Still, in the preface of Mani Leigh Fermor writes that “the aim of this book is to situate and describe present-day Greeks of the mountains and the islands in relationship to their habitat and their history; to seek them out in those regions where bad communications and remoteness have left this ancient relationship, comparatively speaking, undisturbed”. In Roumeli, he tries to distinguish between the Greek and the Roman, what is known as his “Helleno-Romaic Dilemma”. It summarizes the two self-images of Greek culture, the tension between them constituting the unique dialectic of the Modern Greek identity, as M. Herzfeld explains. In Kardamyli, where Paddy and Joan were eventually to settle, he noted how conscious the people were of the antiquity of their village.

In her review of Roumeli, Mani and Words of Mercury, the classicist Mary Beard has a different point of view.She argues that when PLF is describing the social interactions of the Greek peasants using Homeric terms, what he is really doing is adopting the assumptions of primitivism and historical continuity of 20th centrury romantic Hellenism. In any case, Beard continues, that “when you see through all the nonsense about Hellenic continuity, there is, underneath, a much more nuanced account of the ambivalences of modern Greece, its people and its myths”.

…and the intellectuals

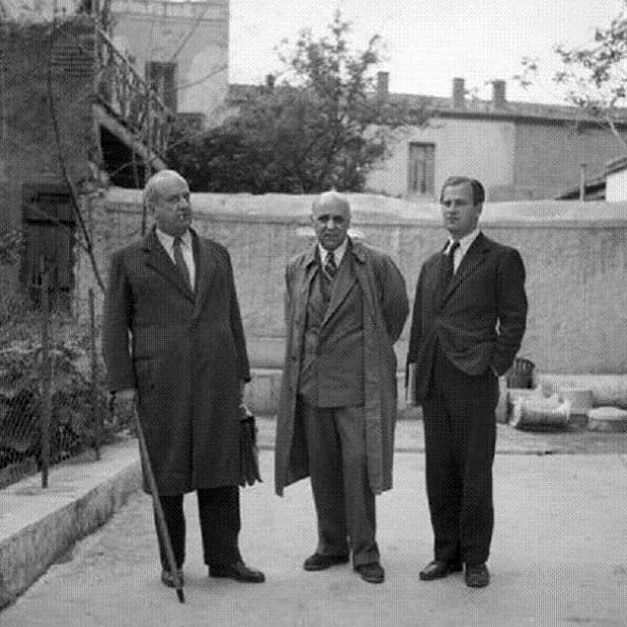

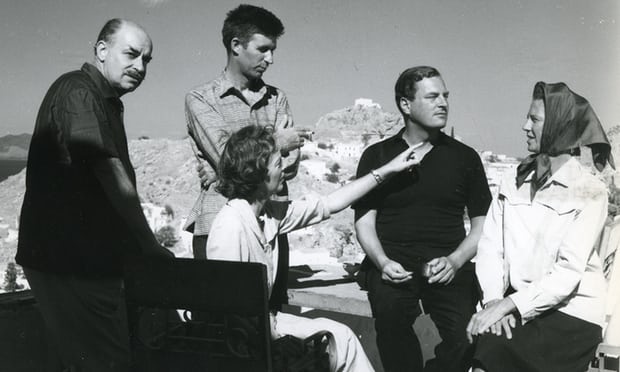

His encounter with the representatives of the Greek letters occurred in the mid ‘40s during his short term as an employee of the British Institute (now British Council). Before the war, another “legendary” group of friends was formed in Athens consisting of Katsimbalis, Ghika, Seferis and Henry Miller. In the mid-40s, Fermor enters this circle of Katsimbalis, Ghikas and Seferis which is amplified by the British intellectuals who lived in Athens.

According to Artemis Cooper, one of Fermor’s closest friends at this time was George Katsimbalis. PLF remembered him as “a brilliant raconteur, of living stories rather than rehearsed party pieces. Llewellyn Smith characterizes this period (1945-1950) as the Age of Gold british-hellenic artistic and literary collaboration. The center of this collaboration was the the Anglo-Greek Review supported by the British Institute. As with the case of Henry Miller, who dedicated his Greek travelogue -The Colossus of Maroussi– to Katsimbalis, Partrick Leigh Fermor was equally impressed by this boisterous erudite. Avi Sharon claims that what appealed most to both Miller and PLF was the Katsimbalistic ideal of a Greece “free of the usual classical clichés, a primitive landscape and light that could serve as the salutary antithesis of a twilit Europe”. For PLF he was also the embodiment of his Helleno-Romaic Dilemma (a wrestling match between Plato and Kolokotrones).

Witness to PLF’s long lasting friendship with Nikos Hatzikyriakos-Gkika is the extensive correspondence between the two men. Despite their differences of character, they were united by their erudition and vast knowledge of arts. It is well known that Fermor stayed for two years in Gkika’s house in Hydra where he wrote the biggest part of Mani and translated the Cretan Runner.

In the person of Seferis, PLF found a kind of mentor and try to tame his tendency of Penelope-izing. They both recorded their lives extensively and wrote to each other until Seferis’ death.

The travel writer

The nowadays underestimated genre of travel writing is indebted to PLF for he has adorned it with reflections from his wide reading and playful attitude. Kevin Volans describes Leigh Fermor’s writing as “full of baroque fioritura” most evident in his descriptions. His narrative is full of digressions. The most quoted one is that at the beginning of his book on Mani where he is listing the variety of peoples one can find in Greece. The list goes on for two pages. Colin Thubron notes that “despite the richness of his prose he forged an illusion of intimacy with his readers”.

The Franks of the Morea, the Byzantines of Mistra, the Venetians and Genoese and Pisans of the archipelago, the boys kidnapped for janissaries and the girls for harems, the Catalan bands [..] the admirals of Hydra, the Panariots of the Sublime Porte, the prices and boyars of Moldowallachia [..] the Cretan fellaheen of Luxor, the Elasites […] the Chinese tea-pedlar of Kolonaki.

Robert F. Worth affirms that the richness of prose is also due to the gap between the experience and its narration. Leigh Fermor begun to write the first book about his journey, “A Time of Gifts” in the 1970s. As a result, the travel narratives are a kind of palimpsest in which his younger and older selves exist in counterpoint.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was a person easy to like. He shaped modern views of Greece and at the same time, as film-maker Michael Powell put it he captured the love and imagination of the Greeks as no other foreigner except Lord Byron has done.

Read more via Greek News Agenda:Ghika – Craxton – Leigh Fermor: Charmed lives in Greece;UK Ambassador to Greece John Kittmer’s farewell; Reading Greece | An englishwoman in Evia: Publisher Denise Harvey on her love for Greek literature and culture; Henry Miller: On friendship, light and a paradise lost in Greece;

Lina Syriopoulou

TAGS: ARTS | GLOBAL GREEKS | HERITAGE | LITERATURE & BOOKS