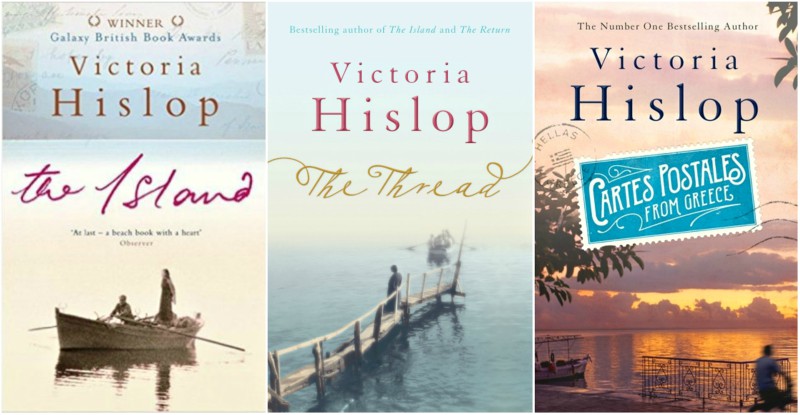

The International Tourism Exhibition WTM 2018 took place at ExCel, London for three consecutive days (5-7 November 2018). The Greek National Tourism Organisation (GNTO)’s surprise guest of was best-selling author Victoria Hislop, who has written several books based in Greece including the best-selling novel The Island, which has also been adapted for Greek television with huge success.

A journalist and an important contemporary literary figure that has forged close ties to Greece and its people over the years, Hislop addressed the audience at the GNTO Press Conference at WTM and revealed that she is hoping to work with the tourist board to transform some of her short stories into films that will “introduce people to a different side of Greece”.

Her short stories, which are due to be filmed next year and should be screened in 2020, areset off the beaten track in locations such as monasteries and small, little-known villages. “They will take people below the surface and introduce them to another side of Greece, away from the seaside resorts because it would be a shame to visit Greece and see only the beach,” said Hislop.

Victoria also spoke to the Press & Communications Office at the Embassy of Greece in London about the unique love that Greece has inspired to her, about her experiences from Greece as well as about Greece as a source of inspiration for her work of fiction.

Where does your passion for Greece stem from? Do you have Greek roots?

This combines well with the next question too! My first visit was when I was seventeen years old – I went to Athens with my mother and sister and I fell in love with the country immediately. It was unquestionably a keravnovolos erotas (love at first sight). From that year on, I visited every year, more and more so with the passing decades. That first trip really showed the contrasts of Greece to me. Athens was so different in 1977! I enjoyed the chaos (don’t forget this was pre-metro system, and my memory is that few signs were in anything other than Greek), the ancient culture, and unfamiliar food (in those days feta and watermelon were not available in the UK!). Then Paros: it was my first experience of going on a ferry and at that time there was no airport, so mass tourism had not really arrived. Everything was enchanting – swimming in the Aegean for the first time, finding minute white shells, eating fresh fish, feeling real heat.

I don’t have any Greek roots – but even back then, I had a sense of having arrived somewhere that I “belonged”. It was a warm feeling and I still get it every time I land in Greece.

How closely have you come to the everyday life of Greeks? And how do they usually perceive you? Have you ever felt being treated as “one of us” or as a foreigner who just visits their country and is fascinated by it?

I think I get as close to everyday life as anyone could who is not a full time resident – or who does not have Greek blood. I usually spend several months every year in Crete and most of my friends there are local people so I do all the things they do and go to all the places they go, and dance with them at glentia (fairs) and this is when I feel as though I have become an insider. I regard many friends there as my family, and they treat me like one of their own.

Some Greeks are mystified by my love of their country. They think I only see it through rose tinted lenses. And to some extent they are right – because I have the privilege of coming and going. London is my other “home” and putting the chaos of the Brexit situation aside, the UK during my life has been an organised, growing and thriving country – and London has become one of the greatest cities in the world. So yes, I know I am privileged to be able to come and go and to work in both places.

How has your love for Greece evolved over the years? Any peaks, fluctuations, setbacks or frustration?

Over my forty years of visiting, I have learned a lot about how things work in Greece and I appreciate that this is a country with its own modus operandi. When we were filming the television series of To nisi (The Island), I spent almost eighteen months there, on the set and of course there were some peaks and troughs then. This was a creative project but also a commercial one so inevitably there were moments of tension – but ultimately the best results we could have hoped for.

What led you to start learning the Greek language? Moreover, how and to what extent has it helped you gain a better insight into the country and its people? What is the most representative Greek word for you?

I began largely because I wanted to communicate with a particular person in Greece who was 80 years old at the time and did not speak English. He was Manoli Foundoulakis who had been a leprosy sufferer and we became close friends – he was an amazing person but I realised that I would only ever truly appreciate his humour and wisdom if I learned to speak the same language – having someone close by to translate is not the same. And given how much time I was spending in Greece researching and promoting my books – it was impossible and unsatisfying to do everything in English. I think you never get below the surface without the language. Also – of course – I have a house in Crete (ten years now) and there are so many practical things to deal with too – I need to explain things to a plumber and an electrician sometimes and that’s a whole other set of words!

I learned at the Hellenic Centre in London at the beginning – with an amazing teacher called Thomas Vogiatzis – who has a real gift for teaching. In my first lesson I told him that I had a target: to give a speech in Greece within three months and to do a radio interview. Thomas was undaunted – and because of him I achieved it.

Most representative word -and my favourite- is zaharoplastio – I don’t even have a sweet tooth! But it is such an exciting set of syllables, such beautiful sounds and a really seductive word. The English equivalent “cake shop” doesn’t really have the same ring, does it?

Victoria Hislop with Greek Minister of Tourism Elena Kountoura

Victoria Hislop with Greek Minister of Tourism Elena Kountoura

You have also visited and written about Mediterranean countries other than Greece. What similarities and differences have you detected?

There are definite similarities with Spain – but even these are very different countries. Perhaps on a slightly negative note, Spain has severe economic difficulties, but there is a much greater respect towards property and the environment that I don’t always see in Greece. In Spain you don’t get the same impression of anger and sometimes desperation that I sometimes detect in parts of Athens, for example.

In your mind, is there such a thing as “a Greek way of living”? If yes, what are the main components of this way of living?

I have never met anyone in Greece who lives to work. Greeks in Greece work to live. It’s a very different lifestyle. I would say this is the opposite in London, where many people are driven by career or a love of what they do and make this a priority. On average, most people I know in London work at least ten hours a day, maybe even twelve. This is totally standard, especially if you are working for yourself, running a business or ambitious. Apart from a few creative people, I don’t know anyone in Greece who works such long hours. I don’t make any criticisms of this, it’s simply an observation. And along with this, in the UK (London especially) people are compelled to work long hours out of necessity to pay a mortgage or their rent, which can easily take 70-80% of their earnings. So I think this allows a more relaxed lifestyle in Greece too – if you are paying 200 euros a month in Athens for your rent (as opposed to £1000 a month in London), you perhaps don’t have to be so driven. So many people I know in Greece have been given property by their parents – this is unheard of in the UK! So… even if many Greeks don’t appreciate it, their lifestyle can be quite a nice one.

Family is a bigger focus too – perhaps this defines life for many Greeks because they live closer to their family in many cases. And approaches to children – there is a hugely different approach in Greece. The Greek way of living is much more child-focussed. The very fact that children have long sleeps in the day and stay up all evening creates a very different ethos. I think it’s great in the summer, but I know I couldn’t have done it all year when my children were small. Our children happily went to bed at 7 in the evening.

I was with them for twelve hours a day, 7 until 7 and then had part of the day that was absolutely my own. This was when I read, went to plays, films, concerts and had totally adult conversation and talked about things other than children! I would never have written any of my books if my children had gone to bed at the same time as me – and to be honest to sustain any kind of life of the intellect, I think it’s crucial for adults to have some time for themselves.

Finally on this one. The UK style is to teach our children to be independent, and many of us send our children off at the age of 18 (often to South America or Australia) to learn independence and survival. We don’t try to keep them close. It’s painful when they leave the nest but we want them to be strong, to spread their wings and fly.

Apart from touring through the Greek islands, you have also taken your readers on a journey to Thessaloniki, the second largest city of Greece (The Thread, 2011). What do you find particularly inspiring about Thessaloniki and its history? Do you believe that Greece’s mainland is undeservingly underestimated from a tourist’s perspective?

Thessaloniki is a fantastic city. I am very fond of it for so many reasons and spent a huge amount of time there researching The Thread. It has so many layers of history and perhaps most importantly a very successfully multicultural past, with its sizeable Moslem and Jewish populations. On an aesthetic level, it is in a very beautiful setting and to be in a buzzing and thriving city, and yet be able to sit overlooking the sea, is a huge pleasure. The huge student population adds a great deal to the energy of the city – I think that is a key ingredient too. I was recently given an Honorary Doctorate (at the same time as the Mayor, Yiannis Boutaris) by Sheffield University City College, so Thessaloniki has become even more important to me.

I think the majority of holidaymakers think of the islands rather than the mainland in the summer. And the islands are very beautiful, certainly. However, there are amazing landscapes and destinations that get missed – the Peloponnese for example is an incredibly beautiful area in itself but quite often people just make for the beach and stay there without seeing the interior. So sometimes I don’t think it’s underestimation exactly, but just not really knowing a place is there and being directed to the seaside resorts. And Meteora, another example, a truly spectacular landscape – but because it’s not close to the sea, I don’t know a single Brit who has been there.

In your latest novel Cartes Postales from Greece you cooperated with your photographer friend Alexandros Kakolyris who accompanied you to a tour in Greece. How did you come up with the idea of creating a book based on these photos?

For all my novels, I have taken thousands of photographs, put them on my walls and used them as inspiration. So the idea to include photography actually in a book seemed a very natural and obvious one. The development of the stories simultaneously with the taking of the photos, however, was a crucial factor. I didn’t want to send a photographer off once I knew the plot in order to take something after the event – so a photograph for example, of the man on the mountaintop in Meteora was absolutely ‘live’ as I thought up the story – the illustrations for this book are really integral, not an after-thought. Alexandros agreed to travel with me and in many cases saw something that I did not – and pointed me in the direction of a story through his images.

In an interview that you gave for ‘Greece Is’ you have said that “We live in a world where we’re seeing things all the time, and a lot of the newspapers, magazines as well as non-fiction books have masses of pictures. Why should fiction be any different?” Do you think pictures could be an important part of adults’ fiction books?

In an interview that you gave for ‘Greece Is’ you have said that “We live in a world where we’re seeing things all the time, and a lot of the newspapers, magazines as well as non-fiction books have masses of pictures. Why should fiction be any different?” Do you think pictures could be an important part of adults’ fiction books?

I see no reason why not! I think words and pictures are a very natural combination! Photos can enhance a story without taking away from the imagination.

After your experience of writing Cartes Postales from Greece, would you attempt to write another book using the same technique?

Definitely. It was a huge success in the UK and many other countries and we have already begun work on a sequel to Cartes Postales.

In the introduction of the same book, you mention that the book’s “pages tell the story of a man’s odyssey through Greece; moving, surprising and sometimes dark.” Is every journey to Greece an odyssey, and in what sense? What are the dark sides of such a journey?

On every journey to Greece there is a surprise for me, something unexpected that I really did not know or imagine. Even after literally hundreds and hundreds of trips and days spent there, there is always something new to learn.

Dark sides… Perhaps it is true that I have seen things through rose tinted lenses and gradually more light gets in.

Anthony Horowitz of The Telegraph wrote in an article that your books can turn someone into a “Hellenophile”. How do you perceive this term and how does Horowitz’s remark make you feel?

That’s a great word – and I agree with him up to a point. I do perhaps make people love Greece, but more importantly I hope that I help people understand it too. For example, with The Thread, which traces the 20th century history of the country, many of my British readers really had no idea about the German occupation of Greece nor how harsh it had been. Nor about the civil war. So that, for me, was important to communicate: that Greece has endured extraordinary periods of hardship – much more than the UK – and this has had an impact on the present day situation.

How will your “love affair” with Greece continue in the near future? What to expect?

I think it will continue. My dream is to get a Greek passport – so my passion for the country definitely continues! I have just delivered a new novel (set in Greece of course) to my British publisher which will come out in English in May. And we are hoping to start filming some adaptations of my short stories next year in Crete – so my work in Greece goes on!

Not to mention my affection for Greek friends and “family” who are always there waiting for me. They are at the centre of my love for Greece.

Read also via Reading Greece: Richard Clogg: “I am continually struck by the ignorance of the recent history of Greece that exists in the UK”; Sharon Gerstel: “Byzantine History opened my eyes to a culture that has long been marginalized in our studies”; Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek; An Englishwoman in Evia: Publisher Denise Harvey on her love for Greek literature and culture