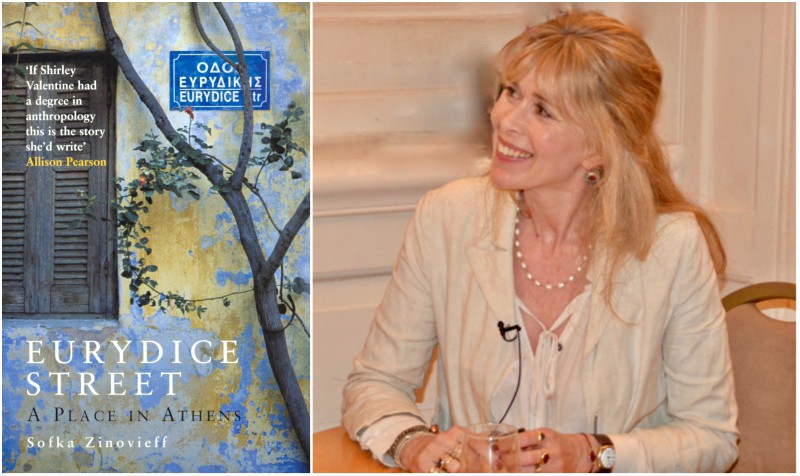

What does it mean to be Greek? What connects Greek and British people? How does the ancient Greek heritage weigh on contemporary Greeks? These are some of the questions that the acclaimed British author, Sofka Zinovieff, attempts to answer in her autobiographical book Eurydice Street: A place in Athens (2004) and the fiction books The House on Paradise Street (2012) and Putney (2018), which feature Anglo-Greek families based in Athens or London.

On 2 April, Mrs Zinovieff gave a captivating speech on those three books at the Hellenic Centre in London. The event was organised by the Anglo-Hellenic League and raised £525 for the Greek disability charity, ELEPAP.

In an interview with the Press & Communications Office at the Embassy of Greece in London, Mrs Zinovieff talked about Greek language, history and politics, the complex relationship between Greece and Britain; and everyday life in Athens, based on her personal observations and research.

You have lived and traveled in Greece, have studied and written about Greek culture and history and are married to a Greek man. In your autobiographical book, Eurydice Street, you recount your efforts to acquire the Greek citizenship and “become” Greek. In your opinion, what does it mean to be Greek?

I am fascinated by Greece and have loved the country since I was an anthropology student in the 1980s. Acquiring citizenship was more symbolic than practical. It represented my commitment to an ideal, rather in the way you commit to a person when you marry them. I see my relationship to Greece as a lifelong endeavour, with all the ups and downs that anyone has with the country they choose to make their own. However, it is certainly based on love. As to what it means to be Greek – that is something I’ve been trying to work out in my books over many years! A short answer would be impossible.

In the same book you recall the language games that you used to play with your daughters, translating Greek expressions literally into English, i.e. “You are going to eat wood”. Your Greek is excellent. What are the benefits of learning Modern Greek?

Greek is a rich and marvellous language and another lifelong endeavour for me. I never learned it officially – I didn’t study it at university – so my written Greek is not as good as I’d like. Nevertheless, I love speaking it and it’s what I talk at home with my husband, Vassilis and with my Greek friends. I would recommend anyone to learn Greek, even though it is not one of those languages classified as ‘easy’. I’m so happy my daughters both grew up bilingual, with all the benefits that brings in terms of broadening horizons and versatility of thought.

In your words, “you dig any little hole in Athens and you’re immediately inside the ancient world”. What is the connection between ancient and Modern Greece? How important is the ancient past for contemporary Greeks and Brits who study Greece?

When I was a youthful anthropology student I was rather annoyed by the fixation on ancient Greece – often by foreigners who seemed to value the long-lost past over the present. Now, I think the interaction between the present and the past is something we can’t escape. We should examine it and in Greece, the ancient past is very much part of identity and above all, the physical surroundings. The old chestnut about whether modern Greeks are descended from the ancients in terms of DNA is irrelevant to me. I believe what my late father-in-law used to say: modern Greeks walk along the same paths and in the same landscapes as the ancients did. Even without the language, the myths and the ruins, this has a huge impact and is a powerful connection.

Describing Greeks’ attitude towards Greece you have written: “If Greeks have a passionate pride and love for their country, they also hold feelings of shame, pity and disappointment”. How would you explain this ambivalence?

Describing Greeks’ attitude towards Greece you have written: “If Greeks have a passionate pride and love for their country, they also hold feelings of shame, pity and disappointment”. How would you explain this ambivalence?

I’d say it’s the result of the complexities of Greece’s history. Greeks managed to keep their ‘Greekness’ alive during all the years of Ottoman rule. Passionate pride was encouraged by the battle for independence and by the wave of nationalism sweeping across Europe through the nineteenth century. Having become a nation state, Greece then found itself repeatedly at the mercy of stronger nations, which I think provoked insecurities from not being able to determine its own future. In addition, the state has often shown itself to be dysfunctional and has perpetuated the lack of trust by individuals in anything other than their own efforts and connections.

I wonder whether the burden of ancient Greece might not also play a part in these mixed feelings. I think of Seferis’ reference in Mythistorema to waking with the overwhelming weight of a marble head in his hands and how it has been hard to live up to the vast significance of history.

Sometimes Greece reminds me of a family which has many wonderful qualities, but also has problems: its members fight and feud but they don’t appreciate outsiders criticising them and can unite in the face of external opposition.

In the fictional work, The House on Paradise Street, Maud, an English woman -married to a Greek man- tries to fit into Greek society, but feels that she will always be a xeni (foreigner), “an awkward hybrid who belonged nowhere”. What are the perks of being an outsider, of belonging nowhere?

I have felt an outsider ever since I was a child in England, so it’s something I have built into my character already. I find being an outsider in Greece an excellent way of living – I’m rather a different person to Maud! I’m enough of an insider in Greece to have friends, family and a way of life I love, but I don’t need to engage with some of the more painful aspects of being Greek and can step back from the fray.

The House on Paradise Street is a story of a family riven by the Greek Civil War. Do you think that divisions created by the Greek Civil War still play out in Greek politics? To what extent does political orientation define Greeks?

I used to think that Greeks were very different to the British in their passionate political beliefs and the divisions between right and left that were played out in such a deadly and destructive way during the Civil War. Now, with the bizarre and humiliating mess of Brexit, I’ve changed my mind. We can see that families and friends are divided in Britain and that instead of discussing differences of opinions, people often merely express hatred.

Having said that, I do think that the Greek Civil War was a particularly painful episode and that the scars have still not healed properly. It has led to people identifying very strongly with their political orientation – often that of their families.

In the same book, you also refer to the relationship between Britain and Greece, highlighting both heroic events of Greek-British collaboration, such as the blowing up of Gorgopotamos bridge, as well as dark moments such as the Dekemvriana in 1944. How deeply have the relations between Britain and Greece affected Greek history and society?

It was so interesting for me to research the complex relationship between Greece and Britain for The House on Paradise Street. In Greece, I spoke to people on both sides of the Civil War and I created two divided sisters – Antigone and Alexandra, who represent these allegiances. It was shocking to hear the stories from women who had ‘gone to the mountains’ in the resistance against the Nazi occupation – not just what they had gone through then, but how they were arrested, executed and persecuted afterwards by the right-wing regime that was supported by the British and the Americans. In the eyes of these women (on whom I based Antigone), the British were traitors who fought and killed their erstwhile allies on the streets of Athens in the Dekemvriana. To those who feared the rise of communism (like Alexandra), the British were quite right to have helped Greece escape Stalin’s grasp and prevented it ending up like its northern communist neighbours.

These are incredibly important elements in Greek history and while they underlie so much in Greece, I’ve been surprised by how little known they are in Britain.

“Dekemvriana“: Paratroops from 5th (Scots) Parachute Battalion, 2nd Parachute Brigade, take cover on a street corner in Athens during operations against members of ELAS, 6 December 1944. (Morris (Lt), No 2 Army Film & Photographic Unit. Photo NA 20515 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums / Wikimedia Commons)

“Dekemvriana“: Paratroops from 5th (Scots) Parachute Battalion, 2nd Parachute Brigade, take cover on a street corner in Athens during operations against members of ELAS, 6 December 1944. (Morris (Lt), No 2 Army Film & Photographic Unit. Photo NA 20515 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums / Wikimedia Commons)

Having written about your daughters’ experience in Greek school, you note the value that Greeks place on education. What is the role of education in defining Greek identity?

Education is held in utmost esteem in Greece. It has been the way of improving life chances for countless Greeks who might have begun their lives in humble circumstances but have reached the highest offices and made their fortunes through becoming educated. In Britain, education is appreciated but it is complicated by the class system and the way that private schools have dominated the education of the ruling classes.

Greek education is far from ideal – the fact that state schools are supplemented to a dramatic degree by parents paying for private lessons for their children means that it is actually a rather strange hybrid system. However, it is always remarkable to me how even the most remote villager with few means will do whatever they can to get the very best education for their children. I don’t think it’s like that in Britain.

When describing Greek everyday life you mention religious rituals, followed in Greece even by Greeks who do not believe in God. What is the role of religion in Greece?

We moved back to live in Greece from Rome, so I inevitably compared Italian Catholics with Greek Orthodox. There seemed to me to be an ease with the religion in Greece, where you can be relaxed in your relationship to the Church and not wracked with guilt or questions of Faith. Religion has been a fundamental element in identity and is embedded in Greek life, so an individual will still probably be baptised, married and buried by a priest, even if she or he is not a believer. Orthodoxy is a constant and a bedrock, even if, like every religion, it has its own problems and contradictions and could probably do with being separated from the state a bit more.

Eurydice Street is an affectionate, but not rose-tinted, picture of Greek society before the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, written during a rather affluent period. How would you describe Greece today, after an 8-year-long economic recession and the influx of a large number of refugees?

Eurydice Street would surely be a very different picture of Athens if I wrote it today. 2004 was a high point in recent times and there was a sense of optimism that has evaporated over these recent difficult years of the economic crisis and the tragedy of refugees seeking refuge in a place not fully equipped to cope. It has been a traumatic time in Greece, but I have a strong belief in the resilience of Greeks who have been through so much over the last century. If they can bounce back after wars, occupations and dictatorships, they can surely do it again now. The first signs of things improving are beginning.

You describe Athens as exciting and erotic. “People looked into your face as you walked down the street, making a visual contact, however brief, that was not found in northern European cities.” What are your favorite places in Athens? How could a traveler, visiting Athens, get the feel of Greek everyday life?

I do believe that Athens is an erotic city, though of course it’s down to the people, not the place! And perhaps the term sensual would also apply. I like the engagement that goes on between people that you don’t find in northern Europe.

I’d say the best way of getting a feel of everyday life is to talk to people and to walk around. The neighbourhood is such a significant aspect of living in Greece, so hanging around almost any neighbourhood square, checking out shops, cafes and the local church is an obvious way of getting some insight. I also believe that going to the area around the central markets and Omonoia gives a sense of Athenian openness – both to incomers from the villages and islands but also to foreigners and refugees. Greeks often have strong links to their local origins but wide horizons to the rest of the world.

Omonoia Square, June 2016 (George Voudouris/Wikimedia Commons)

Omonoia Square, June 2016 (George Voudouris/Wikimedia Commons)

In your latest book, Putney, your interest moves from intercultural to intergenerational differences, as you explore the changing attitudes towards consent and child sexual abuse since the 1970s. How has your understanding of different cultures helped you engage with different perspectives on such a sensitive issue?

Putney has been described as ‘A Lolita for the era of #MeToo’ and it describes a 13-year-old girl’s ‘love affair’ with an older man in the ’70s and the fall-out decades later when she starts to realise it was actually grooming and abuse. I am interested in the pendulum swing between attitudes during my youth and those in the present day when arrests for historical child sexual abuse make up a large section of police work. We see things differently now.

I was definitely helped in analysing this by having studied social anthropology as it gave me the ability to stand back and realise that everything is relative and cultural. There is no ‘normal’ in our attitudes towards sexuality, which vary hugely across societies and across time.

Although this novel is set mostly in London, the family at its centre is Anglo-Greek and there are many parts which take place in Greece. It seems almost impossible to keep Greece out of my writing, even with a title like Putney!

What are you working on at the moment? What are your plans for the future?

I’m working on another novel now, as well as some short stories. I won’t say more except to add that I couldn’t keep Greece out of this one either!

My plans for the future are to be based in Athens but with plenty of time in London, where our two daughters live. I’m hoping that a balance between the two countries will be the ideal way of life.

About Sofka Zinovieff

Sofka Zinovieff was born in London, has Russian ancestry and is deeply attached to Greece. After studying social anthropology at Cambridge, she wrote her PhD thesis on Modern Greek identity and tourism and then lived in Moscow and Rome, working as a freelance journalist for British newspapers and magazines such as The Telegraph, The Times Literary Supplement and The Independent.

She is the author of five books, including a memoir, Eurydice Street: A Place in Athens, (included in New York Times’ ‘100 Notable Books’ 2005). Her first novel, The House on Paradise Street explored the Athenian riots of 2008 and the Greek Civil War. Putney is her latest novel and has an Anglo-Greek family at its heart. A ‘Best Book of 2018’ in The Observer, The Spectator and The New Statesman, it was described by the Financial Times as ‘an important addition to an urgent, current conversation’.

Sofka is married, has two daughters and lives mostly in Athens.

For more information, see Sofka’s website www.sofkazinovieff.com

Read also via Greek News Agenda: Victoria Hislop: I want to get my short stories turned into short films to introduce people to another side of Greece!; Hilary Roberts on German and British Photography in Greece 1940-1945; Professor Gonda Van Steen on her lifelong fascination with all things Greek; An Englishwoman in Evia: Publisher Denise Harvey on her love for Greek literature and culture; Richard Clogg: “I am continually struck by the ignorance of the recent history of Greece that exists in the UK”

N.M.